We Are Not Alone

Will “Johnny B. Goode” play as well on other planets?

One of the most profound experiences of my life was attending a lecture by astrophysicist Dr. Stephen Hawking at a trade show in the 1990s. Hawking, who passed away last year, was one of the greatest scientists of all time — right up there with Einstein — despite suffering from ALS, a debilitating condition that caused him to be almost completely paralyzed for much of his life.

There he sat on stage, his broken body slumped over in a wheelchair, painstakingly using his pinky (one of the few parts of his body that he could still move at that time … though he was also able to manage a wry smile every now and then) to advance through an array of PowerPoint slides, delivering revelation after revelation to a spellbound audience. There were thousands of us in attendance, yet you could literally hear a pin drop, so focused were we all on what Hawking had to “say,” courtesy of his laptop’s speech synthesizer. The power of his mind was awe-inspiring. I remember thinking at the time, he’s exploring concepts that would never occur to 99% of us. Perhaps even more astonishingly, he was giving us answers to questions that it would never occur to most of us to even pose.

One of those questions was: Are we alone in the universe? Hawking’s answer was a resounding no. A series of slides cited irrefutable statistics: There are hundreds of billions of galaxies in the observable universe, each containing trillions of stars, a certain percentage of which likely have planets revolving around them, a small percentage of which likely contain the elements needed to support life (i.e., oxygen, carbon and other organic chemicals). The conclusion was inescapable: It was a virtual mathematical certainty that life must exist elsewhere, probably on many different worlds, not just one or two of them.

Then he dropped a bombshell. Why then, the next slide asked rhetorically, have we not heard from these other living beings yet?

Hawking’s theory: Because life as we know it is a human conceit. We assume that the evolutionary process here on Earth (i.e., simple one-celled creatures mutating over a long period of time into complex animals with increasing brain size) is universal … literally. But, he asked rhetorically, is it not just as possible that the process of evolution is completely different on other worlds? Is it not just as possible that what we consider “intelligent” life is completely different elsewhere? That what those life forms need to survive and evolve is completely different from what we need? That their means of communication is completely different from anything we are capable of perceiving?

My mind was blown that day — I could almost feel my head going poof! — and it continues to be blown whenever I think back to that magical afternoon when the greatest thinker of our time shared his ruminations in a darkened auditorium with a few thousand privileged souls. And make no mistake — I consider myself privileged to have been there.

The recent 50th anniversary celebrations of the first moonlanding (an event recalled so profoundly here by my esteemed colleague Anthony DeCurtis) stirred my memories of the Hawking lecture, and also got me thinking about the Voyager 1 probe launched by NASA in 1977.

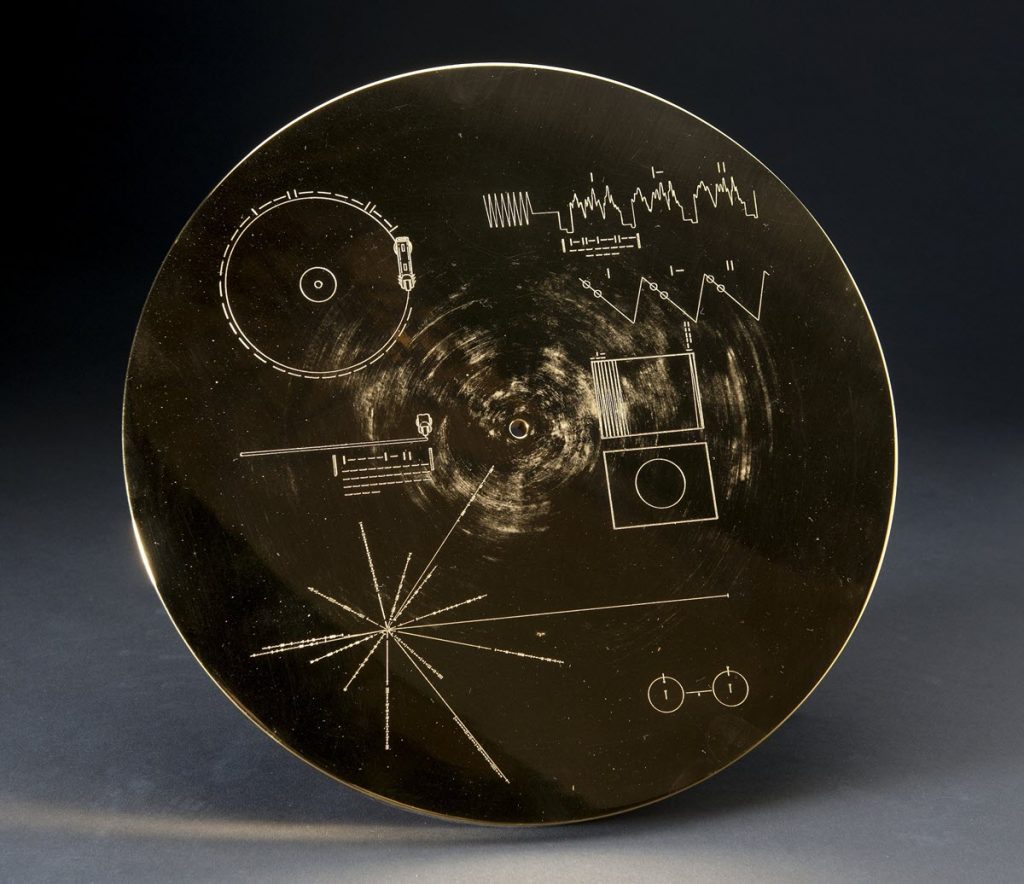

Voyager 1 is currently the farthest human-made object from Earth. It’s already reached interstellar space and will encounter its first star in about 40,000 years. Even though astronomers believe this particular star may not have planets revolving around it that can sustain life, this is nonetheless significant because the probe houses a time capsule intended to communicate to extraterrestrials a story of the world of humans on Earth. Inside the capsule are numerous written documents, drawings and photographs, plus two phonograph records (talk about the resurgence of vinyl!) that present a variety of natural sounds, such as those made by surf, wind, thunder and animals (including the songs of birds and whales), as well as spoken greetings in 55 ancient and modern languages … and music.

The aliens who are fortunate enough to encounter these records and figure out a way to play them (pictorial instructions are included) will be treated to a variety of selections, including Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto, Mozart’s The Magic Flute, Beethoven’s Symphony Number 5 and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, a momentous work whose tumultuous debut was described in one of my previous blog postings. Also included are performances by bluesman Blind Willie Johnson and jazz legend Louis Armstrong, as well as Chuck Berry’s raucous “Johnny B. Goode,” a mainstay of every bar band on the fine planet we humans inhabit.

Will “Johnny” eventually assume that same status on other planets light-years away, with twelve-legged aliens duckwalking across the rickety stages of extraterrestrial drinking establishments serving cocktails made from nitric acid and sulfur, garnished with a plutonium twist? Likely nobody reading this blog (much less the author) will be around to find out the answer to that question.

But I sure would like to think so. And I have a feeling Stephen Hawking will be dancing along.

Photograph of Stephen Hawking by Paul. E. Alers/NASA via Getty Images; photograph of the Voyager 1 record cover courtesy of NASA.