Altered Tunings, Part 2

Here are some more alternative guitar tunings to unlock your creativity.

In Part 1 of this two-part series, we looked at some popular alternatives to standard guitar tuning, including such favorites as drop D, double drop D, D-A-D-G-A-D, and a couple of open tunings (which produce the sound of a full chord without your having to put a finger on the fretboard). For each of those tunings, you have to alter the standard pitch of either one, two or three strings on your guitar.

In this article, we move on to tunings that require you to retune four, five and, finally, all six strings. We’ll start with some additional open chords, and then wander further afield into tunings that some might find a bit more odd. Again, all tunings are presented in typical pitch order, from lowest string to highest.

Retune Four Strings

E-A-C#-E-A-C# (Open A)

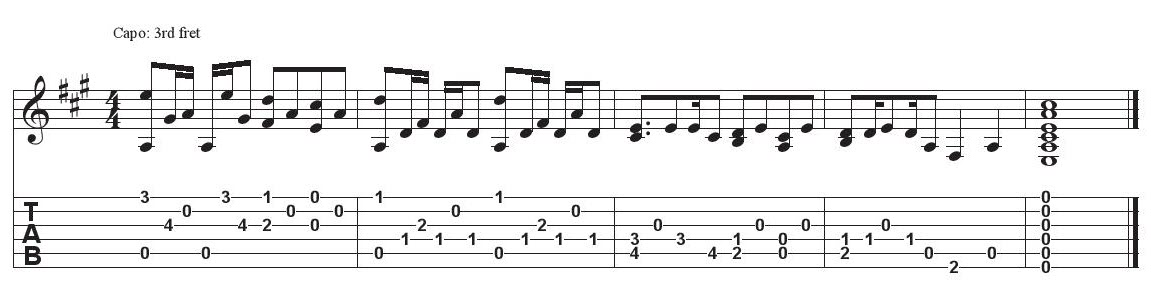

You’ve got to admit this tuning has a cool symmetry: the top three strings mirror the bottom three strings, only an octave higher. Although the bottom two strings stay the same as standard, the detuning of the other four strings makes the whole thing sound surprisingly low, which is probably why most players who use this tuning have a capo handy.

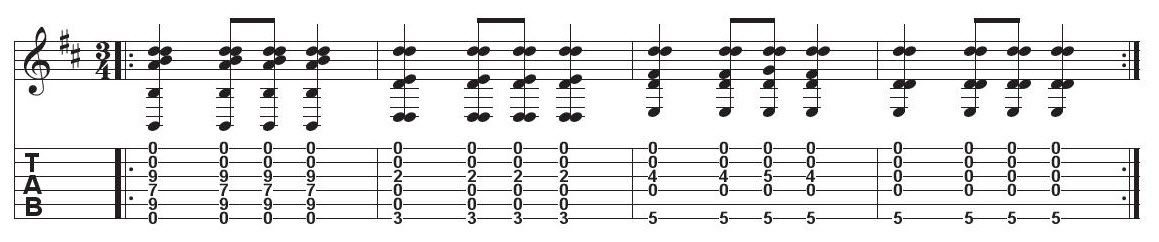

Bob Dylan put a capo on the 3rd fret when he used open A for his song “One Too Many Mornings,” which is referenced in the example below. If you choose to do as he did, note that what you hear will actually be in the key of C rather than A:

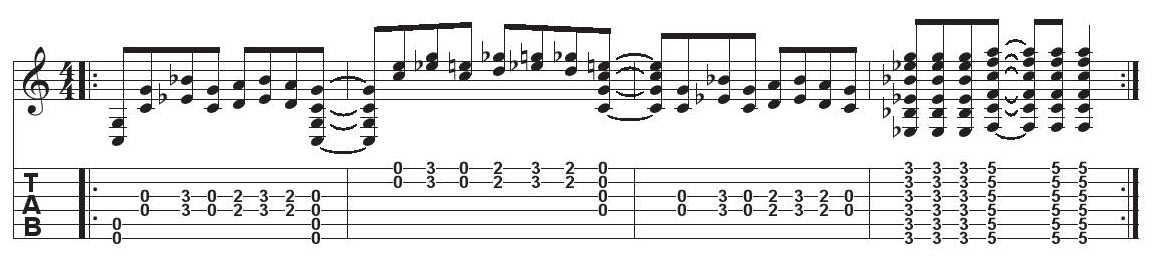

C-G-C-G-C-E (Open C)

What’s the difference between tuning your guitar this way and playing in open A capoed up to the 3rd fret (as in the previous example)? You don’t have the same cross-string symmetry as before, but you do get a high E, which adds brightness to the guitar’s tone, and a low C, which balances out that brightness with extra heft. This is a particularly nice tuning for slide playing, and it also responds well when you throw in a little dissonance, as Jimmy Page learned when he used it on Led Zeppelin’s “Friends,” the inspiration for this example:

Retune Five Strings

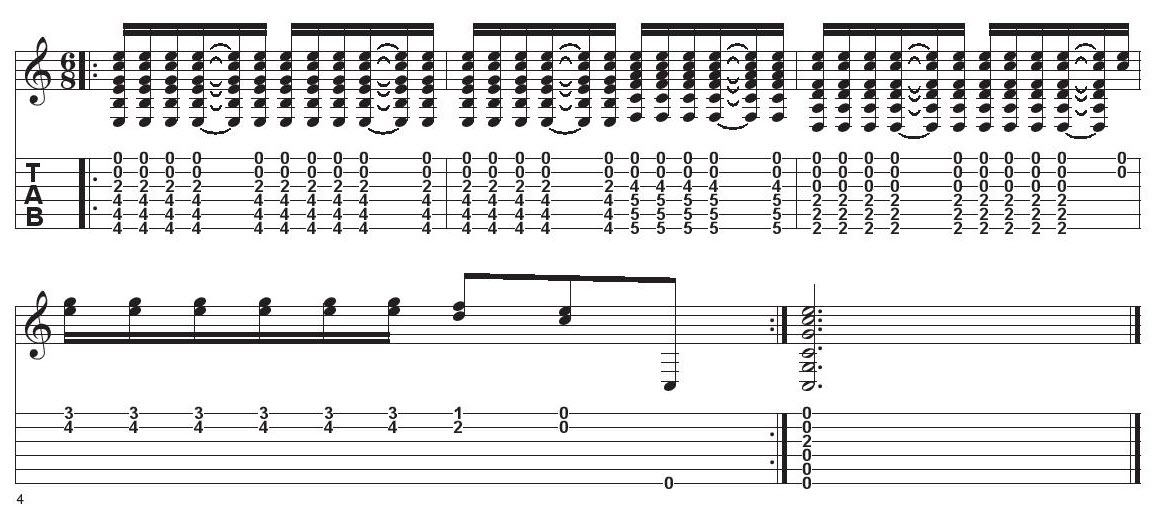

C-G-C-F-C-E (Csus4)

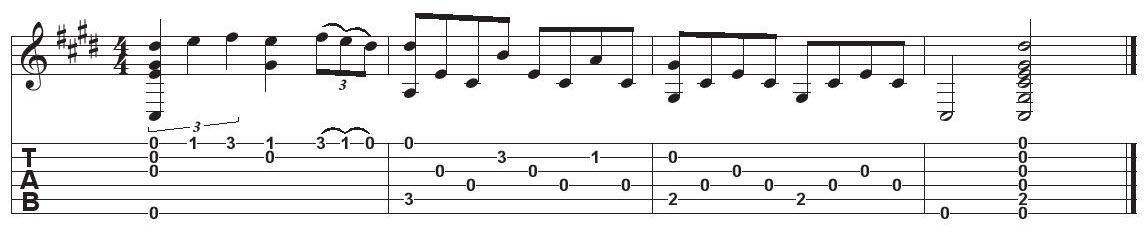

Just one note has changed here from the previous tuning, but that whole-step descent for the 3rd string is a real mood shift. The presence of an interval of a fourth (represented by the F) gives this tuning a modal flavor similar to D-A-D-G-A-D, but you don’t have the same kind of major-second interval between two adjacent strings. And that ringing major third (C to E) on top makes the sense of key less ambiguous than it is when you tune to D-A-D-G-A-D. It’s not sad-sounding exactly, but it is reflective. This is one of many unusual tunings that were employed by the late great British troubadour Nick Drake; this example was inspired by his “Place to Be”:

B-F#-B-E-A-E (B modal)

Anyone who uses altered guitar tunings has to reckon eventually with the master: Joni Mitchell, who employed about 60 different ones over her career, many of them unique to her. In Part 1, we checked out her use of open E, but that’s pretty normal stuff compared to this low, ominous tuning, which distinguishes her song “The Magdalene Laundries.” There’s no clear third to be found in this example, making everything sound hauntingly unresolved:

B-D-D octave-D unison-D octave-D unison (“Iris”)

The most bizarre tuning of our dozen was discovered by the Goo Goo Dolls’ Johnny Rzeznik, another guitarist who’s fond of messing around with his tuning pegs. He’s playing it on the band’s massive late-’90s hit “Iris,” and that sound of a single note ringing in three octaves with two unisons is pretty distinctive.

To make it completely clear what you do here: The 6th string goes down a minor third from standard, the 5th string goes down a full fifth, the 4th string stays the same as standard, the 3rd string goes down a fourth, the 2nd string goes up a minor third, and the 1st string goes down a whole step. Tuning that 2nd string all the way up to D can be a little hair-raising; if you want to use this tuning regularly, you might want to consider setting up a guitar especially to handle it:

Retune All Six Strings

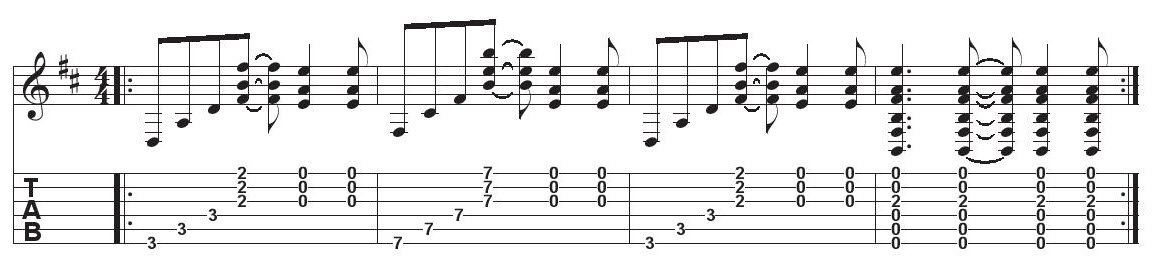

C#-F#-C#-E-G#-D# (C#m9/11)

This is one of my own discoveries; other players may have used it at some point, but I am unaware of who they might be. It’s the only tuning out of our 12 examples that you can immediately tell is in a minor key, but it’s not quite an open chord — at least not one you’d play all that often. You need to put a finger or two down on a fret before it really starts yielding melodic returns, but when you do, it’s memorable, as demonstrated here:

Of course, these short examples give you nothing more than a brief introduction to what altered tunings can do. To really understand what these examples can do, you’ll have to dig deeper. Ask yourself the following questions: How do the chord shapes you’re used to playing in standard tuning adapt (or not) to different tunings? What other shapes can you try?

Altered tunings can be inspirational and a wonderful boost to creativity. They give you a chance to break out of old routines, throw away the rule book, and just have fun. So next time you put new strings on your guitar, don’t tune them up to standard immediately — stop at a random point on the way and give a couple of strums. Maybe you’ll hear something that’s interesting but not quite right to your ear. Turn the pegs until it does sound right, and then see what that sound brings out in you. With a little time and imagination you’re bound to come up with a number of exciting ideas of your own.

The audio examples in this article were performed on a Yamaha FG-TA guitar. For more information on how they were recorded, check out our blog posting “How to Record TransAcoustic Guitar Effects.”

Click here for more information about Yamaha guitars.