Tagged Under:

Teaching for Artistic Behavior

TAB pedagogy may look like chaos, but it’s a unique teaching methodology that allows student-led creative exploration.

Opening the door to Emily Meyerson’s music classrooms in the North Baltimore Local Schools in Ohio reveals what looks to the naked eye like a scene of chaos: Students may be playing electric guitars, creating electronic music on iPads, building their own drum kits out of coffee cans, or singing while their friends accompany them on ukuleles. A closer look reveals one student working on a year-long graphic novel project about music, while another conducts research on the euphonium, and another collaborates with a group of friends to form a miniature band of their own.

This type of student-led creative exploration comes from a pedagogy called “Teaching for Artistic Behavior” (TAB). Meyerson, who teaches general music for kindergarten through 6th grade, began implementing TAB concepts into her classroom nearly a decade ago, and the process has only evolved and improved.

According to the TAB pedagogy website, the guiding principles include statements like “The child is the artist” and “The classroom is the child’s studio.”

The original intention of TAB pedagogy was for use in visual arts classrooms; however, Meyerson and other music teachers are now finding ways to implement the same principles in elementary music education. “So much of school has become [about] straight lines, no talking … kids have to have an outlet to be kids,” Meyerson says.

The Artistry of Music

Because TAB originated in the world of visual arts, Meyerson first learned of the pedagogy through a friend who teaches art classes. “My best friend was hired as our visual art teacher at the elementary school. Because we were already friends, and we have similar outlooks on education, we wanted students to be able to collaborate between our classrooms. We’re both into exploring through play,” she says.

A core concept of TAB pedagogy is the “open studio,” or a space where students can freely explore with various artistic media, setting their own goals along the way. “It’s made for visual art, so the ‘open studios’ [might include] a painting studio, a drawing studio, a sculpture studio,” Meyerson says. “I wasn’t sure what that would look like for me, so I tested out a lot of things.”

After getting involved in TAB Facebook groups and gaining advice from other teachers, Meyerson started equating different instruments with different artistic media. The open studio became a place for musical media experimentation. “Instead of painting, it’s drumsets. Instead of drawing, it’s keyboards,” Meyerson says.

An obvious difference between the visual and musical arts is the noise involved. While many students can work on visual projects individually, balancing the conflicting noises of students simultaneously playing different instruments is more of a challenge. “Every class brings headphones with them. Most of the instruments I have are electric: electric drumsets, keyboards, electric guitars [that students] can plug headphones into,” Meyerson says.

Meyerson also keeps a container of headphone splitters in her classroom so two students can collaborate on a project, listening to the same source, while using headphones.

Students also have modifications available to keep the classroom as calm as possible. “I have a 6th grader who’s working on a project about the euphonium,” Meyerson says. “We’ve talked about, ‘You can buzz on your mouthpiece, or you can work on your fingerings without playing.’”

Meyerson’s classroom also includes a sound-dampening studio area that the school’s custodial staff helped her build. When Meyerson’s students, like the student working on the euphonium piece, are ready to record something for their final project, they can go into the sound-dampening studio area and play their instrument at full volume.

Though Meyerson, who was recognized as a 2023 Yamaha “40 Under 40” educator, takes some precautions against the noise, she also acknowledges that her classroom is allowed to get a little crazy. “The reality is, it’s loud,” she says. “But the kids have found a way to work through that. They’re so focused on what they’re working on.”

Sometimes, the noise can even benefit students. When a student becomes distracted by someone else’s project, it often leads to a conversation about the different elements of music both students are exploring.

A Typical Day for TAB

While the open studio is a key component of TAB, Meyerson uses this concept alongside more traditional teaching methods to make sure that her students are meeting music education standards.

A typical day for a 3rd-, 4th-, 5th- or 6th-grade student in Meyerson’s classroom begins with a seven-minute lesson. Meyerson sets a timer at the start of class, then uses this time to have the class work together. “I do a demo, or I might teach skills, or we might do little task parties where they demonstrate a certain skill,” Meyerson says. “For example, I tell students, ‘You have to show me you can do XYZ on the keyboards before you can use them.”

Once the seven minutes are up, the rest of class time is devoted to the open studio. However, amidst the free experimentation is a quarter-long project that students can work on at their own pace. At the start of each quarter, students have a check-in with Meyerson where they present their project idea. Then, throughout the rest of the quarter, they can budget their open studio time to make progress on their project, ask Meyerson or other students for help, or experiment with different musical modalities.

Once students have committed to their projects, Meyerson serves as a guide and facilitator, helping those students bring their ideas to life. “The fundamentals of TAB means the music studio is their studio. They’re musicians. I’m the facilitator,” she says. “Either kids are working and I’m checking in on [and] helping them, or sometimes [I’m sitting at my desk] with a line of kids who are like, ‘I have a question!’”

Project Parameters

Students have three main parameters they must follow for their projects: a) it must be related to music, b) it must be something the student is excited about learning, and c) it must be a project that shows at least three to four class periods’ worth of work.

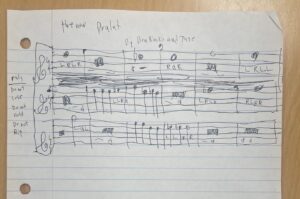

With those guidelines in mind, students have presented a variety of creative ideas that reflect their diverse interests. “I have a kid who’s composing a keyboard song, and his friend built a drumset out of coffee cans and tinfoil. They’re composing a song together,” Meyerson says. “I have kids who do singing projects [and] collaborate with a friend playing the ukulele. Last year, I had a group who made a band with two kids playing electric guitar, one kid playing drumset, and a singer. It was super cool to watch them as the year went on.”

Often, students will create interdisciplinary projects that include other interests of theirs, like visual art. “I’ve had kids create children’s books before,” Meyerson says. “They can take those projects back and forth between the art studio and music studio.”

Some students may even choose to take on a year-long project with quarterly progress check-ins. One of Meyerson’s current students is writing a graphic novel including a villain that removes all the music from the world. “That’s not a project that he can finish in six weeks,” Meyerson says. Instead, this student checks in with Meyerson every quarter to show his progress, with the goal to complete the graphic novel by the end of the school year.

When students take on bigger projects, Meyerson emphasizes her classroom’s tenet “engage and persist.” While students may make changes to their project during the course of a quarter or school year, students must find a way to see their projects through to completion.

Building Skills, Building Scaffolds

The “open studio” model core to TAB requires that students have some basic knowledge of music with which to explore; as a result, implementing TAB looks different in a kindergarten class than it does in a 6th-grade class.

For her K-2 classes, Meyerson begins the school year with more structured instruction while slowly introducing TAB concepts. “In kindergarten, we don’t start any TAB stuff until the end of the year,” Meyerson says. “In a 30-minute class, we might have 20 minutes of structured activity and 10 minutes at the end where [students can choose].”

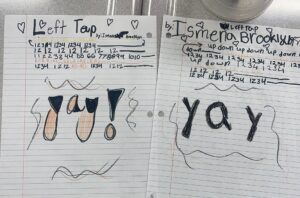

In her 1st- and 2nd-grade classes, Meyerson gives her students what she calls “choice time,” or time where they get to explore in the open studio. Instead of choosing their own projects, students have quarterly song challenges, in which they create their own songs to present.

By the time students reach 3rd grade, most have been slowly introduced to TAB, so they’re ready to start brainstorming project ideas of their own, managing their time to complete their projects, and experimenting with more instruments and technology.

The Beauty of Organized Chaos

In using TAB pedagogy, one of the biggest obstacles Meyerson has faced is parents who don’t understand the concept. “What the kids are producing is kid-level music and kid-level art,” Meyerson says. “Parents are looking at that and saying, ‘I’m used to my child learning the same song for the Christmas program.’”

One way Meyerson has helped parents understand the benefits of TAB is through a yearly “make-it, take-it” night that the school hosts in the spring. On this night, parents, families and community members are invited to see their students’ work. “We take what we do in our classrooms and set it up across the entire school,” Meyerson says. “The kids can be facilitators and walk their parents through what they do in art [or] music class. That helps a lot.”

Thankfully, Meyerson has had the complete support of the school’s administration. “Our principal loves what we’re doing,” she says. “She’s been on board since the beginning.”

Meyerson has also begun spreading the word about TAB to other music educators throughout the country. “I’ve presented at the Ohio Music Educators Association and at the National Association for Music Educators,” Meyerson says. “Other music teachers are starting to reach out to me.”

Meyerson has noticed that other teachers are afraid to implement TAB pedagogy into their classrooms because of its non-traditional nature. “There was a day when the kids were all in here working, and I was sitting at my desk watching them work,” she says. “I was feeling so guilty! But they were really engaged and excited about what they were doing.”

At the end of each quarter, Meyerson examines each student’s final project and asks the students to reflect on their process, often using questions like, “What is a specific thing that makes it really special?” and “What is something that was challenging, and how did you solve it?”

TAB is not just about getting students to learn the material; it’s about getting them to think like a creative artist. “The end goal is that they’re leaving here learning how to be a musician,” Meyerson says.