Altered Tunings, Part 1

A whole universe of possibilities open up when you turn a few pegs.

It happens to every guitar player at some point or other: You get bored with what you’re doing. You feel unchallenged and unhappy. You don’t like the way your instrument sounds anymore. You can’t come up with any new ideas, or maybe you can but they don’t excite you. In short, you’re stuck in a rut.

Luckily, there’s an easy way to fix this problem, and no, it doesn’t involve buying new gear. All you have to do is change the way your guitar is tuned.

Take a guitar out of standard tuning and you instantly change both your instrument’s harmonic resonance and your own way of thinking. When open strings ring out pitches other than E-A-D-G-B-E and notes don’t fall where you expect them to, the music you make stops being familiar. You don’t always know what you’re playing, and that’s a good thing for your creativity.

In practical terms, the benefits of altered tunings are myriad. By expanding or shrinking the intervals between strings, you give yourself the ability to come up with chord shapes and single-note lines that would be difficult or impossible to execute in standard tuning. If you choose to tune to a chord, you make it easy to move chords up and down the neck with a single-finger barre. Altered tunings also allow you to further exploit the ring of open strings at unexpected times, and to add more depth to your playing with drones and pedals.

With this in mind, I’ve selected a dozen altered tunings that you may find particularly useful — six here in Part 1 of this article and another six in Part 2, with brief examples of each one in action. They’re arranged in order of how many strings you have to take out of standard tuning, starting with one and working up to a full six. All tunings are listed from the guitar’s lowest string (6) to its highest (1); the tablature in the music examples indicates where notes should fall on the fretboard in the given tuning.

Two quick things before we get started:

1) One practice we won’t discuss here is wholesale detuning of the instrument, i.e. tuning all six strings down a half-step, whole step, or more. This is a common tactic — in rock music alone, you can find plenty of examples, from Jimi Hendrix to Queens of the Stone Age — but although it changes the sound of the guitar, it doesn’t really change the way a player approaches the instrument, and that kind of creative transformation is what we’re looking for.

2) As you play through the examples, try to let notes ring beyond the duration notated whenever possible. Altered tunings bring out different frequencies in a guitar, and if you cut your notes off too soon, you won’t get to fully enjoy those new vibrations.

Retuning One String

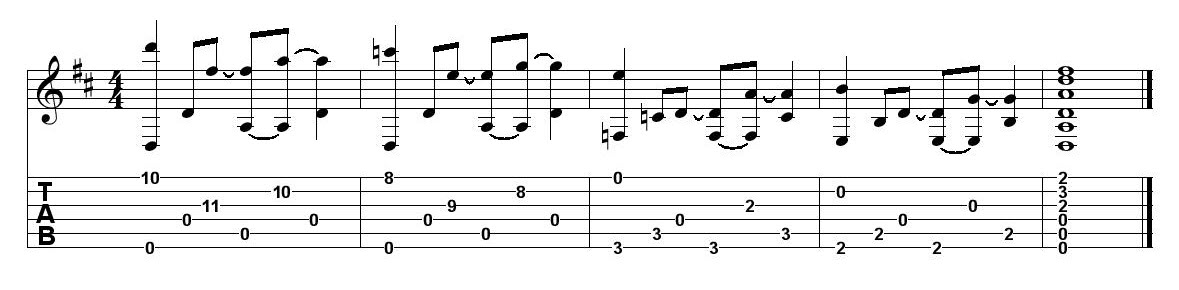

D-A-D-G-B-E (Drop D)

This is probably the most familiar altered tuning, in part because it’s so easy: Just detune your bottom string a whole step. It’s been used in countless songs over the years; one of the best known, the Beatles’ “Dear Prudence,” is the springboard for this example, which demonstrates two handy features of this tuning. In the first two bars, the open strings on the bottom half of the guitar generate a low drone (a pedal) that stays the same while the chords on top change. In the second two bars, you can see how the tuning simplifies the formation of root-and-fifth power chords, which now lie horizontally across a single fret.

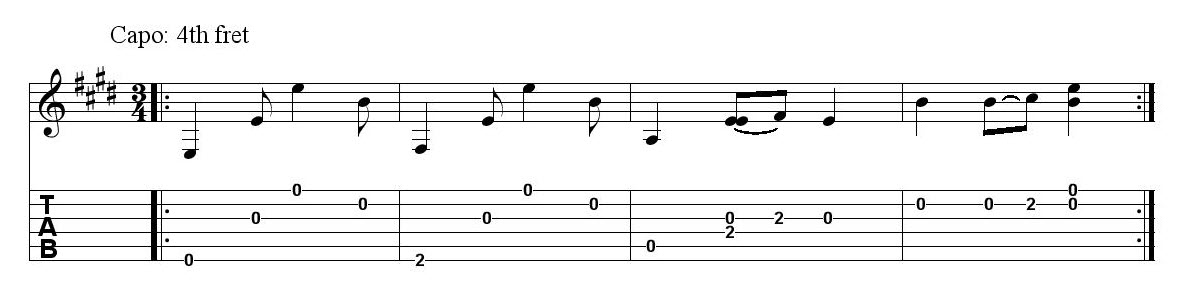

E-A-D-E-B-E (E modal)

Take your 3rd string down a minor third from standard, and you’ve got this wonderfully drony tuning. Playing the open strings by themselves, you can’t tell whether you’re in a major or minor key (that’s the simple explanation for why it’s called “modal”), and the tuning makes a great virtue out of this ambiguity. Ed Sheeran is probably the most famous current user of E-A-D-E-B-E, and the example below was inspired by his song “Tenerife Sea.”

Check out the unison in bar 3: A fretted note on one string resonates against the same note played open on the next string, creating a chorus effect. Try hammering on and/or pulling off the fretted notes for more of a Celtic-folk feel. To play this just like Sheeran would, attach a capo to the 4th fret; the part remains exactly as written here, but the notes will sound in the key of A-flat instead of E.

Retuning Two Strings

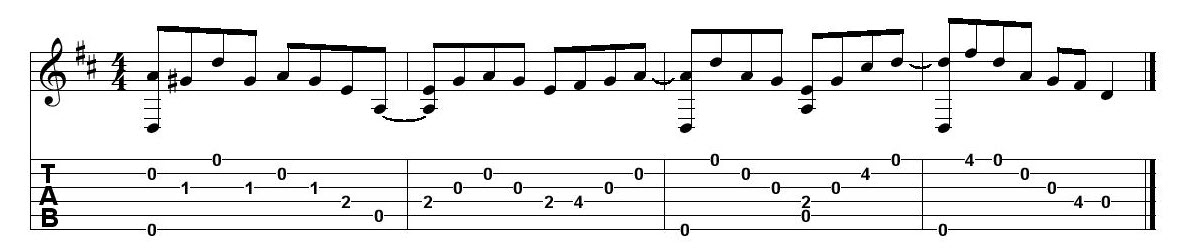

D-A-D-G-B-D (Double drop D)

The logical next step from drop D is to drop the other E string down a whole step as well. This gives you a drone on the bottom and top of the guitar, spanning two octaves. It’s a big, heavy sound, one that Neil Young has exploited to full effect on a number of songs, including “Cinnamon Girl,” which is referenced in the example below. Unisons come into play again, this time in nearly every bar; at one point, a D note is being played in three different octaves on four out of six strings.

Retuning Three Strings

D-A-D-G-A-D (D modal)

Similar to Ed Sheeran’s E-A-D-B-E but deeper due to the greater number of detuned strings (three versus one), this is one of the most popular altered tunings, and you can hear why: It’s got both the heaviness of double drop D and the exciting major/minor ambiguity of E modal.

Some claim that D-A-D-G-A-D tuning (commonly pronounced “Dadgad”) was invented by British folk guitarist Davey Graham in the early 1960s; it’s probably more accurate to say that he popularized it. In any case, many guitarists have used it in the decades since.

A song by one notable Graham disciple, Paul Simon’s “Armistice Day,” was the inspiration for the example below. It emphasizes minor-second intervals between fretted and open strings, several of which (like the opening clash between A and G#) couldn’t be played on a standard-tuned guitar. Be sure to let these close-ringing notes overlap each other at least a little bit — that way, you’ll make the guitar sound more like a harp.

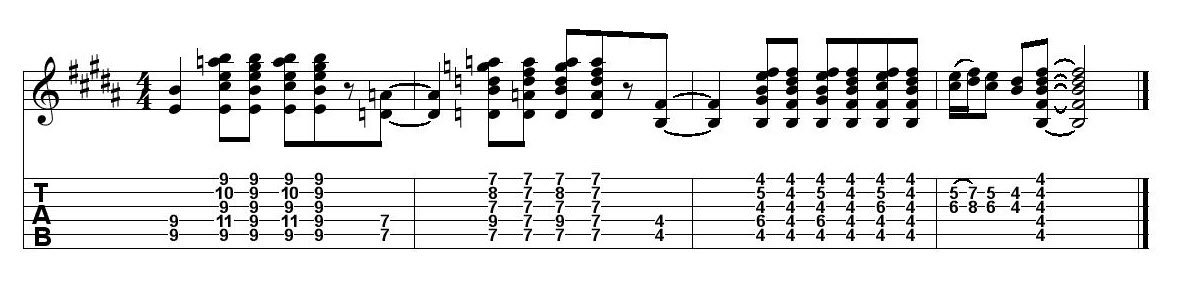

D-G-D-G-B-D (Open G)

The first of our altered tunings to form an unambiguous major chord, this one is especially nice for slide players because it puts all the key notes of a chord on the same fret. But you don’t need to wear a metal bar on your finger to get something good out of open G; rhythm players of any stripe will appreciate it.

Without doubt, Keith Richards is the top user of this tuning, and several songs that he plays with the Rolling Stones — including “Brown Sugar” and “Happy” — inform this example. There’s nothing unusual about these chords in themselves, but the tuning occasionally brings out major-second intervals (between the high A and B in bar 1, for instance) that give them a distinctive jangle. Note that the bottom string is never used here. Richards feels that it gets in the way, and so he often puts only five strings on his guitar when playing in open G. You may not wish to go to such an extreme, but be aware that the low D is optional.

E-B-E-G#-B-E (Open E)

Another open major chord, employed by another legendary user of altered tunings, Joni Mitchell. This example, inspired by her “Big Yellow Taxi,” makes use of the same kinds of major-second intervals and easily movable shapes that we saw in the previous example. But because the three retuned strings go up in pitch rather than down, the guitar sounds brighter and more vibrant.

Tunings like these can make some guitarists antsy, because of the extra pressure they put on the instrument’s neck and the possibility that you could break strings as you tune them up past standard pitch. If you’re troubled by such considerations, try tuning down to D-A-D-F#-A-D (open D) and then putting a capo on the 2nd fret; the result will be basically the same.

In Part 2, we explore guitar tunings that alter the pitch of four, five, and six strings.

The audio examples in this article were performed on a Yamaha FG-TA guitar. For more information on how they were recorded, check out our blog posting “How to Record TransAcoustic Guitar Effects.”

Click here for more information about Yamaha guitars.