Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

Where does your knowledge base begin?

Sir Isaac Newton (who, as the commercial says, clearly knew a thing or two about seeing a thing or two), once modestly said of himself, “If I have seen further [than other men], it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”

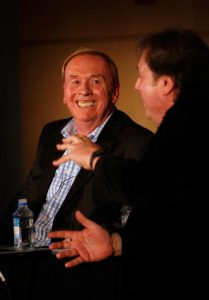

We lost one such giant a couple of months ago: legendary audio engineer Geoff Emerick, who I’ve written about here before — and for me it was personal, as Geoff and I were close friends for nearly two decades. Beyond the numerous innovations he brought to the art of recording (as exemplified in many of the great Beatles records he, along with producer George Martin, helped bring to the world), Geoff was a humble man who devoted much of his last years to reaching out to students. I have many happy memories of wandering around trade shows with him; it seemed we could never move more than 50 feet without being stopped by an aspiring musician or home recordist who wanted to chat or take a selfie, and Geoff was always generous with his time and ready to offer advice and an encouraging word.

He and I often did presentations to audiences that included young men and women who weren’t even born when Beatles records were dominating the airwaves, and I could see a little skepticism in some of their eyes as we were being introduced. Both Geoff and I understood how they might feel that the recording techniques we would be discussing — mostly developed in the 1960s — were not especially relevant to them, or the modern genres of music they were interested in. It was at those moments that I would toss out the Isaac Newton quote, and it was with some degree of satisfaction that I would see an “Oh, now I get it” look on many of those young faces.

The point is this: Nobody begins their career in a vacuum. Geoff’s knowledge base began with the underlying work done by Thomas Edison and Emil Berliner (inventors of, respectively, audio recording and the phonograph record), Jack Mullin (developer of the tape recorder), Alan Blumlein and Georg Neumann (pioneers in microphone design), Les Paul and Tom Dowd (who created and defined the art of multitrack recording), as well as his own personal mentor at Abbey Road Studios, Norman Smith, who engineered all the early Beatles records.

Every aspect of music creation and music-making has their giants. Composers build upon the epic works of Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin and Tchaikovsky; songwriters on the tunes of Stephen Foster, Irving Berlin, Lieber/Stoller, Holland-Dozier-Holland and Lennon/McCartney. Classical pianists develop their performance skills by closely studying Rachmaninov, Gould, Horowitz and Rubinstein. Saxophonists learning to improvise take inspiration from Charlie Parker and Coltrane; trumpeters from Louis Armstrong, Dizzie Gillespie and Miles; bassists from Mingus, James Jamerson and Jaco. Jazz guitarists search for new fingerings and chord inversions based upon those of Charlie Christian, Wes Montgomery, Django Reinhart and Barney Kessel, just as classical players aim to further refine the technique of Segovia, Julian Bream and John Williams. Even modern rock guitarists refer back to past masters like Chet Atkins, Scotty Moore, Chuck Berry, Jimi Hendrix and Duane Allman.

So as we start a new year, this might be a good time to reflect on some of the musical giants upon whose shoulders you stand. Who are they, and what have you learned from them? You might be surprised at how much relevance the old can have to the new.

Photo by Mark Von Holden/WireImage.