6 Tips for Ear Training

Focus on ear training and intonation will improve.

“Tonight, we are young. So let’s set the world on fire …” There’s a minor sixth in Fun.‘s hit song “We Are Young.”

Music educators are always looking for new ways to connect with students, and with an increased focus on theory and intonation, ear training can be a surprising engagement tool to help ensembles improve their sound.

“It’s all about the ears,” says Rob Myers, coordinator of fine arts for the Arlington Independent School District and a former high school band director at Flower Mound High School, both in Texas. “Anything that you can do in an ensemble to sensitize the student’s awareness of what they’re doing or their responsibility in that ensemble comes back to the ears.”

Better listening skills can also create a more relaxed performance. Students won’t be as stressed once fitting into the ensemble sound starts to become subconscious.

“When you are focused on listening so intensely every day, the sound of the ensemble and your own individual sound relaxes because you can’t overblow or play with tension and still hear the pitch that you’re supposed to match,” says Michael Martin, trumpet player in the Boston Symphony Orchestra and a clinician who works with some of the nation’s top high school music programs such as Kennesaw Mountain (Georgia) and Avon (Indiana). “Ear training forces you to hear other things around you.”

Tip 1: Try Drones

Music educators have many ways to teach ear training. Some bands use keyboard drones to emit a concert F for the students to match. A drone can keep playing as long as necessary and isn’t subject to human inconsistencies, like tuning to a tuba or low reed player.

“The directors who … are the most consistently successful … work daily with drones,” says Martin, who is also the brass caption head and arranger for the Cavaliers Drum and Bugle Corps in Rosemont, Illinois. “They have big speaker systems set up in their band rooms and classrooms.”

Tip 2: Sing or Hum It

The first step in teaching pitch is getting students to internalize it. “Kids are constantly reinforced to match what they hear through singing, and for brass players through buzzing, and everyone through playing their instruments,” says Martin.

Singing is a helpful method, but sometimes students are hesitant or embarrassed to sing in front of their peers. “If they’re uncomfortable with singing … start by humming,” Myers says. “Have them place a hand over their chest, which will create a vibration when they hum. Get them to vibrate more by adding air to the vocal cords and opening their mouths. They’ll be singing and making a beautiful sound at that point.”

Tip 3: Connect Using Popular Music

When teaching about intervals, Martin suggests connecting with students’ current musical interests. “I’ve had a lot of success relating popular music to whatever interval or melodic material that I’m [teaching],” Martin says. “Pop music, rap music, movie scores, anything that I know 100 percent of the students are going to know and remember and be able to sing back to me because of how many times they’ve heard it.” For example, Martin uses the iconic first notes of the “Star Wars” theme to illustrate an open fifth or “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” for an octave leap. Challenge students to find more intervals in their favorite songs and bring them in for extra credit or another small incentive. Not only can educators share these with the class, but their library of examples to use will steadily grow.

Tip 4: Isolate Sections

With chords, Myers stresses the importance of isolating the sections in a wind ensemble setting.

“If the group is really struggling, then … isolate the woodwind choir and the brass choir,” he says. “You can have the brass hum or sing and have the woodwinds play, and then vice versa. It’s important for each of those choirs to get an opportunity to hear themselves in the ensemble setting to establish that choir sound.”

Tip 5: Mix it Up

Teachers may have a hard time shifting a school’s culture to incorporate more ear training. How do you keep students focused on these techniques if they’re uninterested or laser-focused on competitions? It takes patience and imaginative variety.

“Students are smart; they want to be good, and they’re going to recognize that they play better as an ensemble now because they’re better in tune,” Myers says. “I think the challenge is to bury the daily drill enough, or have new varieties to the daily drill that will pique the curiosity of an intelligent student.”

Myers recommends keeping ear training to about one-third of the rehearsal time (example, 15 minutes out of 45 minutes).

Tip 6: Focus for a Short Time

If at first you don’t succeed, Martin suggests trying to work on ear training for an even shorter amount of time.

“For students who are really not into it, I just barter with them … and say, ‘Give me five minutes of dedicated work on this concept of ear training, and then we’ll move onto something more exciting and can apply it in a more practical way,'” he says. “If the students are able to really focus for five to 10 minutes every day on something like this and see its importance, it won’t take long for them to see the results. They’ll start to play better and notice it, and they’ll be more enthusiastic about that engagement in the future.”

Use the Yamaha Harmony Director

A great tool to help students with ear training is the Yamaha Harmony Director (HD-200). This user-friendly instructional keyboard allows teachers to demonstrate beginning and advanced ear training techniques in an ensemble setting.

“The Harmony Director is the one-stop shop for everything,” says Martin. “You can use just intonation or perfect intonation based on exactly what you’re teaching. It’s like the coolest, nerdiest tool — and to me, cool and nerdy are the same.”

Develop a Lifelong Skill

Ear training is a lifelong skill, and every student’s learning curve is different.

“Don’t be afraid of it,” Martin says. “The pace of any classroom setting or rehearsal is the most important thing you need to focus on. Don’t worry about making it perfect every single day. Just do enough that you can continue to work on it the following day.”

As a program’s focus shifts to incorporate ear training, there will be some trial and error for the students and director alike.

“Directors [need] to recognize that they’re going to make mistakes, and it’s OK to acknowledge those mistakes to the students,” Myers says. “Just have the courage to try something.”

In the end, ear training, music theory and aural skills taught in high school provide an extreme advantage for students planning to study music in college and beyond. For Martin, learning ear training during his junior and senior years gave him an edge over others that helped propel him forward in his collegiate studies.

“Being proficient at ear training and being able to sing back something that you hear … I would say the higher your proficiency at that, the more enjoyable your musical career will be,” he says.

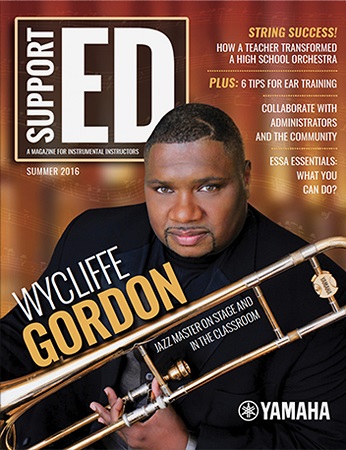

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2016 issue of Yamaha SupportED. To see more back issues, find out about Yamaha resources for music educators, or sign up to be notified when the next issue is available, click here.