Bringing the Joy of Music to the Hard of Hearing

Meet the inventor of machines that allow music to be seen, not just heard.

Musician and inventor Myles de Bastion has been deaf since he was four years old, and he has a lot to teach the world.

The president of CymaSpace, a Portland, Oregon-based nonprofit technology company that works to bring art and culture to the deaf community via innovative practices, de Bastion is both a creative individual and one seemingly in constant professorial mode. While society often refers to those without traditional hearing as “hearing-impaired,” de Bastion says many in the community actually prefer “hard of hearing,” noting that all people, even those with normal hearing capabilities, are on a spectrum.

Further, through his work, de Bastion says he’s learned to consider himself not afflicted with “hearing loss.” Rather, he says, he has “deaf gain,” which has made him more resourceful in his life. Evidence of this ingenuity lies in the fact that de Bastion has helped to design several unique technologies that actually show sound to those who cannot hear it — in essence, creating a form of visual music.

An Inventor Begins His Journey

de Bastion’s education and creative spark began when he was a child, playing the piano on his grandfather’s lap.

“It was one of my earliest memories,” he says. “I would marvel at the repeating pattern of the black and white keys. When I would copy his movements and strike a key, I wasn’t so much aware of there being a sound, but rather that the keys on the left made more of a vibration under my fingers than those on the right. That sensation was what drew me in.”

As a teenager, de Bastion says he became “obsessed” with music. He started to learn the electric guitar, which, he’d noticed, has a great deal of malleability when it comes to amplification and sound manipulation. He joined a band but found the experience frustrating, not knowing what the lyrics were and never totally knowing if he was playing the right part. “I wished for a system that could show me visually what was happening in the sound waves as I played,” he recalls.

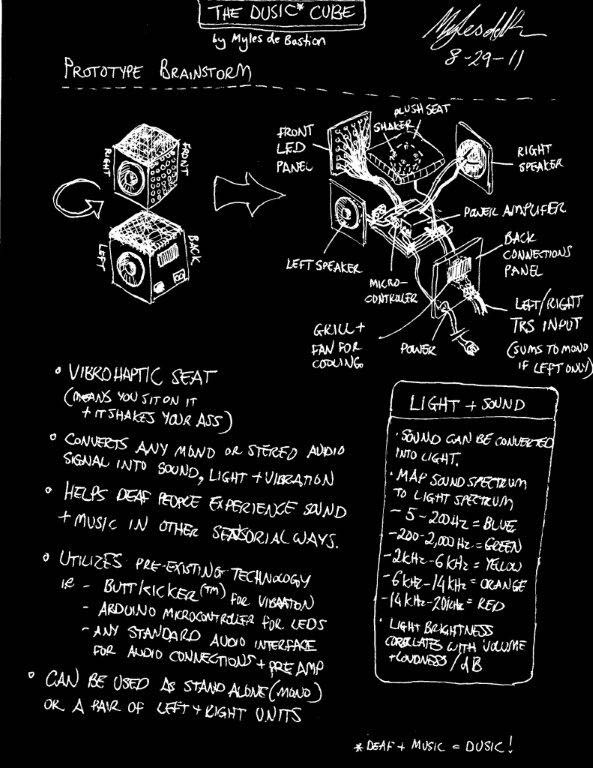

Necessity being the mother of invention, de Bastion started inventing. With the goal of not just displaying the intensity of sound but also the notes being played and the ways different instruments weaved together, he drew up a design for a box he could sit on that would vibrate and light LEDs, with different colors representing different tonal regions.

To turn the idea into reality, he enlisted the help of an electronics-savvy friend and in 2011, the first prototype of the “DUSIC (Deaf Music) Cube” was unveiled. It was later displayed at the Portland Art Museum.

Doubling Down

After the success of his first prototype, de Bastion, who’s also helped to create the first ever deaf arts festival in Portland, was encouraged to continue and expand his work. He began to study more about LEDs and piezo-electronics, later progressing to software coding and even more sophisticated endeavors. Yet de Bastion never saw his innovations as a cash cow. Instead, he gave them away.

“I leaned heavily on open-source hardware and software and free information on the internet,” he says. “As such, I never pursued patenting or claiming ownership over my ideas.”

Today, de Bastion has created several different manifestations of his visual sound system that use varying technologies. These machines are all bound by a scientific approach to interpreting sound as light. For example, the audible sound spectrum mirrors the visible light spectrum so that the lower frequency tones appear as warm, red colors and the higher frequency ones are shown as cooler, blue colors, with the intensity of the sound usually reflected in the brightness of the LEDs.

“This works well for complex multi-spectrum sound sources such as orchestral music or a rock band,” de Bastion says. “Deaf people are very visual, and so it makes sense to tell a story through light, color and movement, especially when it is in sync with sound and vibration.”

To visualize individual instruments with smaller, more restricted ranges of sound, de Bastion relies on repetition of color patterns. For example, when displaying a chromatic scale, the same colors will repeat with each octave. “It is important that the visualization [be] consistently repeatable for it to be functionally useful,” he explains.

Making It Manageable

For de Bastion, who started playing electric guitar at 14 and would practice for six to eight hours per day back then, music is a world in which he wants to live … and he wants others to be able to do so as well. He credits his childhood with teaching him how to stay driven and focused. “When you’re hard of hearing as a young person, you learn how to pay very close attention to other signifiers,” he says. “Persistence is key.”

He also finds it helpful to break up big problems into smaller challenges. “When an event or piece of information is not accessible to me,” he says, “it motivates me to find ways to break down the barriers so that I can have full access. I’ve learned that when I share my experience openly with others, people are more understanding and willing to find ways to communicate or work with me.”

In the end, he views all of this effort as being about connection, art and innovation. Those are the key factors that serve as the impetus behind his personal driving force.

Adapting to Present Realities … and a Vision for the Future

With many venues shut down due to the events of the past year and a half, de Bastion has turned his focus to virtual reality, working to create spaces where people can share in his inventions.

“Trying to perform or engage with an audience through Zoom is very limiting,” he says, “especially since sign language relies on 3D spatial awareness and video compression makes things blurry and seemingly more bland. I have been able to adapt my visual sound concepts into the 3D space. Virtual reality is a good way of doing this because we can immerse ourselves in a rich 360-degree environment that responds to our presence.”

de Bastion can even imagine a value to his work beyond the bounds of this planet. “Music is universal,” he says, “because everything is vibration. If there are other beings out there, I have no doubt they have appreciation for music.”

All photographs courtesy of Myles de Bastion.

For more information, visit myles.debastion.com.