Tagged Under:

We’re Not Here Only for the “Good” Kids

Don’t lower the bar to have an inclusive program, just be patient and hold open the door a little longer for some students.

Some students just know how to “do school.” You know the type — folders organized, pencil always sharpened, head nodding right on cue during rehearsal instructions. If we’re being honest, most music programs are built around these kids. They are easy to teach. They follow directions. They say thank you.

They don’t complain when things don’t go their way. They show up on time. They sit where they’re told. And most of the time, they would’ve done all these things for any teacher — not just you.

A colleague once said that the “good” kids are the ones who don’t need you all that much.

They’re already wired to comply, already on track to succeed — and honestly, it feels nice to ride that wave. These students are satisfying to teach. You give an instruction, and they actually follow it. No pushback. No side comments. No drama.

But what happens when we start shaping our programs only for these kids? What happens to the rest of the students?

Don’t Write Them Off

A few years ago, that same colleague had a freshman — let’s call him Jay — in a beginning class. Jay was a regular in the dean’s office. It got to the point that the director wasn’t surprised when Jay was missing from band. They just assumed he was “being dealt with.”

When Jay did show up, it was hit or miss. Sometimes he’d play; sometimes he’d sit there. He once told the director that he forgot how to hold “the thing” — the thing being a baritone that he’d been playing for two months. My colleague admitted that they had mentally wrote off Jay.

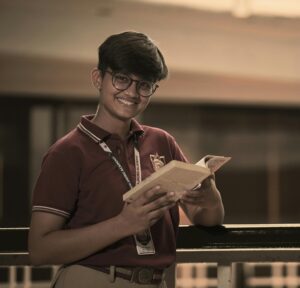

Then one day, Jay started showing up. Not only was he there, but he was … engaged? Playing the right notes? He started helping the kid next to him finger a low concert D. The director asked another student what changed. They said Jay got moved out of a certain lunch group and wasn’t in “trouble” anymore. That was it. A schedule change. No deep intervention or a profound epiphany — just a structural shift.

Jay’s still in band. He’s a senior now, and he’s one of the strongest low brass players that program has. And he was almost missed.

Who’s Succeeding and Why?

Take a snapshot of your top groups — the jazz band, the auditioned wind ensemble, the kids who get solos — and look at who’s in them. Why are those students succeeding in the program?

If the answer is because they show up, do their part and cause minimal problems — great. But we also must ask if our program’s structure allows for anyone else to succeed. Are our auditions designed in a way that filters out a kid like Jay before he ever has a chance? Is “good behavior” an unspoken prerequisite to opportunity?

Here’s the truth: Those “easy” students are already doing the things we want. They say yes to adult authority without needing much from us in return. They don’t test the system. And for a lot of them, they would have found success in any classroom — music or not.

Now, let’s flip that. What about the students who don’t automatically comply? The ones who need you to show up first? The ones who make it clear that trust isn’t free, and it definitely won’t be earned just because you’re the teacher?

Those are the students we build real teaching around. They’re not always comfortable to teach, and they may never say thank you (some may say other things to you … ask me how I know!). When these students succeed — and they can — it’s not because they already knew how to succeed. It’s because we didn’t give up.

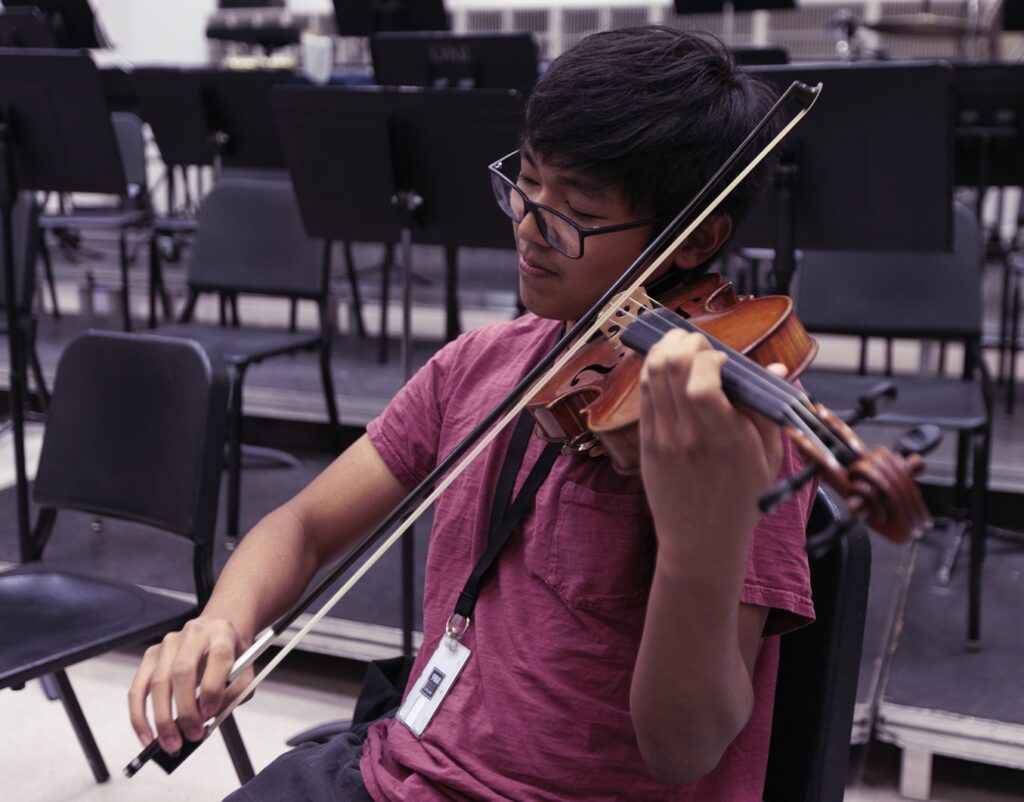

Some kids are late to everything — developmentally, behaviorally, socially. That doesn’t mean they can’t become incredible musicians. It just means we need to keep the door open long enough for them to walk through it.

Your Routines Should Be a Welcome Mat, Not a Filter

We all love routines. Bell-to-bell engagement. Clear expectations. Procedures for everything from putting instruments away to asking to go to the bathroom. These things matter — they protect rehearsal time and help the group move forward.

However, sometimes our systems accidentally become filters. The kid who doesn’t bring a pencil three days in a row? They’re “unreliable.” The one who shows up late because he’s watching younger siblings? “Disrespectful.” Before long, these students are labeled as a disruption and are slowly pushed out of the experience.

A colleague wondered aloud: What if their routines were built with those kids in mind? What if instead of punishing the missed pencil, they had a stash ready without fanfare? What if they let the kid with sibling duty come in late and still play?

This isn’t about lowering expectations. It’s about not letting your binder system be more important than the kid who forgot his binder.

Inclusion Doesn’t Lower the Bar — It Redefines It

There’s this fear — and my colleague has definitely felt it — that making space for struggling students will drag down the whole group. That giving grace becomes a slippery slope to mediocrity.

But the best ensembles my colleague has had weren’t just technically strong. They had students who had every reason not to succeed and still did — and that changed everything.

The goal isn’t to build an ensemble that looks perfect on a poster. It’s to build one that represents the school. The real school — the one with behavioral referrals, missed buses and lunch detentions. An inclusive ensemble doesn’t mean everyone plays first chair. It means there’s a spot for all students — even the ones who came in late, forgot their music and didn’t know the key quite yet.

Yes, some kids need more coaching. Some need a second or third chance. That doesn’t mean they’re getting away with something. It means we’re doing our job.

“Good” and “Bad” Don’t Belong Here

It’s still easy to slip and say it. “He’s a good kid.” “She’s kind of a bad egg.” But what does that even mean?

Usually, “good” just means easy for us. Quiet. Compliant. Timely. The student who turns in forms on the first day. The one whose parents always email back.

Meanwhile, “bad” might just mean the kid doesn’t trust adults yet. Or they’re exhausted. Or they’ve learned that being invisible is safer than being seen.

Band is one of the few classes where you actually get to watch kids grow over four years — and sometimes outgrow the labels they started with. Let’s not do the sorting ourselves.

So, Who’s Missing?

My colleague still thinks about Jay a lot.

Not just because he turned into a solid musician, but because they nearly missed what he could become. They looked at the behavior and forgot to look at the person.

If you feel a little guilty reading this, that’s probably a sign you’ve still got your head on straight. That means you’re thinking about who’s missing from your room, and why.

Let’s make sure the way we run our programs doesn’t accidentally tell some students they don’t belong. You don’t have to lower the bar — you just have to hold the door open.