Tagged Under:

Bridge the Gap Between “Knowing” and “Doing”

Try these practice strategies to help students move from listening to information and implementing it.

Every band director struggles to find strategies to bridge the gap between providing information to students and getting them to achieve the desired result. How do you get students to actually do what they have been told to do?

Below are some ensemble and practice strategies that I use to help students listen to the information and implement it. Some of it begins with students buying into what they are doing and believing in it. A lot of it is assisting students realize how much it takes — physically and mentally — to achieve great music-making.

Move from Conceptualizing to Actualizing

Many of the band members at Claudia Taylor Johnson High School are masters of the “essay test.” They can take a topic and often regurgitate all the information they’ve ever heard about it to hopefully hit a homerun somewhere in there.

In music, the performance is the essay, and students knowing what to do and doing it are two very different things. The knowledge often doesn’t translate. How beautifully and musically our students play hinges on their ability to move from conceptualizing to actualizing, and the gap often appears in the results of their performances. For example:

In music, the performance is the essay, and students knowing what to do and doing it are two very different things. The knowledge often doesn’t translate. How beautifully and musically our students play hinges on their ability to move from conceptualizing to actualizing, and the gap often appears in the results of their performances. For example:

- Students know it takes practice to be great, but they don’t always practice.

- Students know they should listen to their neighbor and match, but they don’t always remember to do it.

- Students know they should play with their best sound, but they don’t always know how to take what they have been told and physically achieve it. Or, what they hear sitting on one end of the instrument is different than what their director hears on the other end.

- Brass students know they should “keep their eyebrows out of their lip slurs,” but they’ll do just about anything to move from pitch to pitch when things get stressful.

- Woodwinds know they should have newer, quality reeds for their instruments, but they enjoy re-living the taste of those enchiladas from last Tuesday far more than they can fathom breaking in a new reed.

- And of course, all band members know they should not throw a football around inside the band hall, but … well, you get the point.

Sometimes students make choices. Sometimes students are lazy. More often than not, when it comes to making beautiful music, students either forget what they have heard or have to remember the correct information — in other words, they struggle to bridge the gap between “knowing” and “doing.”

Listening Skills and Self-Awareness are Learned Skills

A big piece of connecting knowing and doing is to develop students’ awareness. We ask students to listen and “use their ears,” but sometimes the results still fall short.

Guiding students to listen beyond their ears and react to certain stimuli is no different than training students to form an embouchure or take a proper breath. In other words, provide clear information to students, have them practice, give them feedback — then repeat. Keep in mind that students will only fix what bothers them. Until they are as bothered by a problem as their coach, they will be limited in the amount they can improve.

Guiding students to listen beyond their ears and react to certain stimuli is no different than training students to form an embouchure or take a proper breath. In other words, provide clear information to students, have them practice, give them feedback — then repeat. Keep in mind that students will only fix what bothers them. Until they are as bothered by a problem as their coach, they will be limited in the amount they can improve.

So, how do you transition listening skills into learned skills?

- Constantly reinforce that students should have an opinion. After a musical segment during rehearsal, after a performance or after listening to anything, ask students what they think about what they heard.

- Ask simple questions like: “Should they play long or short?” or “Should they play smooth and connected or more detached?” Then follow up by asking them “why” to jumpstart conversations.

- Eventually, you can move into more advanced questions, such as: “What did you think about the clarity of the tone quality?” or “What did you think about the consistency of style?” or “What did you notice about that phrase ending?”

“I Don’t Know” is an Acceptable Answer

Train your students to respond in one of three ways: “Yes, I think so,” “No, I don’t think so” or “I don’t know” — which may sound surprising.

Train your students to respond in one of three ways: “Yes, I think so,” “No, I don’t think so” or “I don’t know” — which may sound surprising.

One of our brass instructors, Joe Dixon, tells students that he had a former teacher who questioned him about some things in his playing. “My teacher complimented many aspects of my playing then told me to listen carefully to the end of one of the notes,” Dixon says. “I shared that I could not hear what he was talking about, and he responded, ‘That’s OK, just remember I said it.’”

This story resonated with our students in helping them learn to distinguish between what they can or cannot hear, as well as helping them hear what we do to improve their playing.

Knowing that a note should be performed with a particular style or length and hearing if it is happening hinges on a student’s ability to recognize the difference.

Students Must Learn to React Without a Director

In our program, we spend time in smaller group sectionals identifying “out-of-tune” versus “in-tune” unisons, which sounds like a single player on an instrument. We each have different ways of approaching “in tone, in tune, in time,” but getting each student to react centers on the director’s ability to develop reactions from the performers.

Earlier in my career, my students reacted to problems by reading the expressions on my face or, worse, when I would yell during rehearsal. I was surprised to learn that most of the time, students did not hear what I was angry about but only tried harder when they sensed the energy in the room getting more intense. Developing critical listening skills has resulted in students fixing and reacting to things faster — before I get frustrated.

Questions to consider to help students develop critical listening skills:

- How can students tell if it’s out of tune?

- How can they hear if it’s out of time?

- Are they only reacting to what you do?

Students Must Have Listening Role Models

Tell students to have three role models on their instrument. Provide examples for students who are unsure of which artists to listen to.

Ask students to identify and write about one piece per musician, what they hear and what they like. Ask students to compare their sounds to the professional.

Fundamental vs. Musical Issues

Our clarinet teacher, Philip May, regularly tells our students that there are two distinct challenges they face as musicians: 1) how well they play their instrument and 2) how well they play the music.

Although the two share similarities, May’s point is that students need to invest as much time and attention to mastering their instruments as they do to learning the music for band rehearsal. Students who have better control over their instruments will have more skills to perform music at a higher level. One of the fastest ways we help our students improve their playing is connected to their breathing.

Breathing to Play vs. Breathing to Live

Breathing to Play vs. Breathing to Live

Periodically, we ask our students, “Why do we practice breathing exercises?” As you can imagine, we receive a colorful assortment of answers ranging from the bizarre to the sublime: “To learn to take a full breath,” “So we can sound good on our instruments,” “So we can play longer phrases,” “So we know how to breathe in music” and, my personal pet peeve, the blank stare.

How many of us spend a few minutes each day during warm-ups working on how to take the proper breath to produce the most characteristic sound only to get into the music and find that students aren’t breathing properly? Just watch young players during their breathing exercises and then see what they do while playing — you’ll be surprised at the variety of breathing methods. Some students breathe correctly, others maybe not at all, and some fall somewhere in between.

In the article, “Improve Student’s Tone,” I discuss how our ultimate purpose in practicing breathing with our students is so they “remember to do it when they get to the music.” One of my mentors, Tom Bennett, who was the director of bands at the University of Houston, guided my focus early in my career to understand the difference between a “playing” breath and a “living” breath. The type of breath students use when sitting (not playing), walking to class or hanging out is entirely different from the type of more athletic breath needed to produce a characteristic sound.

Students must practice “playing” breath exercises in class, so that when they get into the music, they know how it should feel. Most students will revert to taking “living” breaths, especially before they play after a silence. Train students to take a type of “replacement” breath during these transition times.

We teach the concept of “phrase breathing” versus “catch/replacement breaths.” A phrase breath would be in between longer musical phrases and might occur in unison across the ensemble, whereas a catch/replacement breath is quicker and should minimally disrupt the phrase. Students should plan catch/replacement breaths in a way that you can’t tell when they are entering and exiting, also known as “stagger breathing.” A catch/replacement breath must happen quickly and should not affect the tempo of the music, whereas a student or ensemble may slow down or speed up coming in and out of a phrase breath.

Training students on a few breathing rules can make a difference in the quality of sound during performances, but only if they actually follow through with those rules. To get the rules’ fundamental message across to students requires some rephrasing and training.

Rule: Students should avoid breathing in predictable places such as at bar lines.

Rule: Students should avoid breathing in predictable places such as at bar lines.- Bridge the gap: Ask students to mark where they will breathe instead, then practice this breathing plan with them in context.

- Rule: Students should avoid breathing at the end of a crescendo.

- Bridge the gap: Practice the music before, during and after the crescendo, training students to breathe in the middle of the crescendo or in another section.

- Rule: Students should avoid breathing before rhythmic activity.

- Bridge the gap: Train students to avoid breathing before music becomes more rhythmically active, i.e., before 16th note or triplet rhythm that they may subconsciously want to “tank up” and create holes in the sound/phrase.

- Rule: Students should work to stagger breaths with students around them and not breathe when their neighbor does.

- Bridge the gap: Ask students to perform the segment and listen to see if there are “holes in the sound.”

Remember, students want to do what is most comfortable, and “breathing to play” is rarely comfortable. You must provide students with information, as well as reinforce proper “playing” breath techniques to bridge the gap between knowing and doing.

Other Bridge-the-Gap Strategies

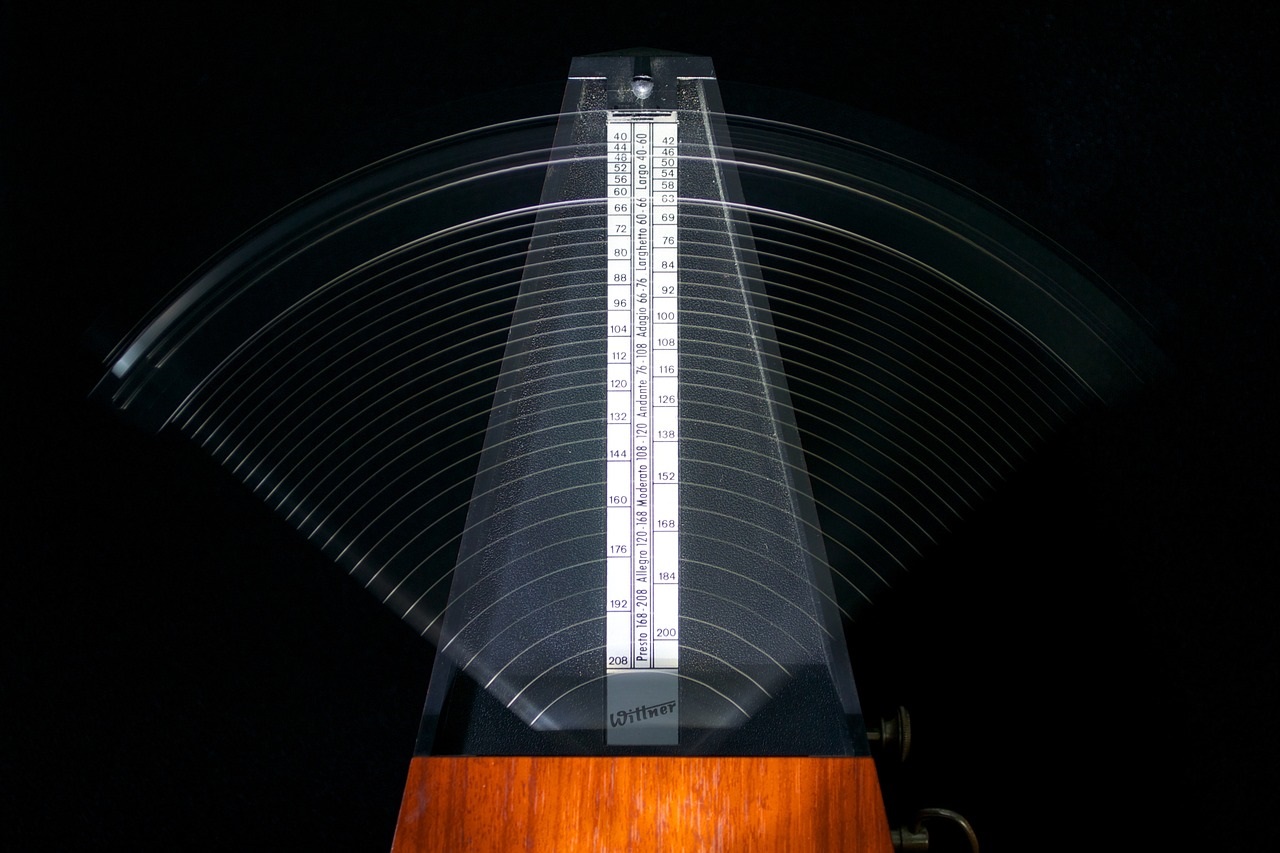

“Help us help you” — We use this phrase often because we want students to learn to self-advocate or come to rehearsals prepared so they can be successful. The students at CTJ require daily reminders to use tuners or metronomes in individual practice, as well as to bring pencils or highlights to rehearsals.

“Hold up your pencils and highlighters” — For many years, Emily Gurwitz, the band director at one of our feeders, Bradley Middle School, would begin each rehearsal by asking students to “hold up your pencils and highlighters.” No rehearsal began without this step, and students could not rehearse without them. The result? Students had pencils and highlighters during rehearsals as needed. This habit, formed early, transferred to high school, and students were more likely to show up to rehearsals with a pencil and a highlighter. What seems like a simple process that took only a few seconds each day required persistence on Gurwitz’s part. She is now a band director at Judson High School in San Antonio, where she still begins her rehearsals with this timeless tradition.

Accountability strategies

- Practice records with focuses rather than just minutes on the instrument.

- Use pass-off or star charts. Consider breaking the music down into chunks that students must “play-off” for a director, student teacher or even a student leader. List all of the students’ names on a chart going down the left side and the chunks of music going across the top. As the student passes-off the segment, they get to put a sticker under that segment next to their name so other students can see everyone’s progress. This incentivizes students to pass-off their music so their peers see that they are working hard.

- Utilize software to break down assignments into smaller steps. Programs like SmartMusic and MusicFirst help students practice music with the computer for instant feedback. Consider minimum score requirements before students can submit an assignment.

- Regularly check woodwind reeds during band rehearsals or sectionals by asking students to hold up extra/replacement reeds that they have on hand.

Structure practice for students

- Provide students with exercises specifically to help improve their playing so they can achieve music.

- Teach students ways to improve technique like utilizing broken rhythms, metronome games or practicing tonguing slurred notes passages (or slurring tongued note passages).

- Introduce brass players to pitch bends and coach them on how they can improve their ability to move gracefully from note to note.

- Emphasize the importance of students recording themselves and listening back, show them how to do this or what software to use.

Tuners and metronomes

Tuners and metronomes

- Teach students how to properly use tuners and metronomes.

- Define the parameters and purposes for these tools.

- Show students specifically how you expect them to use tuners and metronomes

- Teach them that sometimes it can get worse to use a metronome before it gets better.

Tackle Issues Individually … Literally

Another of my mentors, Dr. Lawrence Markiewicz, director of bands at Independence (Kansas) Community College, taught drum corps for many years before moving to the collegiate level. He is a master at bringing out the highest level of performance from his students. His hornlines at the Cadets and Glassmen were remarkable for their musicality, energy and clarity.

One of his primary strategies to achieve clarity was the individual performances “down the line,” where students would play passages of music for feedback and sometimes accountability purposes. Markiewicz believed that by getting into the weeds and listening to students individually, he could better diagnose articulation or technique problems. Students could hear better when they played individually. They would also become more aware of things as they listened to others perform. While the technique can be stressful for students, maintaining a positive environment and having students play by themselves frequently can alleviate that anxiety and result in rapid improvement.

The same applies to “group rhythm counting” — ask students to individually count rhythms aloud during rehearsal to eliminate rhythm problem. Students learn how things sound by listening to their neighbors rather than just reading the music on the page. Helping students learn to function and react independently can only help them improve.

Tying it All Together

Our end goal is for our students to learn to listen like professional musicians to create and experience music at the highest level. Students who understand how to connect the dots stand a far greater chance of enjoying magical musical moments early in their journeys that can propel them to continue to play for the rest of their lives.

We understand that not all our students will pursue a career in music, but we want them all to have the tools to be successful performers in any capacity. By developing their performance and listening skills, we hope they will be more apt to continue performing beyond their days at Claudia Taylor Johnson High School.