Tagged Under:

Expansive Music Education

By broadening the scope of musicianship, teachers can introduce and engage more students to pursue all aspects of music-making.

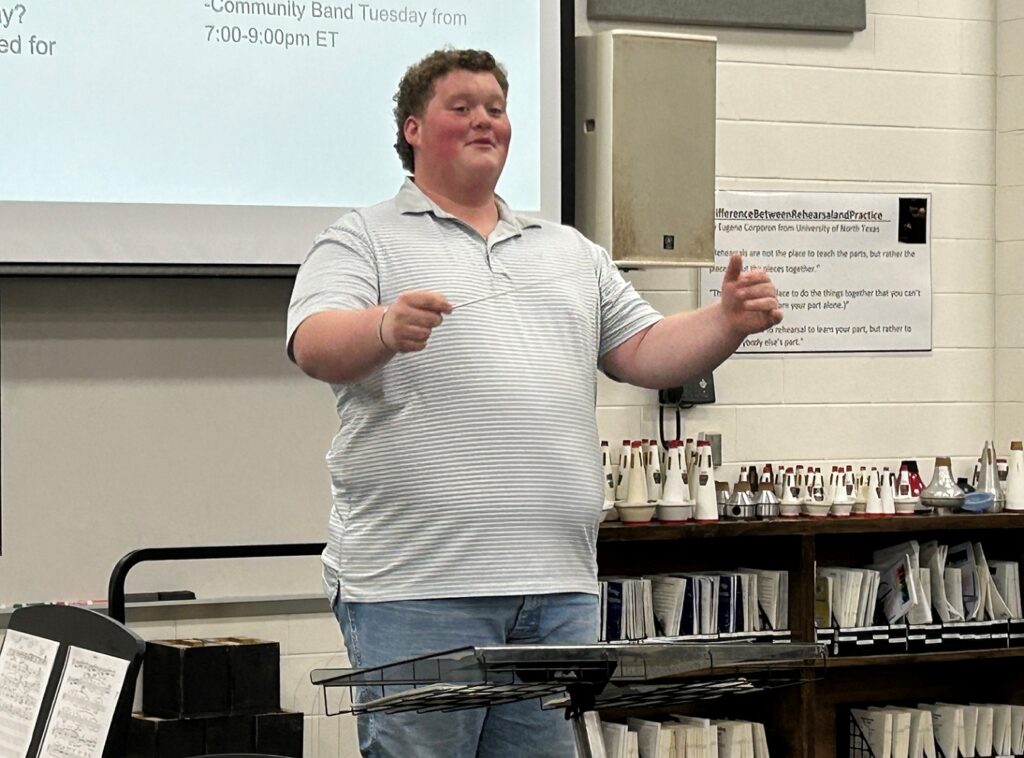

When Marissa Guarriello, Assistant Professor of Strings at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, first took a job in music programming at ArtsQuest, she felt prepared. After all, she had undergraduate and graduate degrees in music education, plus teaching and performance experience.

However, upon starting her new job – which included reviewing musician contracts, working at live performances and facilitating merch sales – Guarriello realized that she had trouble understanding even basic conversations among her coworkers. “The first thing that caught me off-guard was the terminology,” she says. “I had no idea what people were talking about half the time, and it’s stuff pretty specific but basic to the entertainment industry.”

This experience made it clear that even though Guarriello had an education in music, she wasn’t prepared for various on-the-job skills required for assisting in other areas of the music business. Because most music education programs focus on performance, she worries that many students will have a similar experience once they start a job in the music industry.

“You must have a good understanding of what it takes to put on a concert in any setting,” Guarriello says. “It would be a really good idea to have these core concepts worked into our secondary music education.”

Guarriello began promoting expansive music education, which includes introducing students to elements of a concert beyond just the performance itself. Now, she regularly hosts clinics and speaks at conferences about ways educators can incorporate expansive music education into their programs for a richer overall student experience.

Musicking: Expanding the Definition of a Musician

Core to the practice of expansive music education is the theory of “musicking,” a term coined by musician, educator and author Christopher Small that reorients the word “music” from a noun to a verb — to music. Musicking posits that everyone involved in the facilitation of a musical performance is making music.

“When you go to a rock concert, not only are the performers on stage musicians, everyone else is, too” Guarriello says. “The person who bought the talent and cut the deal with agents, the band manager, the bus driver, the people taking tickets — they’re all considered a musician because they’re helping to facilitate this experience successfully.”

Guarriello supports this expansive definition of what is means to make music. She says that broadening the scope of the word “lends a lot of dignity and responsibility to those who act as the facilitators of music.”

Plus, increasing the reach of musicianship provides more educational opportunities for music students, which can better prepare them for a career beyond high school. While most music students will not become full-time professional performers, they may still find a career in another music discipline on the business or organizational side.

Many schools are already expanding their music program’s offerings. “It’s this idea that we’re moving beyond what’s traditional,” Guarriello says. “We’ve always seen general music, band, choir and orchestra. However, in the past decade, there’s been an emergence of guitar, piano classes and modern music, particularly at the secondary level.”

The next step to get more students involved is to introduce a more expansive approach to what it means to be a musician in the first place. Bob Habersat’s article, “Reaching Nontraditional Students,” and Jameyel “J. Dash” Johnson’s “6 Real Ways to Reach the 80%” discuss reaching students who do not participate in traditional school music offerings of band, orchestra and choir — this is the exact sentiment that Guarriello is echoing. “I was not part of the 80% — I was very much in the 20% of students who was involved in traditional school music and loved it, and I still do,” she says. “However, as a teacher, it was evident I wasn’t reaching most students despite what I thought I knew, what I was taught, and what I personally loved. I had to reflect and make changes as a teacher to give my students the best education possible. That reflection and subsequent changes to my class continue every day to make sure I am being as responsive as possible to the learners and musicians sitting in front of me at any given time. Ultimately, that has meant expanding what I offer in my music classroom.”

Theory Meets Practice

While “musicking” is a theory often discussed in music educator circles, teachers also need to find practical approaches to introduce it in their classrooms. Guarriello leads clinics at high schools and presents at conferences about basic music industry topics. “Every time [I speak on the topic], people are shocked,” Guarriello says. “People, including teachers, never quite realize what goes into this side of the industry.”

While working at ArtsQuest, Guarriello’s role focused on booking talent for the venue. She uses this experience, plus others, to introduce both students and teachers to the various roles available. “We’re focusing on live music,” she says. “We break down the basics of the performance: who’s touring with the band, who’s on the venue side. We look at what it looks like to contract and buy talent and where the money goes.”

During Guarriello’s tenure at ArtsQuest, she participated in the creation of Music Industry Day, a field trip for students to see what goes into various elements of a live performance. “Students learn about the media, the marketing, the talent buying, the production,” Guarriello says. “They see just a snippet of what goes on behind the scenes.”

Guarriello also worked on the Musikfest Education and Industry Conference while at ArtsQuest. Like most conferences for music educators, this event featured presentations from teachers on a variety of different topics; the difference was, these presentations focused on elements beyond music performance.

“The goal was [to educate attendees] on how the industry works so they can go back to their classrooms and inform their kids,” Guarriello says.

Attendees learned about diverse topics like songwriting and the impact of artificial intelligence on the music industry. “The first step was to make sure teachers understood the importance of incorporating these topics in their classes and passing along their knowledge to their students with concrete steps on how to take action in big and small ways,” Guarriello says.

Some of those “small ways,” she says, can include “having students help run a concert, go through the process, and then reflect on it.”

Ideally, Guarriello, who was recognized as a 2025 Yamaha “40 Under 40” music educator, says, students should be able to see what they learned from the experience. “It’s not just, ‘I’m helping my teacher,’” she explains. “Instead, students can ask themselves, ‘How did I contribute to the music-making of my community?’”

If students can understand how these behind-the-scenes actions helped to facilitate music, they will be more likely to see this side of music as a potential career path.

Guarriello recommends that teachers reach out to local venues for partnerships. “See if they would be willing to work with you on a project, a unit or some service learning, so students can get a real-life look behind how the music industry work,” she says. “We wouldn’t hesitate to take our orchestra class to a symphony concert, so why can’t we do the same thing for other career paths?”

Challenge the Status Quo

While Guarriello sees obvious benefits in expansive music education, she also acknowledges that change doesn’t come easily. Getting educators on board with expansive music education can be challenging, especially when most people still view music education as a traditional program for winds, strings and choir.

“One of the challenges that music education faces is that we’ve been so established in this performance-centric mode of teaching and learning for so long,” she says. “There are people who firmly believe that’s what music education is, and that’s all it should be.”

However, new music teachers are starting every year, meaning that music education will continue to evolve. “I’m hopeful that as new generations of music educators come through the system, they will maintain an open mind,” Guarriello says. “They might be open to modern music or music production or music administration. They’ll do things that welcome their students into their classroom.”

One of the biggest short-term benefits of expansive music education is the large number of students it has the potential to reach. By expanding the definition of musicianship, teachers can inspire a wider variety of students to give music a try.