Louder Isn’t Always Better

Yamaha Adaptive Low Volume compensates for the quirks of human hearing.

Did you ever notice how music sounds better when you turn up the volume? The louder it is, the more bass and treble you hear. But when you turn it down, the midrange becomes more prominent as those low and high frequencies recede.

That phenomenon is a function of how the human ear works. It’s a bit problematic when you want to listen to music quietly, because what you hear tends to sound thinner and less exciting. Fortunately, audio gear manufacturers have come up with various ways to compensate. Yamaha Adaptive Low Volume, incorporated in the company’s new SR-C30A compact sound bar, is the most recent — and most advanced — of such loudness-compensation technologies.

Before getting into how Adaptive Low Volume works, though, a little background is helpful.

The Fletcher-Munson Discovery

Back in the 1930s, a pair of scientists named Harvey Fletcher and Wilden A. Munson were the first to discover that humans perceive frequencies differently at various levels. Their experiments on a group of headphone-wearing test subjects led to the creation of what are known as Fletcher-Munson curves.

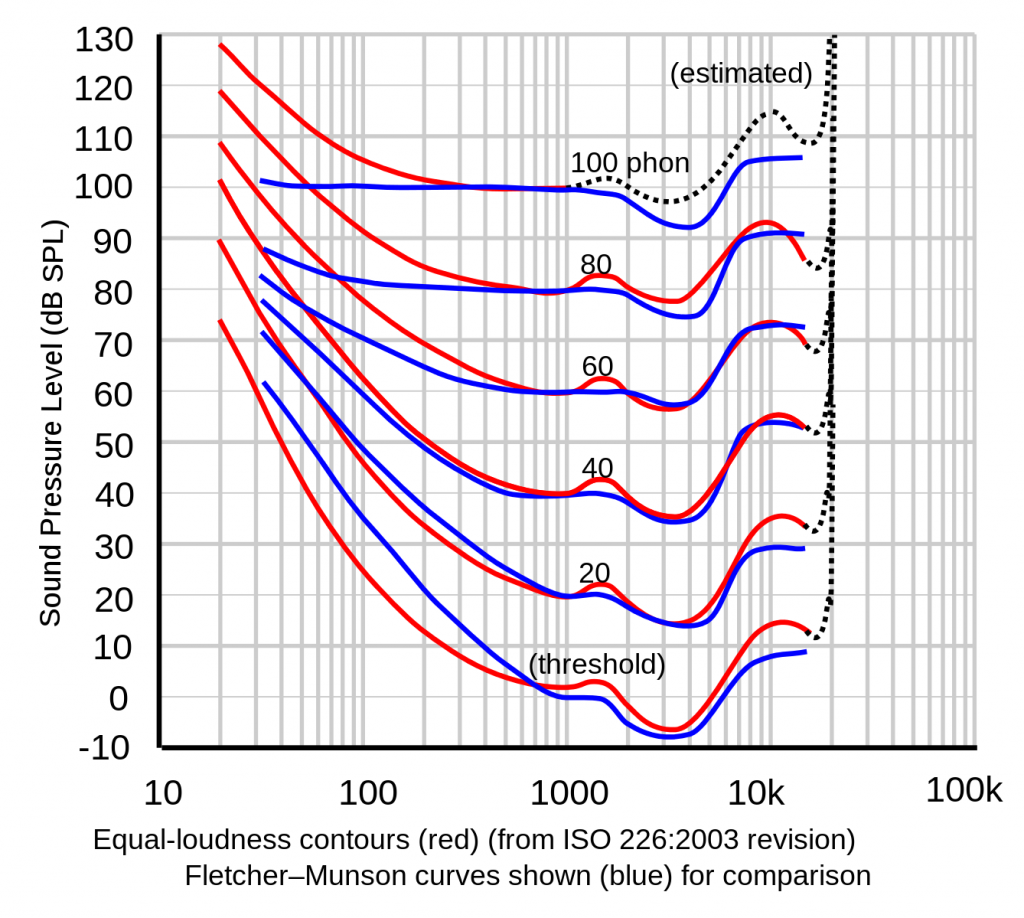

Expressed in graph form, these curves map out how we hear frequencies at different volume levels. Fletcher and Munson’s findings, incorporated with subsequent research, are now considered a subset of the Equal Loudness Contours, published by the International Standards Organization (ISO). Although the curves have been updated, Fletcher and Munson’s original concept has held up over time.

The Equal Loudness Contours are shown below. The vertical axis represents volume (specifically, the Sound Pressure Level, in decibels) and the horizontal axis represents frequency (in Hertz). The red and blue lines show how loud each frequency needs to be in order to be heard equally, as compared to other frequencies. (The red lines incorporate modern research, while the blue lines show Fletcher and Munson’s original findings.) The lines are curved because we hear more high and low frequencies at different volumes; they’d be flat if we heard them at equal volumes.

Compare the lowest and highest of the red curves. This shows you that the louder the volume, the less variation there is. In other words, we hear frequencies more evenly at louder levels than at quieter ones.

Manipulating the Mids

Over the years, a control called “Loudness” has been audio gear manufacturers’ primary weapon against those “lost” low and high frequencies. Typically found on stereo receivers, this control boosts low and high frequencies so music sounds full and rich even when the volume is turned down. In some products, it’s a simple on-off switch; in others (like the Yamaha R-N1000A), various degrees of Loudness can be engaged. Sometimes the degree of boost is automatically adjusted, depending on the position of the main volume control: the higher the volume, the less the boost, until the loudness circuit is removed from the signal path altogether.

The concept has been around since before the digital era. However, it’s now usually implemented with DSP (digital signal processing), which can do a more precise job than older analog circuitry.

In the Quiet Night

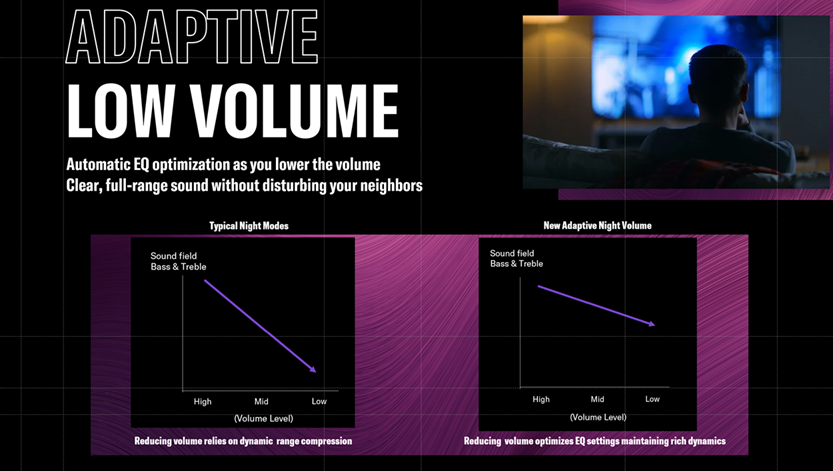

In recent years, some manufacturers have equipped their wireless speaker systems with a variation on loudness compensation that uses compression (the reduction of levels that exceed a certain threshold) to decrease midrange frequencies at low volumes. Typically referred to as a “night setting,” it’s designed to allow you to listen to music or watch movies with the volume turned down low so as not to bother others in your home.

The problem with such a system is that the compression reduces the dynamic range (the difference between the quietest and loudest signals) of the audio as a whole. This tends to homogenize the sound, making it less pleasing to the listener.

Changing with the Volume

And that brings us to Yamaha Adaptive Low Volume. While Yamaha has integrated loudness compensation systems of various types into its consumer audio products for years, Adaptive Low Volume technology, available in products like the aforementioned SR-C30A sound bar (which includes a wireless subwoofer), represents a new level of quality and accuracy.

The Adaptive Low Volume system is built into the unit’s volume control circuitry. You don’t need to turn it on; it’s always active. It keeps your music sounding full by employing sophisticated equalization, not just of the low and high end, but the midrange frequencies too. It’s called “Adaptive” because it’s constantly monitoring the audio, applying just the right amount of boost and cut to keep a consistent sound regardless of volume. What’s more, because it uses EQ instead of compression, it doesn’t affect dynamic range, so what you hear remains true, even when you’re enjoying music late at night and don’t want to disturb others.

Über-cool … and a great example of how technology can be used to maintain quality sound at all listening levels!