Tagged Under:

Case Study: Intentional Music Programming Allows Students to Enjoy the Journey of Music-Making

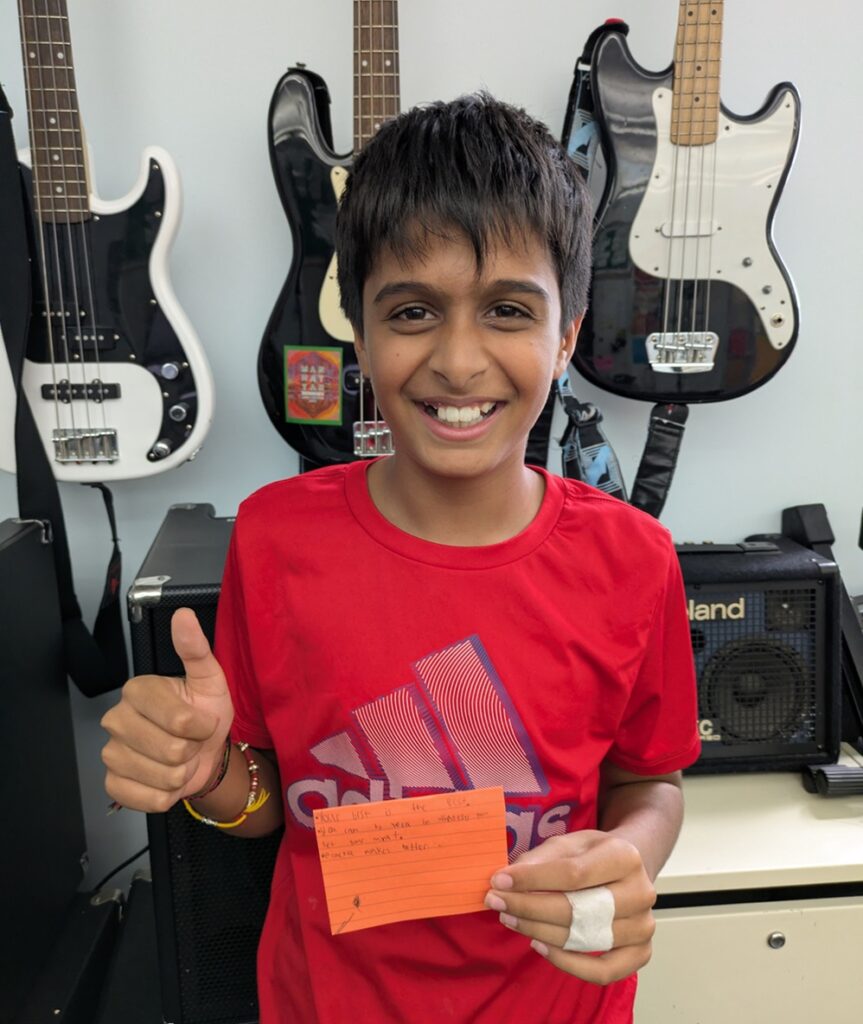

Finding “mini-opportunities” for students to perform is the main element of this Yamaha “40 Under 40” music educator’s teaching philosophy.

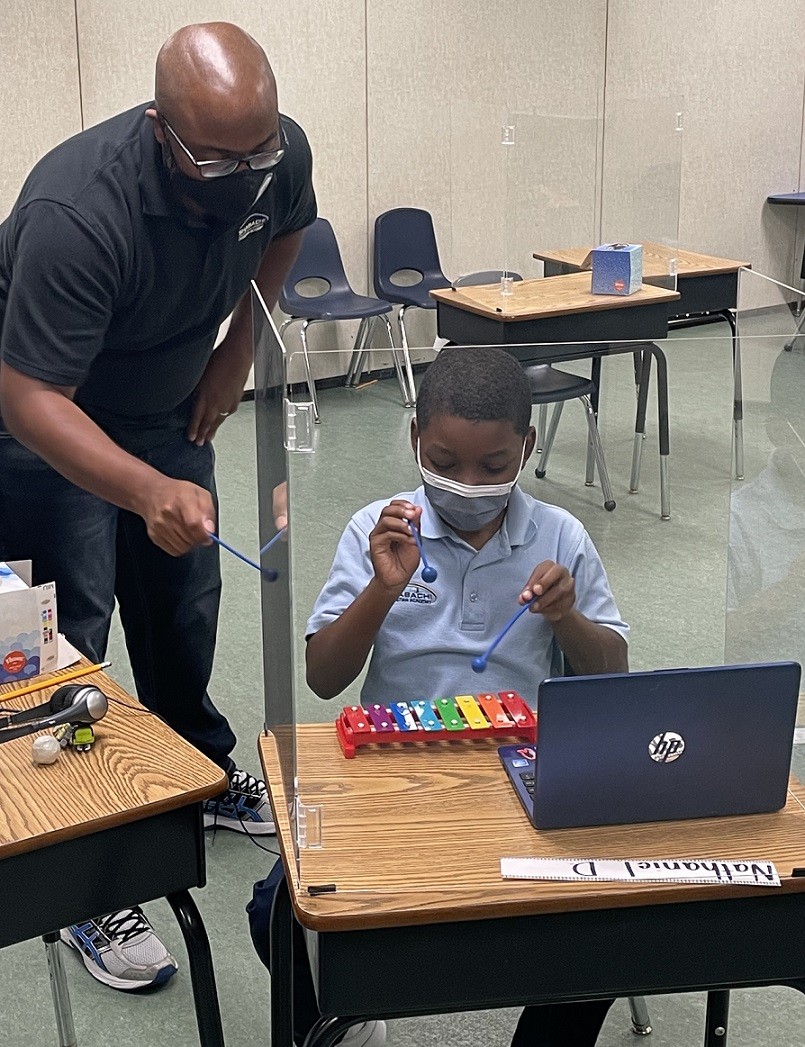

While most music educators plan for one or two big annual performances, Brandon Felder, the music director of SHABACH! Christian Academy in Landover, Maryland, tries something different.

“I’ve always been of the mindset that we should not work for just one culminating activity but rather a continuum of different experiences,” he says.

Felder achieves this continuum of experiences through what he calls “intentional music programming.”

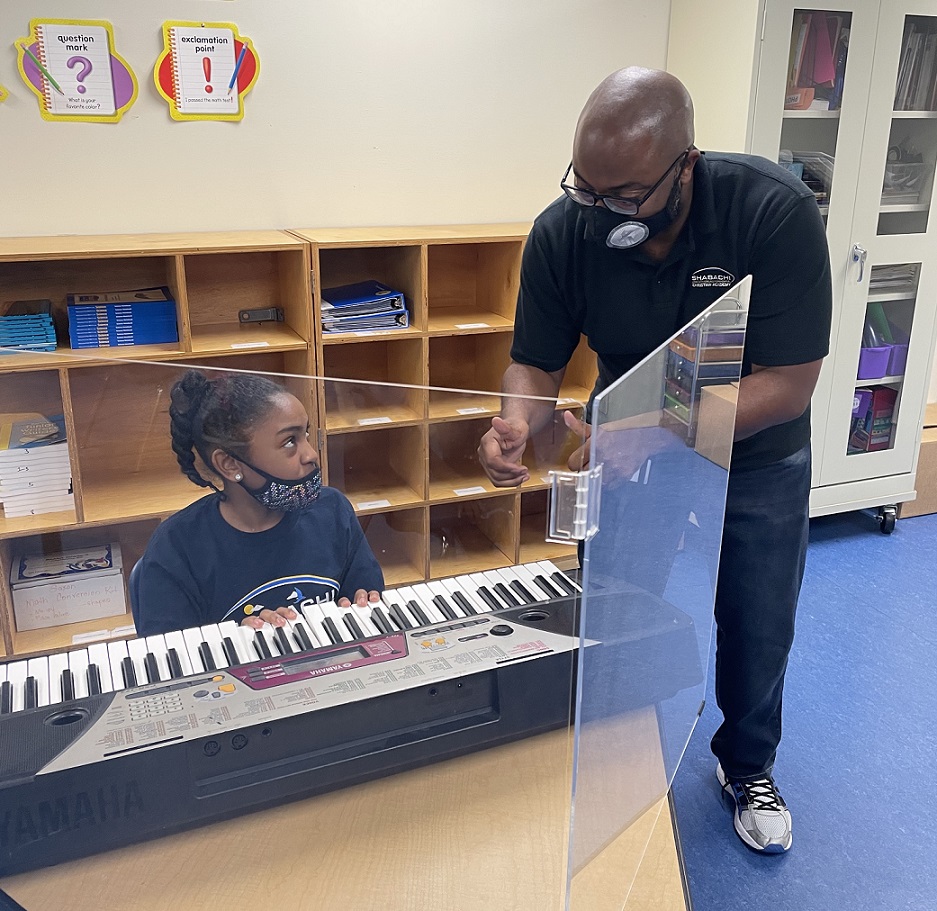

“I cannot emphasize enough the importance of students performing in public, so I regularly organize small classes for my students to play through their pieces to gain confidence in front of an audience,” Felder says. “I also try to arrange informal performances for them to gain further experience before their formal concerts.”

By performing often, not only do students develop their musicianship, but they also develop life skills like teamwork and the ability to manage projects, time and stress. “The wider experiential base allows for the brain to understand complex information and meaning,” Felder says. “Performance experience provides more anchors for the brain to process and function … and it helps students develop into responsible citizens with a sense of purpose, accomplishment and a deep appreciation for the arts. This is the most satisfying achievement for me as a teacher.”

Branching Out of the Classroom

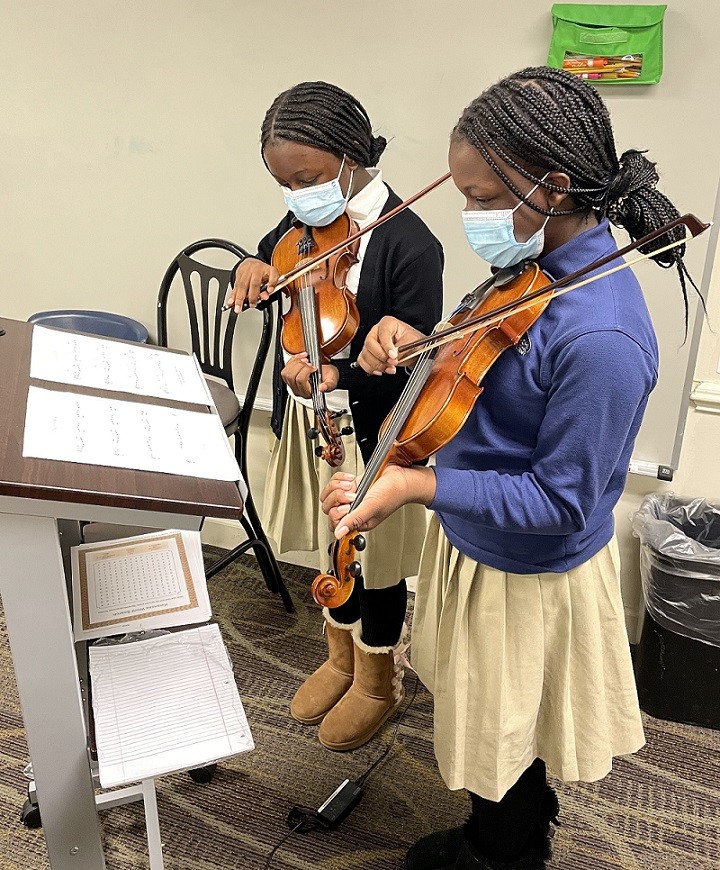

For Felder, music education should be more about the journey than the destination. That means creating what he calls “many mini-opportunities” for students to practice and perform outside of the classroom. He says it’s important for students to perform for different crowds and to “allow their music to be heard more than just once.”

For Felder, music education should be more about the journey than the destination. That means creating what he calls “many mini-opportunities” for students to practice and perform outside of the classroom. He says it’s important for students to perform for different crowds and to “allow their music to be heard more than just once.”

According to Felder, the journey his students go on should not stop in the classroom. So, he sets up experiences and opportunities for his students to interact with and perform for members of the community. He starts within a 3- to 5-mile radius from SHABACH. That way, students don’t have to travel far, and spectators are members of their local community.

To find new opportunities, Felder first goes to places that fit into what he calls the HEAR Perspectives: Humanitarian, Educational, Artistic and Religious institutions. One week, Felder might take his students to a bookstore and have them perform a recital or go to a local college and take a tour of the music department. Another week, they might play for patients at a nursing home, sing for people at a soup kitchen or perform for a church fashion show.

Finding Balance

Intentional music programming is not a new idea for Felder. “It’s a full circle thing for me,” he says.

During his high school years, he experienced a more traditional approach to music programming. However, Felder was also afforded wonderful on-the-fly opportunities, like a last-minute phone call to back up country superstar Shania Twain when he was a freshman in high school. “We’ve all felt those goosebump moments, so the more often that students have those opportunities, the more chances they have for their skills to transfer from the four walls of the traditional classroom mindset and beyond the traditional music class curriculum,” he says.

Felder says that he now tries to offer those big showstopping moments for his students, as well as more local, community-based opportunities. So, whether he is recruiting artists on Cameo to make virtual appearances at SHABACH recitals or working with a local piano store to host a recital where his students could play on top-of-the-line instruments, Felder says he tries to stay flexible and think outside the box.

The Five Cs of Intentional Music Programming

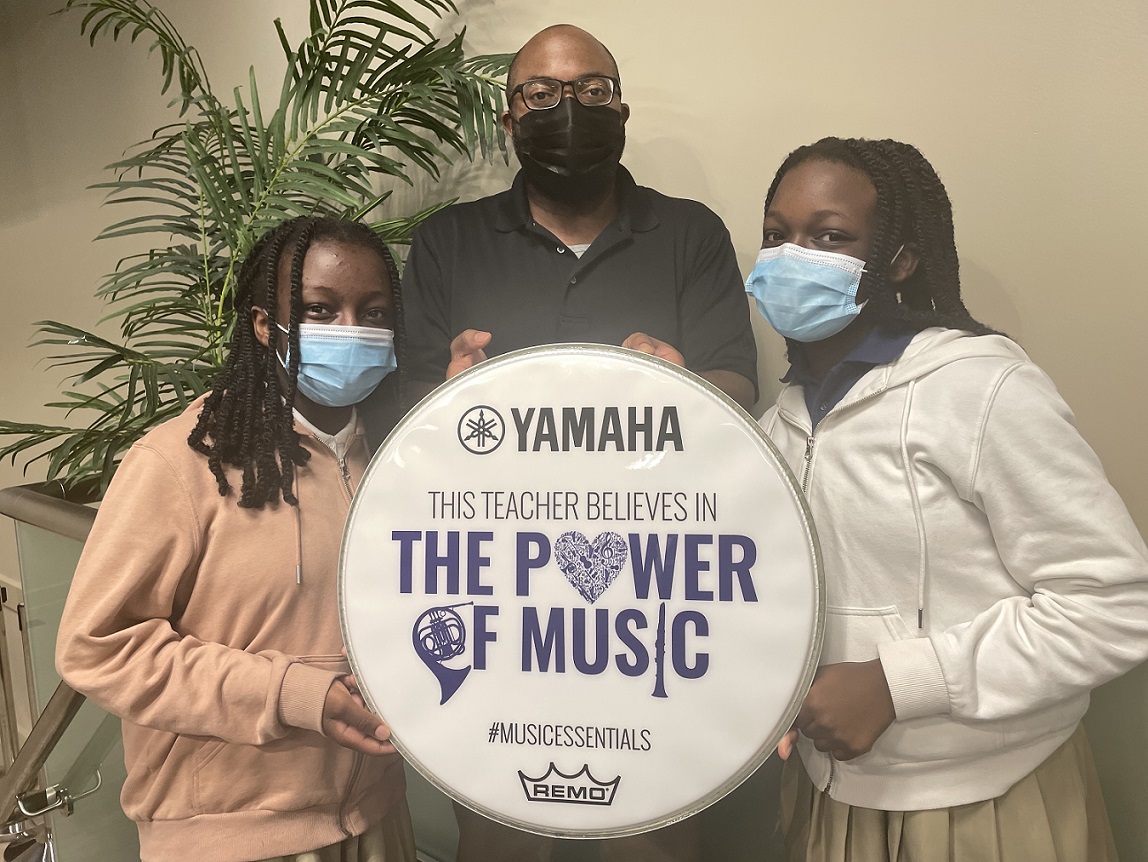

Mini-opportunities serve multiple purposes, Felder explains. First, they allow his students to give back to their communities. They also introduce his students’ art and music to members of the community who may not otherwise be exposed to it. Felder says that at their spring shows, he’ll often see people who first experienced the SHABACH music program during one of their mini-opportunities.

Mini-opportunities serve multiple purposes, Felder explains. First, they allow his students to give back to their communities. They also introduce his students’ art and music to members of the community who may not otherwise be exposed to it. Felder says that at their spring shows, he’ll often see people who first experienced the SHABACH music program during one of their mini-opportunities.

Felder wants these mini-opportunities to provide both students and spectators with “two shots and a booster: Two shots of curiosity and empathy and a booster of optimism in every musical presentation.” He says that whatever they decide to do musically, those three elements must to be accounted for because “music has the power to transform mind and spirit, in addition to allowing souls to communicate.”

Felder also looks for ways to emphasize what he calls his five Cs of intentional music programming: Creativity, Collaboration, Community, Connection and Citizenship. In any opportunity that he finds, Felder asks himself if those fundamentals are met. “I’m always looking for opportunities that allow students to experience the five Cs,” he says.

The elements of the five Cs became especially important during the COVID-19 pandemic, when Felder hosted his music classes virtually. He found creative ways to continue following his intentional music programming method, by having students record voice memos of them singing or playing instruments, having socially distanced performances when they could, and even creating and filming an hourlong adaptation of “The Wiz,” featuring a red-carpet premiere, a mix of gospel and modern-day music, and, of course, dancing scarecrows.

Staying Energized

Felder says finding these curated opportunities can be challenging, so it’s important for him to stay personally energized about music. He sees himself as a “teaching artist,” meaning that he values the level of his own musical experience, while also trying to share that knowledge and love of music with his students.

Felder says finding these curated opportunities can be challenging, so it’s important for him to stay personally energized about music. He sees himself as a “teaching artist,” meaning that he values the level of his own musical experience, while also trying to share that knowledge and love of music with his students.

He “continually looks to fuel [his] own creative experiences through personal performances, examination and objective opportunities” before he can then feed his students’ passions. Whether that’s at SHABACH, his work as the music director of the Georgetown University Gospel Choir, performing his own music, or serving the D.C. chapter of the GRAMMYS® as Governor and Music Education Chair, Felder learns from and becomes energized by these experiences. He says it’s his responsibility as a music educator to take those experiences and the innovation and fresh ideas that come along with them and transform them into a meaningful curriculum for his students.

Felder says that if he’s excited about something, his students have an easier time buying into it, so staying energized is vital for him.

Staying Honest

It’s also important to be transparent with your students. “Life is still happening to us,” Felder says.

It’s also important to be transparent with your students. “Life is still happening to us,” Felder says.

Because he shares how he’s feeling with his students, they can learn empathy and compassion. When they see that Felder has had a tough day, but he’s still there, ready to teach, he says they learn resilience and how to push forward. And finally, when they see him turn to music to deal with his emotions, they learn that they can do the same thing in their own lives.

The more honest he is with his students, the more that honesty is reciprocated. “I want my classroom to be a safe space where students can share and where there is comfort,” he says.

Sometimes, that means making on-the-fly adjustments to the curriculum when big events happen. “I sometimes allow the energy and the feelings of the students dictate where the programming may go,” he says.

By pivoting, he can reinforce collaboration, as well as show students that they can use music to express their emotions.

Felder is also transparent with the curriculum he teaches. He analyzes the history behind famous songs with his students. They debate whether certain lyrics are still applicable today and hold discussions on which parts of songs to stress during live performances. This collaborative way of music programming helps students feel that their voices are being heard and that they have input in their performances.

Finding Success

Felder insists that there is no cookie-cutter way to attempt intentional music programming and that each group of students should have curated programs for their own needs and situations. To be successful with this type of curriculum, Felder says you must find balance and learn what works best for each group of students. And, perhaps most importantly, it’s about staying flexible and being able to change direction when a situation arises that can’t be ignored.

Felder insists that there is no cookie-cutter way to attempt intentional music programming and that each group of students should have curated programs for their own needs and situations. To be successful with this type of curriculum, Felder says you must find balance and learn what works best for each group of students. And, perhaps most importantly, it’s about staying flexible and being able to change direction when a situation arises that can’t be ignored.

It’s also important to reexamine how most music educators measure success. Felder says intentional music programming has deepened his music program in a qualitative way. While he acknowledges that numbers matter, he prefers to measure growth differently.

If a program grows too fast and has too many participants, Felder is not able to fully reach all of his students, which he sees as problematic. “Sometimes, we look at how we scored on a certain assessment instead of noting that ‘this student’s range of knowledge has grown’ or ‘this student’s vocal range has grown’ or ‘their experiential range has grown,’” he says.

This type of data is more important for Felder’s own goal of helping his students flourish. “My goal is not to make the next Beethoven or Justin Bieber or Beyoncé, but just to make well-rounded citizens,” he says.

Felder hopes that the lessons his students learn in his music programs set them up for success, regardless of what they do. He especially loves when former students come back to remind him of moments or performances that he’s forgotten. Felder says that’s ideal for him — that some performance or show he’s curated, big or small, has stuck with his students for years. This proves the core message of his intentional music programming: Give students as many opportunities to perform as possible and allow them to appreciate their journeys just as much as their final destinations.