Apply Music Learning Theory Principles in Your Teaching

Teach young children to use all their senses to engage and learn about music.

The beloved television icon, Mr. Rogers said, “Play is often talked about as if it were a relief from serious learning. But for children, play is serious learning. Play is really the work of childhood.” (Heidi Moore, “Why Play is the Work of Childhood,” Fred Rogers Center, 2014.)

I would venture to guess that we all know that young children actively use all their senses to engage with and learn about the world around them — my 11-month-old puts everything in her mouth for that exact reason. But how do we transfer that idea to the piano lesson?

What is Music Learning Theory?

I first became familiar with Music Learning Theory in graduate school at the University of South Carolina. I used the Music Play curriculum to play with children age 5 and under. One of the students who really helped me grow as a human, a musician and a teacher was a boy named Anthony who has autism (pictured to the right). Through my lessons with Anthony, I learned to really listen and react to the musical responses of each child, and I learned to improvise and create my own music based on these responses.

I first became familiar with Music Learning Theory in graduate school at the University of South Carolina. I used the Music Play curriculum to play with children age 5 and under. One of the students who really helped me grow as a human, a musician and a teacher was a boy named Anthony who has autism (pictured to the right). Through my lessons with Anthony, I learned to really listen and react to the musical responses of each child, and I learned to improvise and create my own music based on these responses.

Quite simply put, Music Learning Theory tells us how children learn when they are learning music. Through years of research, Dr. Edwin E. Gordon discovered that we learn music in the same way we learn language and that the best way to develop musical potential (which everyone has!) is through active participation: singing, listening, moving, playing, imitating and creating.

Sidenote: Victor Wooten has a wonderful TED Talk about Music as a Language.

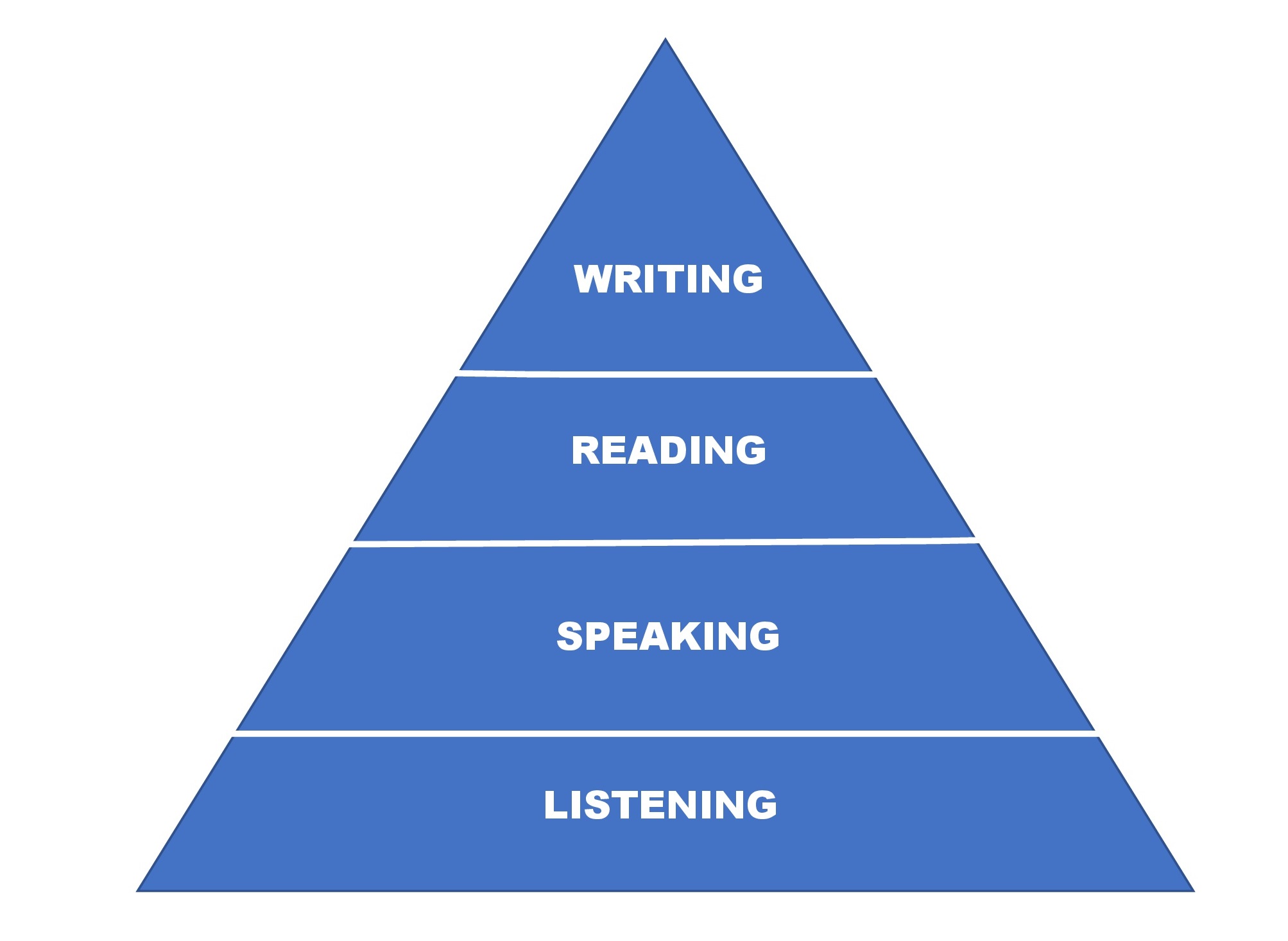

Let’s think about how children learn language. First, they absorb through listening then they babble — nonsense syllables at first and then slowly, through imitation, a real word or two start to emerge. Even when the sounds are unclear, adults or older children give clarity and meaning to those words. Words turn into sentences, and soon, the child is thinking fully through language and holding conversations with other people. After years of practicing how to listen and talk, we then teach the child how to read and write.

Let’s think about how children learn language. First, they absorb through listening then they babble — nonsense syllables at first and then slowly, through imitation, a real word or two start to emerge. Even when the sounds are unclear, adults or older children give clarity and meaning to those words. Words turn into sentences, and soon, the child is thinking fully through language and holding conversations with other people. After years of practicing how to listen and talk, we then teach the child how to read and write.

We all know the educational guide, “Sound Before Symbol” by Maria Kay. Unfortunately, in music lessons, teachers often rely on a method book to guide the structure and curriculum of a child’s musical journey, thus skipping several steps in the learning process.

Listening

I always use 3/4 meter as an example of what can happen if a child does not have a firm listening foundation. Most songs played on the radio are in 2/4 or 4/4 time, so students generally know the feel of these meters. However, I’m sure you’ve had students who dropped or added a beat in 3/4 without noticing that anything was wrong. Just as young babies learn the natural inflection of their birth language(s), children (and adults) learn their musical language and the natural inflection of a style, meter or composer through listening before trying to play.

During the listening stage, I play patterns or small groups of notes for my students and ask them to identify if my two patterns are the same or different. There is a Music Learning Theory saying: “We know what something is by knowing what it’s not.” (Edwin E. Gordon, “Learning Sequences in Music: Skill, Content, and Patterns,” Chicago: GIA Publications, 2003.)

If the student cannot identify that a pattern in 3/4 sounds different than a pattern in 4/4, they are not ready to move on in the learning sequence.

Movement

I challenge you to listen to any upbeat song by the Beach Boys, Beatles or BTS and try not to move. It’s impossible! And that’s a good thing. Music and movement are meant to be intertwined. I write about this in more detail in “Use Movement to Fix Rhythm,” but I will give an example here.

After my students have listened to many songs in 3/4 meter, I invite them to move while I play a piece in 3/4. If they can keep the macrobeat and microbeats steady, I know that they are audiating in the meter. If they cannot, then I know that they need more time listening.

Improvisation

Next, I give my students a chance to babble or talk on their own and improvise at the piano in 3/4 meter. I will keep the parameters simple: Put both hands on a D pentascale and improvise a piece in 3/4. I usually allow students to play on their own before I add an accompaniment pattern. Again, if my students stay in 3/4, I know they understand and are audiating triple meter. If they are struggling to play with consistent macro- and microbeats, we will spend more time listening and moving.

Next, I give my students a chance to babble or talk on their own and improvise at the piano in 3/4 meter. I will keep the parameters simple: Put both hands on a D pentascale and improvise a piece in 3/4. I usually allow students to play on their own before I add an accompaniment pattern. Again, if my students stay in 3/4, I know they understand and are audiating triple meter. If they are struggling to play with consistent macro- and microbeats, we will spend more time listening and moving.

At this time, I also revisit the same/different game, but now I allow students to be the teacher and ask them to create patterns. Then I will identify if they are the same or different. (Students always love a chance to reverse roles!)

Reading

Depending on the student, I may do some rote, or imitation, teaching before we move on to reading notation. When I transfer to notation, I again go back to my patterns and teach the notes and rhythms in relationship to each other and the keyboard, rather than just focusing on the note or rhythmic value names — see my article, “Note-Naming ≠ Music-Reading.”

Most method books introduce a half note as getting two counts. However, knowing that a half note gets two counts in some meters is a different skill from knowing what that half note will sound like in context.

I believe it is our responsibility to create musicians, not just great piano technicians. Through the tenets of Music Learning Theory, children and adults can expand their musical horizons and come much closer to reaching their full musical potential.

Music Learning Theory reminds me of this famous quote that has been credited to Benjamin Franklin: “Tell me and I forget. Teach me and I may remember. Involve me and I learn.”