Tagged Under:

Teach Holistic Music Literacy, Not “Button-Pushing”

Focus on teaching music as a language and give students the skills to develop fluency in improvising, reading notation, composing and audiation.

Do you recognize the scenarios listed below? Struggles like these are all too familiar in music classrooms:

Letter names scribbled under every note.

Letter names scribbled under every note.- Referring to notes as fingerings, not pitches.

- Requiring multiple run-throughs to finally be able to “read” the music.

- Failure to notice incorrectly performed pitches.

- Ultimately, students quitting due to frustration.

For many years, my students struggled with these exact issues. Then, that lightbulb moment: I realized that I was the root cause. I was teaching button-pushing, not holistic music literacy.

So, what do I mean by button-pushing? Bassist Victor Wooten summarizes it best: “Although many musicians agree that music is a language, it is rarely treated as such.”

As a band, orchestra and general music teacher at Park Spanish Immersion Elementary School in St. Louis Park, Minnesota, I realized a few years ago that I was not teaching music as a language — that is, music literacy. Rather, my curriculum centered on the technical execution of music notation on instruments (aka button-pushing). This approach was leading students into the pitfalls listed above. My teaching was sending the message that music symbols represent fingerings rather than sounds. Upon reflection, this was akin to teaching someone to type in a language they didn’t understand.

What, then, is holistic music literacy? Within languages, literacy is typically defined as fluency in speaking, reading, writing and understanding. Similarly, music literacy can be defined as fluency in improvising, reading notation, composing and audiation (aural comprehension). That’s right, fluency in all four areas comprises holistic music literacy.

Unfortunately, my former button-pushing curriculum was not setting up students to achieve holistic music literacy. Every year, I saw the same struggles, and I knew that something needed to change. So, I dove in. I read about the mother-tongue approach of Shinichi Suzuki and the audiation research of Edwin Gordon. I gained much insight from the writings of Stanley Schleuter. And I engaged the English and Spanish teachers and the speech-language pathologist at my school to learn from their expertise. I even joined a cohort of reading and spelling teachers in a two-year course called LETRS in order to develop a deep understanding of the science of reading. In summary, literacy is not achieved through a visual memory process, it’s achieved when symbols and sounds connect to create meaning. The alarm bells went off: This could just as well describe music!

As a result of this learning, my music program looks very different today. I made two significant shifts. First, similar to immersion language-learning, my students learn sound before sight. Second, when I introduce music notation, I base my instructional approach on the science of reading.

Sound Before Sight

“Acquiring verbal skills is dependent mainly on the ability to hear and discriminate sounds and then attach meaning to them. Acquiring musical skill and understanding is also dependent mainly on the ability to hear and discriminate sounds and attach meaning to them.” — Stanley Schleuter

The basic principle of sound before sight is that aural comprehension precedes theory or grammar, similar to how humans learn language. Keep in mind that aural comprehension is not the same as rote memorization. The two can be distinguished by the following analogy: Imagine you had to memorize a speech in a language that you don’t comprehend. You might be able to say the sounds mostly correctly, but you don’t understand what you’re saying, nor could you use the words you’ve memorized to improvise new sentences. In music, a student might memorize a piece but make a pitch error and not notice. They may be unable to identify a tonal center or whether the piece is in major or minor. And perhaps they are unable to take an excerpt and transpose or improvise on it.

The basic principle of sound before sight is that aural comprehension precedes theory or grammar, similar to how humans learn language. Keep in mind that aural comprehension is not the same as rote memorization. The two can be distinguished by the following analogy: Imagine you had to memorize a speech in a language that you don’t comprehend. You might be able to say the sounds mostly correctly, but you don’t understand what you’re saying, nor could you use the words you’ve memorized to improvise new sentences. In music, a student might memorize a piece but make a pitch error and not notice. They may be unable to identify a tonal center or whether the piece is in major or minor. And perhaps they are unable to take an excerpt and transpose or improvise on it.

In language, we stop imitating when we understand meaning and can converse. Similarly, in music we stop imitating when we can “think in sound” and improvise with meaning. That’s the difference between rote memorization and comprehension.

To teach sound before sight in my classroom, I use the following strategies:

- Delay the introduction of notation: I typically wait a few months before introducing method books or sheet music. This provides the time, space and focus to develop a solid aural foundation.

- Encourage experimentation: For example, spending time playing with tonal patterns. This might look like students learning a three-pitch pattern by ear, and then deleting, substituting or switching pitches to create a new pattern, or combining patterns together to create a longer melody. This kind of early experimentation, unconstrained by the complexity of notation, quickly exposes beginner students to a broader vocabulary of pitches — no matter the key signature — and also makes introducing transposition easy because students focus on patterns and relationships between pitches.

- Center improvisation: Beginners in my classroom create their own pieces as soon as they learn the first few notes on their instruments. We engage in “musical conversations” during class, wherein students sit in a circle, say a “sentence” to a peer and their conversation partner “answers” — all without using any verbal language, only music. This exercise emphasizes musical meaning, as students are quite literally conversing through musical sounds. In addition, I center student improvisation in performances, so the pressure to frantically learn concert music is removed, and we can dedicate the space and time required to build music literacy, not just “teach to the test.” Here is a fun video example of an improvised soundtrack to a short film, which my students performed in a concert setting.

The Science of Reading

“Children who learn to read well are sensitive to linguistic structure, recognize redundant patterns, and connect letter patterns with sounds, syllables, and meaningful word parts quickly, accurately, and unconsciously. Effective teaching of reading entails these concepts.”— Louisa Moats

Get ready for a hot take: A lot of sight-reading happening out there isn’t really reading at all. Stay with me. Often, sight-reading looks like giving students a new piece or exercise in their method book. They look at the sheet music but cannot hear what it would sound like in their head. So, they start to decode the first note symbol into the correct fingering, then the next and the next. Then they string it together, maybe with some unnoticed pitch errors. Were they reading?

Get ready for a hot take: A lot of sight-reading happening out there isn’t really reading at all. Stay with me. Often, sight-reading looks like giving students a new piece or exercise in their method book. They look at the sheet music but cannot hear what it would sound like in their head. So, they start to decode the first note symbol into the correct fingering, then the next and the next. Then they string it together, maybe with some unnoticed pitch errors. Were they reading?

I’d argue no. That kind of sight-reading is really just technical reproduction (or, one might even call it button pushing). Comprehension is an essential component of reading whether the text is familiar or unfamiliar, read in one’s head or aloud. In language, skilled reading requires word recognition and comprehension. Translating that into a music context: We need both pattern recognition and audiation to be truly reading notation.

Authentic sight-reading, aka just reading, means recognizing and deriving meaning from tonal and rhythmic patterns on sight. This doesn’t come from memorization but instead from fluency in matching symbol/sound relationships — a brain function called orthographic mapping. Training my students to memorize E-G-B-D-F or to identify note names on a page would be like trying to teach a student to read a book by asking them to name individual letters on the page, instead of decoding and blending the letter-sound correspondences. If you want to learn more about this idea in the context of the science of reading, listen to the podcast “Sold A Story” by education journalist Emily Hanford. There are significant parallels to music learning.

After my students build a solid aural foundation through sound before sight, I begin to introduce visual elements of music literacy. Here are a few tenants of my approach to notational instruction:

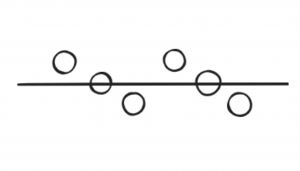

It has to be clear that notation is representation of a pitch, not of a letter name or a fingering: I postpone referring to notes by letter names for a few months in order to emphasize patterns and tonality. We use solfege or neutral syllables on each pitch. I start beginners on a one- or two-line staff to simplify patterns, emphasize the sound and symbol relationship, and deemphasize the inclination to name notes. Eventually I scaffold up to traditional notation.

It has to be clear that notation is representation of a pitch, not of a letter name or a fingering: I postpone referring to notes by letter names for a few months in order to emphasize patterns and tonality. We use solfege or neutral syllables on each pitch. I start beginners on a one- or two-line staff to simplify patterns, emphasize the sound and symbol relationship, and deemphasize the inclination to name notes. Eventually I scaffold up to traditional notation.- I constantly assess whether audiation is happening: For example, when reading from sheet music, we sing the excerpt or entire piece first before performing on instruments. There’s also a fun classroom game we play where I write a tonal or rhythmic pattern on the board. Students are challenged to echo every pattern I play except the pattern written on the board (which is the “poison” pattern!)

- I frequently use aural dictation and composition: In my room, we call them “music spelling tests”: transcribing short, performed patterns into notation. Students find it more fun than you might think! Students also write and perform their own compositions starting in year one.

Why True Music Literacy Matters

So, why does this shift to holistic music literacy matter? What are the stakes? I can’t say how many adults I’ve met who, at some point, got the message that they “just weren’t musical” or “just weren’t talented,” so they quit learning music. Unfortunately, this is still happening today. Stories like these, I believe, are the result of a way of teaching that often fails to impart holistic music literacy. The truth is: Musicality is an inherent human trait, just like language. With the right teaching, the musician in everyone can flourish.

So, why does this shift to holistic music literacy matter? What are the stakes? I can’t say how many adults I’ve met who, at some point, got the message that they “just weren’t musical” or “just weren’t talented,” so they quit learning music. Unfortunately, this is still happening today. Stories like these, I believe, are the result of a way of teaching that often fails to impart holistic music literacy. The truth is: Musicality is an inherent human trait, just like language. With the right teaching, the musician in everyone can flourish.

Does the switch to holistic music literacy work? Here’s what I’ve seen in my classroom:

- Students no longer write letter names on their sheet music.

- Students notice and self-adjust when they perform an incorrect pitch.

- Students are intrinsically motivated to play and practice, especially to share their own improvisations and compositions with others.

- Students are able to perform music at “higher grade levels” by ear, which increases their intrinsic motivation, excitement and self-efficacy.

- Students can transpose, often considered an advanced skill.

- Students are more likely to correctly read notation on their first try; in fact, they move through subsequent material faster than traditionally taught students.

- Students have not quit my ensembles out of frustration in years.

- The curriculum is more diverse, equitable, and inclusive, because it centers student voice and choice, not just the teacher’s.

Departing from a technique-centered approach was scary to me. I was diverging from years of practice and training — both in my own musical education and my education as a teacher. It felt vulnerable and was certainly perceived by some as totally counterculture to today’s music education norms. However, seeing students struggle was the strongest motivator for me. It made clear that research-based, systemic change is needed to best serve students, and frankly, to keep music education relevant.

As Dr. Christopher Azzara, a professor of music teaching at Eastman School of Music, says, we as teachers need to rethink teaching music so that it is more in line with how humans learn music. It is incumbent on music teachers to seek ever greater efficacy because students are so much more than just button-pushers.