Tagged Under:

Case Study: Use Intellectual Discomfort to Expand Music Offerings

At a Wisconsin high school, the music instructor grows the quality of his music program by embracing what he doesn’t know.

Music teachers are unique individuals, but they often share a few common traits.

If you asked them why they chose to teach music, you’ll often hear that they had an incredible experience growing up in their school music programs. Many will point to a former teacher, an experience or a collection of experiences that guided them in their career choice.

A Preference for Teaching What You Know

All music educators want to give their students musical experiences that are just as good as, if not better, than the one they received. This is where an important split forms. Some teachers’ experiences were wrapped around their concert band, string orchestra or concert choir. For others, it was their jazz ensembles. And still others point to their experiences in show choir, pep band, marching band, pops string, etc.

Often, teachers are intrinsically driven to make the favored ensemble from their past the highest quality possible because they have such a clear picture of what they want, they know what success looks like, and they have a strong connection to that particular ensemble.

Often, teachers are intrinsically driven to make the favored ensemble from their past the highest quality possible because they have such a clear picture of what they want, they know what success looks like, and they have a strong connection to that particular ensemble.

In my case, I had fond memories of my concert band and marching band experiences. When I started in my current position at Platteville High School in Wisconsin, I hit the ground running and made changes to those portions of the music program. It was easy for me to identify topics that needed to be taught with a fresh perspective, and, more often than not, I knew what I wanted and how to do it. After a short time, my concert and marching programs looked uniquely different than they did prior to my arrival. Members of the community were coming to me and commenting on how they noticed and appreciated these changes, and I felt good about the direction we were headed.

I assume other music educators have probably had a similar experience in their own programs.

From Cruising Attitude to Discomfort

I quickly reached a spot, which I refer to as “cruising altitude,” with my program. However, I quickly became dissatisfied with the idea of maintaining. I had never faced this before. I suddenly realized that I didn’t want to have a great program, I wanted to build a great program.

This brought me some alarming insight: I wanted to improve the quality of my program but I didn’t know how. I brought the program up to my minimum expectations, but I had exhausted my knowledge and experience. I was faced with the reality that although I had a desire to continue growing, improving and providing opportunities for my students, I had run out topics that I felt comfortable teaching.

I had reached the end of the sidewalk, and I was faced with a decision. Do I settle for what I had already achieved or do I enter the unknown? If I continued forward, I would be forced to teach topics as I learned them in real time. Said another way, I would be required to live in intellectual discomfort.

Embrace Your Shortcomings

The idea of living in intellectual discomfort isn’t well-loved. Teaching topics that you are intellectually uncomfortable with is horrifying! Upon the realization that I would be embarking on a journey into the unknown I was, well, uncomfortable.

My shortcomings fell into three categories:

-

- I was stretching myself past my deepest understanding,

- I hadn’t received any formal training,

- Or worst of all, I hadn’t received training AND I had zero hands-on experience.

I knew that I would run into scenarios where I wouldn’t have the answer on hand or where a student would know more about a topic than I did.

First, I lacked a depth of knowledge regarding jazz. Second, I wanted to enrich the curriculum for my marching percussion and color guard sections. While I had some experience with these topics, I was woefully unprepared to teach these groups myself. Finally, I wanted to delve into the world of digital music production — something I knew essentially nothing about and had no experience with whatsoever.

Diving into Jazz

I waded into these topics by swallowing my pride and seeking information from people with more experience and knowledge than me.

I attended workshops on how to listen to and digest jazz music, and then I spent multiple hours each day listening to different jazz artists. I sought out jazz clinicians and paid them to come to my school and work with my jazz band, and while they worked with my group, I vigorously took notes in the background much like a practicum student — in full view of my students. I subbed in rehearsals with local jazz bands whose skills drastically outpaced my own to see the real application of the skills that I was learning.

Slowly, my eyes started to open to how vast my lack of understanding actually was. I graduated from not knowing what I didn’t know to knowing what I didn’t know — a huge step!

Specialized Staff for Drumline and Color Guard

As the marching season approached, I began to look around the country at what other successful programs were doing. I realized that although the schools around me were doing good things with their marching bands, this focus narrowed my vision to look at models exclusively based on proximity.

I noticed that the strongest programs had specialized instructors for color guard and drumline. The best programs did not have a single instructor doing everything because those instructors had come to the conclusion that they couldn’t be experts in every area.

I decided to follow suit and appealed to my administration for support to give our students a richer marching band experience. When I laid out my plan, the administrators were open to the ideas and supported my recommendation to bring in additional instructors. This was largely thanks to my earnest effort to offer more to students rather than easing the burden on myself.

Digital Music Outreach

The most formidable challenge on my list, digital music production, started with the consideration that modern music education needed to pivot to match what modern musicians were doing. Having zero knowledge on the matter, I drew a terrible sketch of a floor plan of what I thought a recording studio looked like. I pitched the idea and the drawing to my principal, who was interested but skeptical because no school in our area offered anything remotely similar. He wisely saw that I had heart but not much more.

Hopeful, I did what anyone would do. I Googled every term I could think of and quickly realized that I couldn’t learn everything on my own. My colleague and I began to reach out to recording studios for help in creating this new course on digital music production. Not only were these artists willing to help, they explained everything to us from construction of their physical spaces to recommending types of hardware and software.

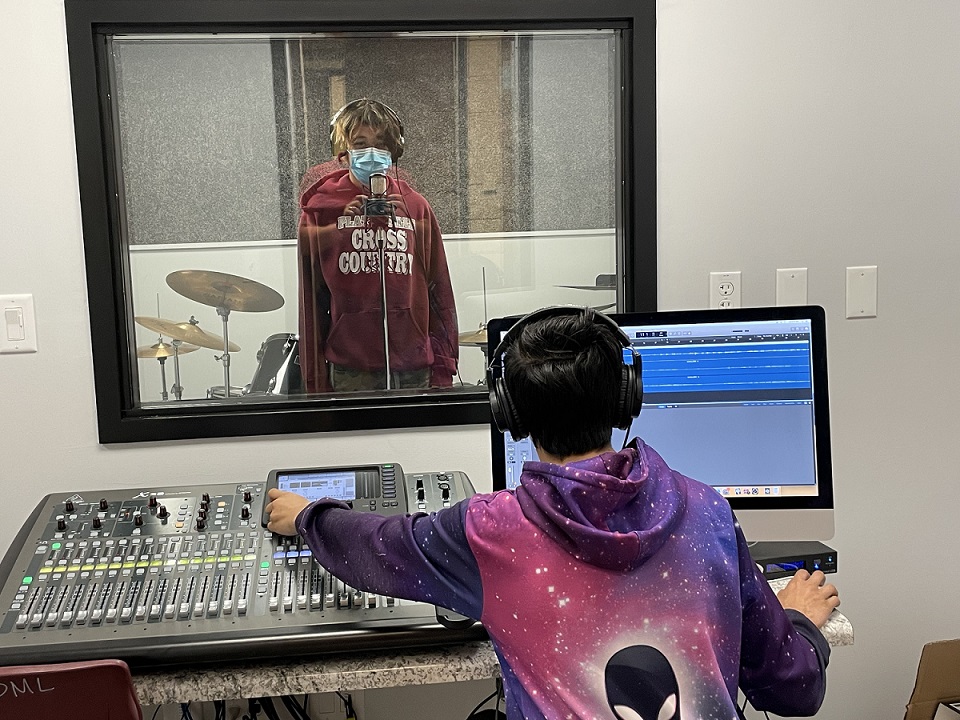

About this time, I began my master’s degree at the University of Illinois and I took a course on digital music production and modernizing music curriculum. This further opened my eyes to the possibilities of a music production course at our school. By this time, we were able to secure several grants to cover the cost of converting a storage room into a recording studio. Every step of the way, we consulted with musicians who knew far more than we did.

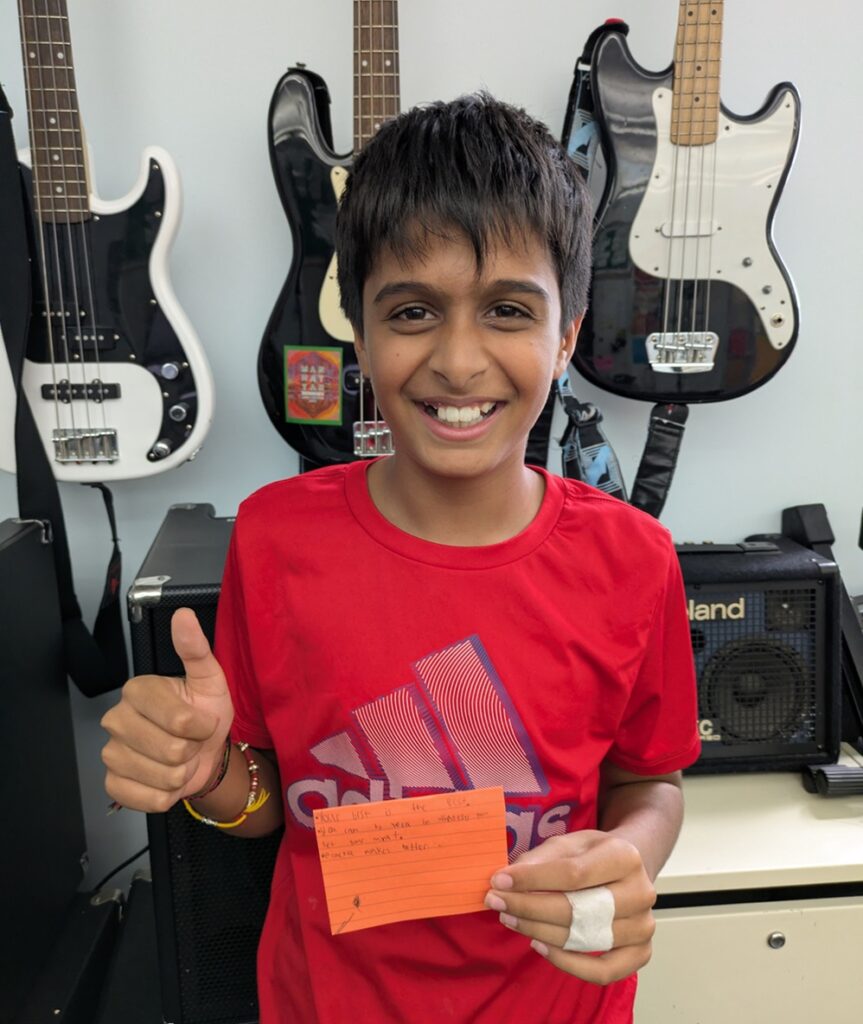

In the fall of 2019, after two years of learning, consulting and writing grants, we had a recording studio in our school! I remember feeling confident that I knew what I didn’t know on the first day of my Digital Audio Production class. Little did I know that I was peering into a doorway of doorways!

In the fall of 2019, after two years of learning, consulting and writing grants, we had a recording studio in our school! I remember feeling confident that I knew what I didn’t know on the first day of my Digital Audio Production class. Little did I know that I was peering into a doorway of doorways!

This class has probably generated more humbling intellectual moments for me than the rest of my cumulative teaching experience. In my effort to build the plane while it was flying, I was forced to see that students had to be stakeholders in the design of the course. Not only that, I had to accept that students could meaningfully contribute toward teaching about new tools. Although it was uncomfortable, I welcomed when a student knew something I didn’t and wanted to share it with the class in a positive way.

In all these instances, the story was the same: I saw my shortcomings, accepted them, made them known to myself and my students, and used every available resource to move forward. There were uncomfortable moments along the way, and more than once, I worried that my boss would wander into the room and think that I was an ineffective educator. What I didn’t consider was that these intellectual risks that I took were signs of a strong teacher, not a weak one.

The Results So Far of My Intellectual Discomfort Experience

Four years of living in intellectual discomfort has radically changed my perspective as a teacher. My program grew in vast ways, but not in the ways that I expected.

For instance, our marching band went from a three-set to a 60-set show and started participating in the Wisconsin School Music Association’s State Marching Championship. Our jazz band split into two ensembles and won recognition at the University of Wisconsin Platteville Jazz Festival, a local competition, for the first time in decades. Two of our students were selected for the state honors jazz band — a first in school history. The pep band has exploded in popularity with the addition of a rock combo, and we have built strong relationships with the sports boosters and families of student athletes. Our concert program is tackling projects that extend far beyond the boundaries of the band room.

For instance, our marching band went from a three-set to a 60-set show and started participating in the Wisconsin School Music Association’s State Marching Championship. Our jazz band split into two ensembles and won recognition at the University of Wisconsin Platteville Jazz Festival, a local competition, for the first time in decades. Two of our students were selected for the state honors jazz band — a first in school history. The pep band has exploded in popularity with the addition of a rock combo, and we have built strong relationships with the sports boosters and families of student athletes. Our concert program is tackling projects that extend far beyond the boundaries of the band room.

We have more students enrolled in music than we have had in quite a long time thanks to the addition of digital music production. We went from 29% our of student population enrolled in music during my first year of teaching to 33% in 2019.

COVID-19 threw us a curve ball — instead of 24 students, our digital music class could only accommodate 10 students during the pandemic. However, the administration has seen the value of the class and has asked us to build a Digital Audio Production 2 course.

Shift Your Focus from Quantity to Quality

When I first started this process, I foolishly convinced myself that, like most music teachers, I should focus on enrollment numbers. As long as the number of students in concert band is high, my program is good. While there’s nothing wrong with increasing enrollment numbers, I understood that what truly matters — and what I truly wanted — was to improve the quality of the offerings. Seen another way, I shifted my focus from quantity to quality during this experience.

This shift resulted in several instances where I was incredibly uncomfortable teaching a particular topic. I’m not ashamed to admit that students have taught me things that I have now incorporated into my regular teaching.

I am also aware that I have a LONG way to go on almost every topic I’ve covered here. So, I’m excited at the prospect of putting myself in more uncomfortable intellectual situations!

Showing my students that it’s okay to be wrong and demonstrating what it looks like to be a lifelong learner are powerful teaching tools. Beyond that, I have noticed that my students are far more willing to open themselves to making mistakes as a way to improve. I firmly believe that this has led to a higher level of retention in my program.

If I were to summarize my entire experience with intellectual discomfort, this quote from Columbia University Professor Randall Everett Allsup (in “Popular Music and Classical Musicians: Strategies and Perspectives”) is the most applicable:

“I realize that discussions about music that include more than its structural components can make a music teacher feel suddenly unsafe and unmoored. But the lack of safety is not the same as danger. Predictability, in music and in teaching, is rarely a place of deep insight.”

My advice for music educators: Embrace your shortcomings and the challenges before you. It’s okay that you’re not the expert in the room all the time. Cruising altitude is comfortable, but intellectual discomfort is much more exciting and meaningful for you and your students.