Tagged Under:

Help Kids Who Want to Quit Before They Become Good

Students who show up and try but still struggle need help getting over “the hump.” Fluency-driven rehearsals may be the answer!

“I like band, but I always feel behind.” That’s what a student said before handing in her instrument.

She wasn’t upset or angry. She liked the class and the music, but every day, she felt like the only kid in the room who was faking her way through it.

After two years, she still couldn’t play in tune. Still couldn’t read rhythms without guessing. Still couldn’t find her place in the piece without someone whisper-counting it for her.

It wasn’t about effort. She showed up, tried hard and never caused a problem. But music never got easier, and this was exhausting.

She didn’t quit because she didn’t care. She quit because she never felt good at it.

Most Kids Don’t Hate Music. They Hate Feeling Lost.

We love to blame quitting on phones, sports or the mythical lack of grit, but most students leave band because they never got over the hump — that invisible tipping point where the instrument starts to make sense.

They’re not lazy. They’re stuck. And we can’t fix that by telling them to go home and practice.

The real work -— the structured climb toward fluency — must happen during rehearsal. If they never feel successful in front of you, they’re not going to chase it on their own.

I used to think, “If they just practiced more, this would click.” Then, I started looking at the kids who did practice — they were still struggling, just with slightly cleaner mistakes. It wasn’t a time thing. It was a clarity thing.

That’s the lesson for teachers: Some practice is necessary, but not endless hours. Just enough to get kids over that first hump, where the horn stops fighting them and they start to feel competent.

Scales and long tones still aren’t fun, but they stop being meaningless. They become a way to keep that feeling of competence going.

What Does Getting Over the Hump Look Like?

For the student, it’s when:

- They can play the scales in the key of the pieces you program (even slowly) without constant stops. For most band groups, this range is from three flats to one sharp.

- Their fingers and tongue stop fighting each other.

- They can read a rhythm pattern without falling apart two measures in.

- They don’t ask, “Is this right?” after every attempt because sometimes, it is right.

- They look a little less panicked in rehearsal and occasionally even curious.

Teachers will notice:

- The kid who used to fake-play actually makes sound.

- They’ll attempt a tricky passage instead of shutting down.

- Section leaders aren’t handholding them on every entrance.

- Instead of staring blankly, they’re engaged when you rehearse details.

When the above clicks, the student feels fluent enough to fully participate in rehearsal.

What a Fluency-Driven Rehearsal Looks Like

Fluent rehearsals don’t feel “harder.” They feel calmer and more focused. Less survival mode, more forward motion.

A flute player used to stop playing every time she made a mistake. One day, she missed a note, kept going and then raised her hand and said, “Can I do that again?” We all paused. That was her hump. She felt safe enough to try and strong enough to want a redo.

It’s not about playing it right. It’s about not getting left behind.

Here’s what that climb can actually look like.

Weeks 1–2: Finding Sound

Forget the concert. Focus on tone. Daily breathing, long tones, posture checks.

Literally, “How do I make a sound that doesn’t scare the dog?” That’s the first goal. If your beginning clarinets sound like a pterodactyl, build tone exercises into every warm-up until the bad tone is extinct (see what I did there?).

Teach how to practice during class — show them what repetition looks and sounds like. Dr. Elizabeth A.H. Green, author of “Practicing Successfully: A Masterclass in the Musical Art,” puts it simply: “Practicing is an adult activity.” Kids want to run full speed ahead … and the monotonous repetition of practice puts the brakes on this. Any variety you can add is key.

Kids don’t know what “go work on this” actually means. You have to model the methods for them.

Weeks 3–4: Building Control

Add rhythm patterns over long tones. Call-and-response drills: You play, they echo. Begin short excerpts of concert music — just a few bars at a time.

I used to skip this part. I’d go from scales straight into the music and wonder why everything fell apart. Once I started treating rhythm like a language instead of a side skill, things changed.

And yes, sometimes they still clap the wrong beat, but now they know it’s wrong. That’s progress.

Weeks 5–6: Fluency and Connection

Ask questions: “Why are we playing this scale?” Sit in the silence — give them time to discover that this scale is the same key as their piece.

If you have access to SightReading Factory or even literature to sightread, this is the time to begin putting new music in front of students. Start at their grade level or a half grade level down. If they are brand new, keep it short — just two to four bars. A win is a win, and the great thing about music is that we can also keep building up.

By now, students should be starting to feel capable. When they do, discipline gets easier. Both the discipline to work consistently at something, and classroom behavior and engagements.

Connect the Dots (Loudly. Literally.)

Kids don’t automatically understand that your warm-ups are connected to the music. You have to say it out loud, even when it feels silly.

Seriously, be dramatic. “Wait … our warm-up had F-naturals, and so does this piece?! HOLY CATS.”

You’ll get some eye-rolls, a few laughs and a handful of lightbulb faces. Even if 99% of your kids get it, that 1% needed this.

Your job isn’t just to teach them notes. It’s to show them how this stuff connects.

Side note: Sometimes, I’ll stop rehearsal just to say, “This is the same rhythm we just clapped.” And they’ll say, “Ohhhhh.” (Like it wasn’t on the board the whole time.)

A Practical Routine That Builds to the Hump

If you have 45 minutes, here’s one way to structure the climb every day:

| TIME | FOCUS | WHAT IT LOOKS LIKE | WHY IT MATTERS |

| 0:00–0:05 | Tone & Air | Breathing, long tones, unison chorales | Start with sound. Always. |

| 0:05–0:15 | Technique | Scales and flexibility in the concert key | Directly applicable to your piece. Piece is in Bb? Play a Bb scale. Piece is in Db? Pick a different piece. (I’m kidding— kind of). |

| 0:15–0:25 | Rhythm & Literacy | Rhythm drills, call-and-response, simple reads | Pulse + clarity = confidence |

| 0:25–0:40 | Repertoire | Apply those skills directly to your concert music | “That warm-up scale? That’s measure 47!” |

| 0:40–0:45 | Reflection | Quick recap or goal for tomorrow | End with purpose, not frustration |

The key here is flow. These aren’t disconnected exercises — they’re steps in one long skill chain. Warm-ups serve the technique. Technique feeds the piece. It all loops back to fluency.

And if something goes off the rails? You adjust. I’ve had days where the “quick recap” turns into a 10-minute group sigh — that’s okay. Sometimes the climb pauses. Just make sure it doesn’t stop.

Use Compound Lifts (Then Back Off and Isolate)

In strength training, a compound lift is an exercise that hits multiple muscles at once. So, you could work out and do some dumbbell flyers and cable crossovers to hit your pectoralis major and minor, and then some front dumbbell raises and seated machine shoulder presses to work the shoulders, overhead dumbbell extensions and skull crushers with an EZ curl bar for your triceps. Then, you could move to the stabilizing and supporting muscles with scapular push-ups, wrist curls, farmer’s carries, planks and Pallof presses.

Or, you could just do a bench press and hit them all.

For the time-strapped teacher, thinking in terms of “compound lifts” can really help you cover multiple concepts at once with one exercise.

Example: The articulation study on page 3 of “Foundations for Superior Performance” is a Swiss army knife.

- Use it to work articulation

- Layer in tuning (unison or chords)

- Add balance layers (pyramid, reverse pyramid, mid-voice lead)

- Isolate rhythm (have students chant or clap it first)

Also, just because it says “concert F” doesn’t mean you can’t do it in E-flat or B or C#. You’re in charge.

But isolate when needed. If you’re working rhythm, just focus on rhythm. Don’t correct the note or comment on tone. Let kids focus. (This will be harder for you than them!) Then layer more later.

Show Students What Progress Looks Like

If a student improves, tell them how. Be specific.

“That run was clean because you’ve played that scale every day for two weeks, and your fingers went down at exactly the right time.”

“You clapped that rhythm perfectly. That’s the same one from Tuesday’s warm-up. You used to rush it, but now you are putting the perfect amount of space between the two quarter notes.”

They won’t always see the connection. Your job is to draw the line and say it out loud.

Eventually, they’ll start drawing their own lines. When that happens, class doesn’t feel like a bunch of separate exercises. It feels cohesive.

A Few Don’ts

Just in case you needed permission …

- Don’t just rehearse the ensemble as a whole. Listen to sections and individuals.

- Don’t warm up in F, play a piece in Eb and wonder why it didn’t apply.

- Don’t assume students know why they’re doing something. Tell them.

- Don’t fill time just to say you taught bell-to-bell. Purposeful beats busy.

And finally: Don’t forget to always play. Always sing.

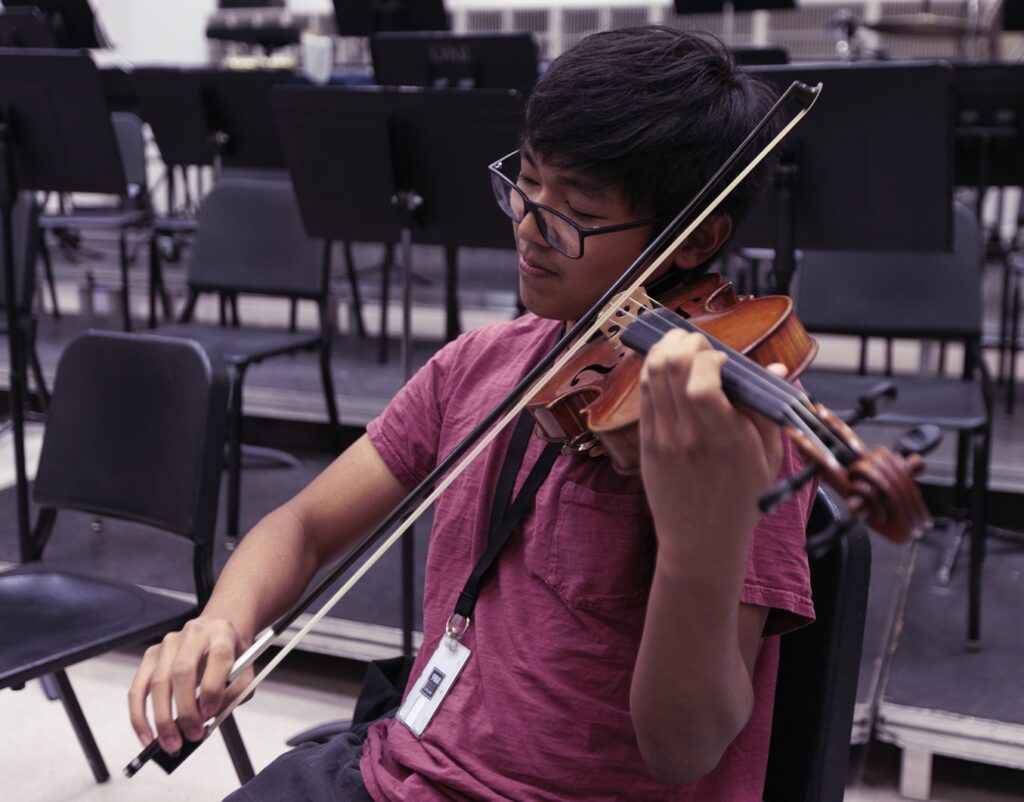

If kids are playing, they’re not talking. If they’re singing, they’re engaged. Keep them moving. (I know you’re now picturing the violinist or percussionist who is talking while playing … just suspend your disbelief for a moment, OK?)

This Is the Tired That Feels Worth It

Teaching this way isn’t easy. It takes planning and energy. You’ll leave the room tired, but it’s a good tired that makes students and teachers proud.

You can’t control their practice time outside of school. You can’t control if they take their instruments home. But you can control your rehearsal time.

Most kids don’t need more motivation. They need to feel like they’re not bad at it. And when they do, they’ll stay.