Words and Music

It’s all in the phrasing.

Have you ever read something that “clicked” and stayed with you a long, long time? Ever hear a piece of music that did the same?

You may be surprised to learn that the reasons you fall in love with a song (or symphony) are very similar to those that make you connect with a short story (or novel): Something in it “speaks” to you, making you feel as though the songwriter/composer/author were addressing you, and you alone.

It might seem that this comes down to emotional impact, and to a large degree, that’s true. How you are feeling at the time — the trials and tribulations of life that you’re going through when you’re first exposed to the work — has a huge bearing on how something resonates. I know that, for me, the songs I strongly related to as an adolescent (as well as some of the books I read at the time) are the ones that have stayed with me throughout my entire life, and that seems to be true for most people I know. There have been numerous scientific studies that prove the point empirically, but really this is just one of those common sense things: The angst we all go through in our teenage years and early 20s — when we are trying to figure out who we are and how we fit into the world around us — not only creates lasting memories but shapes (and to a large degree determines) lifelong affinities.

In terms of music, it’s true that, in some cases, the words being sung are what “speak” to you, but I think that relatively few people gravitate to a song for that reason alone. After all, nobody goes around humming lyrics! Besides, there are plenty of powerful and enduring musical works that are purely instrumental.

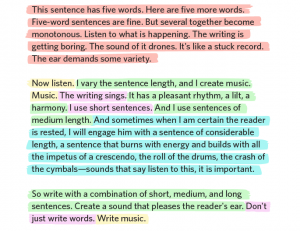

I would argue that, most of the time, what makes us relate to a song, sonata or symphony is the way the music itself is constructed, in the same way that what appeals about a short story or novel is the way the sentences are constructed (or, in the case of poetry, the way the words are strung together). I was reminded of this recently when I came across the following quote from the late Gary Provost, a noted author and writing instructor:

This advice was, of course, aimed at writers, but it could just as easily be applied to songwriters and composers, as well as to musicians of every stripe.

Put in musical terms, what Provost is describing is phrasing, a word that Wikipedia defines as:

The way a musician shapes a sequence of notes in a passage of music to express an emotion or impression. A musician accomplishes this by interpreting the music … by altering tone, tempo, dynamics, articulation, inflection and other characteristics. Phrasing can emphasize a concept in the music or a message in the lyrics, or it can digress from the composer’s intention.

This is pretty much on the money, though I personally would amend the first and second sentences to include songwriters and composers, who have an equal capacity to shape music to convey emotion. John Lennon, who seemed to have an inborn instinct for phrasing, is perhaps the perfect example. Listen closely to the way he shifts the lead vocal patterns in his song “I Am The Walrus,” creating interest in what is essentially just a fairly boring five-note melody. Or check out “Strawberry Fields Forever,” with its abrupt meter change from 4/4 to 3/4 in the chorus that adds a sense of urgency and contrasts powerfully with the laconic and rhythmically straightforward verses.

Frank Sinatra was another master of phrasing. The way he stretches some notes and clips others, starting some on the beat, others just before or after it in his rendition of the song “New York, New York” is the secret sauce that makes the recording iconic. Or, for another great example of the way a vocalist can bring new life to a song, take a listen to Bobby Darin’s still astonishingly hip 1959 recording of the song “Mack the Knife,” which was composed by Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht for light opera way back in 1928. Of course, there are a slew of modern vocalists, from Sam Smith to Ed Sheeran, Celine Dion to Adele, who pour a ton of emotion into just about every note they sing, giving each song their personal stamp.

Phrasing is also what distinguishes one instrumentalist from another. Take any classical or jazz composition and listen to how it’s played by any four skilled soloists. You’ll likely hear four quite different interpretations of the same piece — sometimes subtle, sometimes radical, but with each adding new intent to the composer’s original conception, as memorialized in dots on a line.

It’s all deeply personal and subjective, of course, but I think we can derive some universal truths about the importance of phrasing, in both the literary and musical worlds. And so, with a nod to Gary Provost, this is the advice I would offer to writers of words and writers of music alike … and to performers of music as well: Don’t just write words; craft lasting documents that sing to the reader. Don’t just compose (or play) notes; create lasting works that speak to the listener.

These are the guideposts to originality … and the keys to success in your chosen field.