Tagged Under:

The Creative Repertoire Initiative

A group of 11 composers and a conductor joined forces to create and promote adaptable music to meet the challenges facing music educators today.

Seemingly overnight in March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic swept through our world, leaving us isolated at home and plagued with fear and uncertainty about the future. Jobs lost, businesses shuttered, classrooms moved online — our entire way of life changed in ways that shocked us. And for music lovers, an unthinkable thing happened — live music stopped.

Introspection

Introspection

In early April while still adjusting to a new normal, I received a call from my friend Allan McMurray, director of bands emeritus at the University of Colorado. After we exchanged pleasantries, our conversation turned to the pandemic and its potential impact on school music programs. Allan pointed out the possibility that schools would be mandated to limit the number of students in a rehearsal room to eight or 10 students, perhaps even fewer if wind playing or singing were involved.

Allan said, “If the teachers don’t have music that adapts to this kind of situation, how will they keep their students engaged? Kids might become disillusioned or bored and drop music. Programs could be decimated, and it could take years for some to recover. Some may never recover! What are you going to do to help?”

These were strong words from someone I have known and respected for decades. I took Allan’s call to action very seriously. For days, I pondered his question, unsure of how I could help. As the seriousness of the situation began to sink in, I came to formulate a solution to Allan’s challenge: I began making arrangements of my music that were playable by ensembles of any size or makeup. I resolved to put together a group of composers to join me. I also enlisted conductor Robert Ambrose, a strong advocate of both composers and school band programs. He and I immediately began calling composer friends around the country to ask if they would join us in this mission.

No arm-twisting was required to enlist allies. The 10 composers Robert and I called jumped on board immediately, offering their time and talents without understanding fully what they were getting themselves into — they just wanted to help.

A Collaboration of Composers and a Conductor

That is how the Creative Repertoire Initiative (CRI) was born. We are a collective of 11 composers and a conductor, all committed to the creation and promotion of adaptable music to meet the serious challenges facing music educators in the coming academic year and beyond.

Creative Repertoire Initiative MembersRobert Ambrose, Brian Balmages, Steven Bryant, Michael Daugherty, Julie Giroux, John Mackey, Peter Meechan, Jennifer Jolley, Alex Shapiro, Omar Thomas, Frank Ticheli and Eric Whitacre |

After a series of brainstorming sessions, we settled on a two-fold mission: 1) to create “adaptable” pieces, either arrangements of current works or new compositions, that could be performed in virtually any situation, and 2) to inspire, empower, guide and amplify the voices of other composers who wished to do the same.

Over time, we defined “adaptable” as an umbrella term that encompassed a variety of compositions intended for ensembles faced with limited, fluctuating or unpredictable personnel. We discussed a wide assortment of compositional techniques, including works that utilize electro-acoustics, found instruments and elements of chance. While we recognize that there are countless types of adaptable music, the pieces that CRI composers have created fall into the four categories detailed below.

Adaptable Music Type 1: FLEX

Flex pieces — where instruments are assigned to specific parts based on range/registration — have been in existence for many years. They are suitable for smaller bands where certain instruments are not represented; however, they do require that a minimum of one musician be available for each part in order to be fully realized. So, for instance, if there is no bass range player in the room, then the bass part isn’t performed. Flex pieces are abundant and include those published by Hal Leonard in their FlexBand series, as well as Bravo Music and its Japanese parent company, Brain Music.

Examples of recent flex pieces include:

- John Mackey’s “Let Me Be Frank with You,”

- Michael Daugherty’s setting of Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land” for young players, entitled “Made for You and Me: Inspired by Woody Guthrie,”

- Julie Giroux’s arrangement of her “Hymn to the Innocent” and

- Eric Whitacre’s arrangement of “You and Me.”

Adaptable Music Type 2: FULL-FLEX

These pieces offer maximum flexibility in which any voice is playable by any instrument making a fully realized performance possible with any combination of four or more instruments. Full-flex pieces are useful in situations where only flutes are present for rehearsal on one day, trombones on another day and a mix of instruments on yet another day.

The conductor can also experiment with part assignments. For example, a tuba player can be given part 1 and a flute player part 4, which places the melody in the tuba. This might prove to be a fun experiment — the tuba player might enjoy being able to play the melody virtually the entire time. The full-flex approach was created in direct response to the need for radically adaptable pieces in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Recent examples include:

- My arrangement of “Simple Gifts: Four Shaker Songs,”

- Brian Balmages’ “Colliding Visions,”

- Steven Bryant’s arrangement of “Dusk” and

- Pete Meechan’s “Taking the Fifth.”

Adaptable Music Type 3: MODULAR/CELLULAR

These pieces rely on motivic cells in which one cell may be repeated at will before going on to another cell. A groundbreaking example of modular/cellular music is Terry Riley’s “In C.” Composed in 1964, “In C” can be played by ensembles of virtually any size and makeup. Performers are empowered to choose dynamic levels, the order in which individual cells are played, the number of times they are repeated, etc.

Recent modular/cellular pieces include:

- Jennifer Jolley’s “Sounds from the Gray Goo Sars-CoV-2,”

- Alex Shapiro’s electroacoustic “Passages” and

- My “In C Dorian” (inspired by Terry Riley’s piece and dedicated to him).

Adaptable Music Type 4: IMPROVISATORY

These adaptable works based primarily on improvisation could entail jazz chords, verbal directions, alternative notation and any number of additional ways to provide a framework for improvisation. Omar Thomas’ “Sharp 9” for young musicians is a recent example. Its 12-bar blues serves as an introduction to improvisation while also introducing young ears to rich jazz harmony.

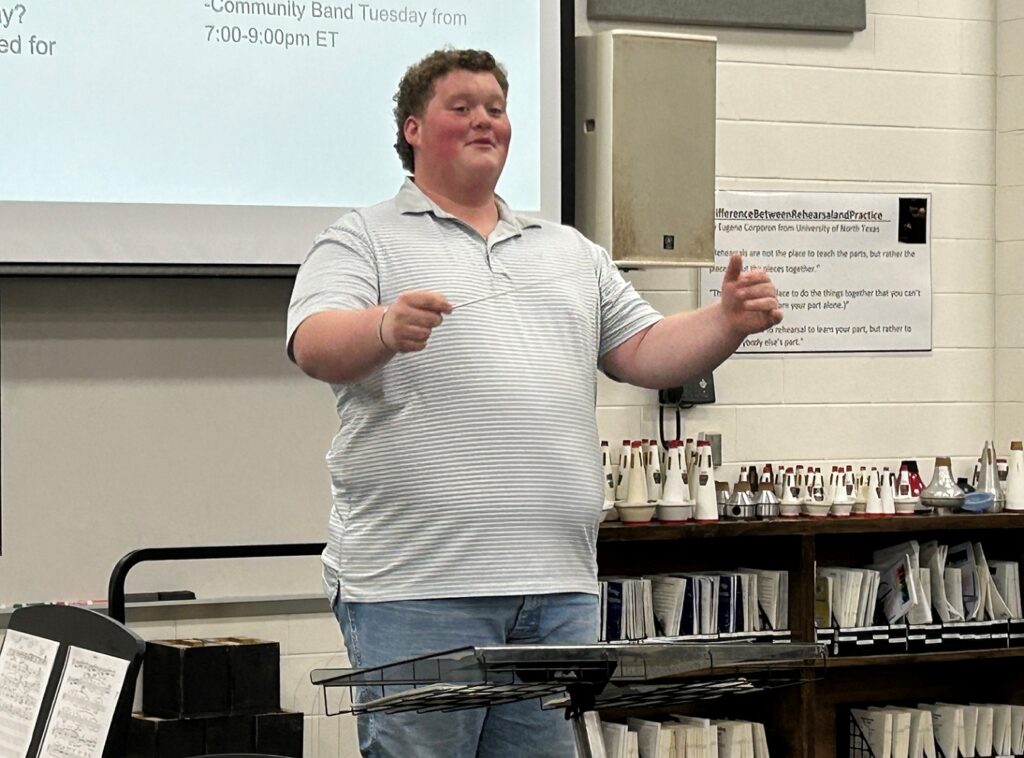

Composer Gatherings

Composer Gatherings

We recognize that crises such as the current pandemic serve as wake-up calls, firing the imaginations of composers, conductors and performers to find new ways to engage in music-making. As we move forward, we hope to learn from others about new ways to enrich this repertoire.

As outlined in our mission statement, CRI is committed to encouraging, guiding and advocating for other composers who wish to create adaptable music. We have done so in myriad ways:

- The CRI website has a composer resource section that contains tutorials, score templates and sample score excerpts for others to use or modify to suit their needs.

- The CRI Facebook group is a place for composers to highlight their adaptable music and for directors to learn about these works.

- CRI hosted two “Adaptable Music Forums” as part of Robert Ambrose’s The Digital Director’s Lounge Zoom show. These forums provided a platform for composers to present their adaptable music to a room of hundreds of educators from around the globe. These invigorating sessions provided hope, inspiration and joy to many. It was particularly heartening to learn about the vast number of composers who devoted their time during the summer months to create adaptable music.

A Network of Support

Adaptable music is available from the usual places music educators and musicians obtain their music: distributors, publishers and self-published composers or their representatives. Scores and parts for adaptable music are most often made available as PDF files, although some publishers also provide sheet music. While there is no single, centralized location where you can obtain adaptable pieces, The Wind Repertory Project has added “Adaptable Instrumentation” and “Flexible Instrumentation” categories to its website, as well as an “Initiatives: Creative Repertoire Initiative” category where adaptable works are listed alphabetically by composer.

While the COVID-19 pandemic served as the catalyst for the immediate creation of adaptable music, we recognize that the very same music may serve a vital purpose long after the pandemic has passed. Small instrumental music programs, college and university conducting classes, and anyone looking for ways to supplement mainstream large ensemble music may find adaptable music a welcome resource.

To all music education professionals, please know that you are not alone. As you face the unprecedented challenges that lie ahead, there is a huge network of professionals who are thinking of you and supporting your work. This includes the many living composers who are excited to artfully expand this greatly needed repertoire. We hope the growing number of adaptable pieces being created offer a path forward in the year to come and beyond.

This article appeared in School Band & Orchestra magazine and ACB Journal.