Tagged Under:

Build Diversity in Your Repertoire

Try these five ways to build more diversity in your repertoire.

Indiana University Bloomington music students circulated a petition calling for more diversity across the music school’s curriculum.

These students were motivated by the dialogue about systemic racism following the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and others. They also met with the conductors of Indiana’s large ensembles, asking for diverse concert programs too.

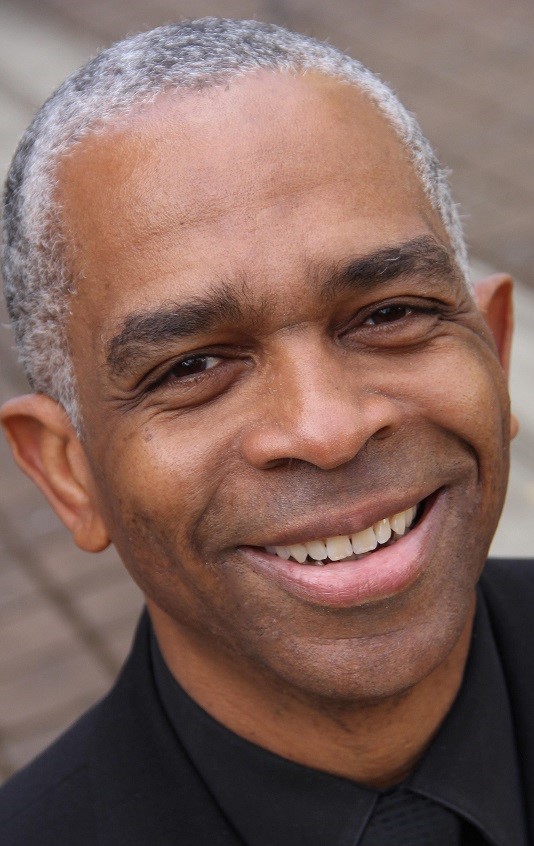

The discussion led Dr. Rodney Dorsey, the chair of the Department of Bands, to explore the possibility of joint projects with Indiana’s Latin Jazz Ensemble and ballet program. But he’s recognized the lack of diversity in music for years. As a student, he remembers telling his parents that he didn’t see many Black men leading college bands.

The discussion led Dr. Rodney Dorsey, the chair of the Department of Bands, to explore the possibility of joint projects with Indiana’s Latin Jazz Ensemble and ballet program. But he’s recognized the lack of diversity in music for years. As a student, he remembers telling his parents that he didn’t see many Black men leading college bands.

Throughout the last decade, music educators have been acknowledging the need to build concert programs that include a diverse range of composers and musical styles.

Falling back on the classics, typically written by white men, means that a broad swath of students will rarely perform music written by somebody who looks like them or is familiar with their culture, says Dr. Cory Meals, head of analytical activities for the Institute for Composer Diversity, a group based at the State University of New York at Fredonia.

“We need to be mindful of the constellation of other information swarming around any given work: the composers themselves, their backgrounds, their stories, and how those stories intersect or reflect those of our students and communities,” says Meals, who is also assistant professor in music education at the University of Houston.

When building a diverse repertoire for your music program, try these five tactics.

1. Learn Where to Look

According to research from the Institute for Composer Diversity, white men wrote nearly 95% of the pieces on suggested repertoire lists for school bands in 23 states. Therefore, state lists should not be the only source for programming ideas, says Liz Love, band director at Grisham Middle School in Austin, Texas.

According to research from the Institute for Composer Diversity, white men wrote nearly 95% of the pieces on suggested repertoire lists for school bands in 23 states. Therefore, state lists should not be the only source for programming ideas, says Liz Love, band director at Grisham Middle School in Austin, Texas.

Meals recommends sites such as the Institute for Composer Diversity, …And We Were Heard and the Kassia Database. Self-published composers, smaller publishers such as Meredith Music Publications and co-ops like the Blue Dot Collective can also turn up new options.

Following minority composers on social media may also provide inspiration. When Love and her students went to the University of Texas at Austin to sit in on a college rehearsal, they met Omar Thomas and later performed his soulful rendition of “Shenandoah” at the 2019 Midwest Clinic International Band and Orchestra Conference. Some of Love’s students started following Thomas on Instagram and shared their excitement about his updates.

2. Consider Commissioning

Commissioning new pieces can be costly, but bands can split the composer’s fee through consortiums or other creative means.

While conducting the University of Oregon wind ensemble in 2016, Dorsey received a faculty grant to commission a piece by Andrea Reinkemeyer called “The Thaw” for voice and winds. Reinkemeyer had attended Oregon as an undergraduate student.

Love sought support from the Grisham Band community to pay for a commissioned work, also performed for the 2019 Midwest Clinic, called “Everybody Sang (In a Universal Language)” by composer Jack Wilds. The piece features folk songs from China, Mexico and Bulgaria, capturing Grisham’s diverse population.

Love says that Wilds, a white composer, was worried about appropriation, but the composition was a collaborative effort. Love had reached out to her students and their families to get feedback about their favorite folk songs. The work resonated with families, including a father who “was surprised and elated that, as part of [his daughter’s] schooling, she was to play something that he recognized,” Love says.

3. Think Inclusively

When creating a concert program, don’t focus on a single type of composer, such as all female or all Black, Meals advises. That situation can lead to “othering,” suggesting that underrepresented individuals are different or separate in some way.

Instead, when planning concert programs, he recommends a one-to-one ratio. For every Gustav Holst, Paul Hindemith or other classic, feature a work by an underrepresented composer.

4. Go Beyond the Music

While Dorsey plans to program more pieces by under-represented composers going forward, he has made efforts to incorporate them into his concerts in the past.

For the Indiana University wind ensemble two years ago, he featured “AMEN!” by Carlos Simon and the “‘Heritage’ Concerto for Euphonium and Band 2014” by Anthony Barfield.

Dorsey takes time to educate his students about the people behind the music. “At the start of the rehearsal cycle, I will talk about the composer and any pertinent information about the piece,” Dorsey says.

Performing newer works also creates the opportunity for students to meet composers directly. Barfield attended the Indiana concert. Reinkemeyer attended the dress rehearsal and premiere at Oregon.

5. Be Brave

Finding new material and learning to teach it take effort. Some band directors may shy away from unfamiliar musical cultures, styles or composers for fear that “they [might not] have the background, training or knowledge to navigate the musical and cultural content successfully,” Meals says.

Finding new material and learning to teach it take effort. Some band directors may shy away from unfamiliar musical cultures, styles or composers for fear that “they [might not] have the background, training or knowledge to navigate the musical and cultural content successfully,” Meals says.

To remedy this, he recommends a three-phased approach. First, learn more about the piece. Dive into any resources the composer has offered. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings and the Routledge World Music Pedagogy Series can help.

Second, connect with culture bearers who can provide context to the musical piece. That person could come from your community, from a local university or from within your own school. “Look broadly and be inclusive,” Meals says.

Finally, once you’ve performed the piece, re-engage that culture bearer to ask what went well and how you and your students might improve your understanding. “We’re educators,” Meals says. “We should also be lifelong learners.”

Photo by Shawn Chaney

This article originally appeared in the 2020N3 issue of Yamaha SupportED. To see more back issues, find out about Yamaha resources for music educators, or sign up to be notified when the next issue is available, click here.

This article originally appeared in the 2020N3 issue of Yamaha SupportED. To see more back issues, find out about Yamaha resources for music educators, or sign up to be notified when the next issue is available, click here.