A Bassist’s Guide to Modes, Part 2

More modes, more melodic possibilities.

In Part 1 of this two-part series, we described major, minor and diminished modes. This time, we’ll look at the pentatonic scale and the symmetrical diminished scale, as well as the most commonly used modes of the melodic minor and harmonic minor scales.

Keep in mind that there’s always more than one way to finger a sequence of notes. I’ve chosen the ones I consider easiest to play on a four-string bass with standard tuning, but you have more options if you detune or use a five-string bass. And although we’d usually stick with either sharps or flats as we spell out a mode, we’ve mixed our accidentals to make things easier to understand: It might be more theoretically correct to call a note “G♭” based on where it is in the scale, for example, but we’ll call it F# to keep things simple.

Before we get back to modes, though, let’s explore two scales that are just as common as the minor and major scales: the pentatonic minor and pentatonic major, both of which contain just five notes.

THE MINOR PENTATONIC SCALE

If you’ve listened to the blues, rock or jazz, you’ve heard the minor pentatonic scale. In the key of G, it consists of the notes G, A, B♭, C and D. Here’s a two-octave minor pentatonic scale in G:

And here’s an audio clip that demonstrates what it sounds like:

(Note that each two-octave scale or mode played in these audio clips is accompanied by an organ drone in G and a metronome click at 60 beats per minute.)

Here’s a reggae bass line that takes full advantage of the minor pentatonic flavor:

THE MAJOR PENTATONIC SCALE

The major pentatonic scale in G consists of the notes G, A, B, C and D.

As with the minor pentatonic shape, you’ll come to recognize the major pentatonic box, too. Here’s what it sounds like:

And here’s an old-school funky blues groove that uses the major pentatonic scale:

The next scale is a cool color that’s most at home in jazzy situations.

THE SYMMETRICAL DIMINISHED SCALE

Symmetrical diminished scales are eight-note patterns that alternate between whole steps and half steps. There are two types: the whole-half scale and the half-whole scale. Here’s the whole-half sequence:

This scale starts on the root, goes up a whole step, and then alternates between whole steps and half steps until it reaches the octave. In the key of G, the notes are G, A, B♭, C, D♭, E♭, E, F# and G.

Most songwriters use diminished chords mainly as transitions between diatonic chords, but film composers take full advantage of their unsettled, eerie feeling, as demonstrated below.

The half-whole scale starts on the root, goes up a half step, and then alternates until it reaches the octave. In the key of G, the notes are G, A♭, B♭, B, C#, D, E, F and G.

Diminished scales go well with dominant chords, and many bass players use them for interesting fills.

On this mysterious-sounding interlude, the bassline slides into notes from a half-step above:

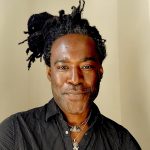

Ready to learn more? Here’s John Patitucci talking about playing diminished scales in a jazz context.

THE HARMONIC MINOR SCALE

Your ears are most likely accustomed to the major, minor, dominant and half-diminished (m7♭5) chords we discussed in the previous column, but the diminished, augmented and minor/major flavors we hear in harmonic and melodic minor modes can take us into new sonic territory.

The minor scale we discussed in Part 1 can be called the natural minor scale. The only difference between the natural minor scale and the harmonic minor scale is the seventh: The natural minor scale has a minor seventh, while the harmonic minor scale has a major seventh. In the key of G, that’s G, A, B♭, C, D, E♭, F# and G.

Here’s what it sounds like:

This mode has been used in countless songs, from the Eurythmics’ “Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)” to No Doubt’s “Don’t Speak.” Here’s a distinctively cinematic interlude grounded by a bass ostinato:

Next, let’s take a look at two of the seven modes of the harmonic minor.

LOCRIAN (natural 6)

The second mode of G harmonic minor is a Locrian scale that begins on A. Think of a Locrian sequence — a diminished scale with a flatted second, flatted third, fourth, flatted fifth, flatted sixth and flatted seventh — and then make the flatted sixth a natural sixth. The A Locrian natural 6 mode consists of the notes A, B♭, C, D, E♭, F#, G and A.

You may also see this scale called a Dorian ♭2 ♭5 or a Locrian #6.

Many classic metal songs (such as Rainbow’s “Gates of Babylon”) make great use of the Locrian natural 6. Here’s an evocative interlude that uses this mode:

PHRYGIAN DOMINANT

The fifth mode of G harmonic minor is a Phrygian mode that begins on D. Start with a Phrygian sequence — a minor scale with a flatted second and a flatted sixth — then raise the third a half step and lower the seventh a half step. The D Phrygian dominant mode consists of the notes D, E♭, F#, G, A, B♭, C and D.

You may also see this scale called a Phrygian natural 3.

If the Phrygian dominant sounds familiar, you might’ve heard it in the traditional Jewish folk song “Hava Nagila” or as part of the main riff of Muse’s “Stockholm Syndrome.” Here’s a jazzy example:

THE MELODIC AND JAZZ MINOR SCALES

Unlike other scales we’ve looked at, the melodic minor scale ascends one way and descends a different way. On the way up, it has a major seventh, like the harmonic minor scale, as well as a sixth instead of a flatted sixth. On the way down, it has the same notes as a natural minor scale. In the key of G, it ascends G, A, B♭, C, D, E, F#, G and descends G, F, E♭, D, C, B♭, A, G. As you can see, most of the notes are the same except the ascending (green) and descending (blue) ones.

Here’s how it sounds in the key of G:

Classical music uses both ascending and descending forms of the melodic minor scale, but in jazz, most musicians use the “jazz minor” scale, which uses the ascending version — 1, 2, ♭3, 4, 5, 6, 7 — both up and down. (You’ll sometimes hear the jazz minor referred to as the melodic minor scale.) Here’s a two-octave G jazz-style melodic minor scale (G, A, B♭, C, D, E, F#):

It can be helpful to think of it as a Dorian shape with a major 7.

Muse used the harmonic minor scale in the pop tune “Plug In Baby,” but it works in jazzier contexts also.

Here’s a fun overview of the modes of melodic minor, but let’s take a look at a couple of the most commonly used flavors.

LYDIAN DOMINANT

The fourth mode of G melodic minor is a Lydian dominant (or Lydian ♭7) that begins on C. Think of a Lydian scale — a major scale with a sharped fourth — and flat the seventh (hence the “dominant” tag). The C Lydian dominant mode consists of the notes C, D, E, F#, G, A, B♭ and C.

The combination of the sharped fourth and the flatted seventh helps give the Lydian ♭7 its particular sound.

Many jazz standards, including “Take the ‘A’ Train” and “The Girl from Ipanema,” use the Lydian dominant tonality. Here’s a jazzy organ groove inspired by the Lydian ♭7 mode:

SUPER LOCRIAN

The seventh mode of G melodic minor is a Locrian scale that begins on F#. Think of a Locrian scale — a diminished with a flatted third, a flatted fifth and a flatted seventh — and then add a flatted second, flatted fourth and a flatted sixth. The F# Super Locrian mode consists of the notes F#, G, A, B♭, C, D, E and F#.

Here’s what it sounds like:

This sequence is also called the Locrian ♭4. Every degree is altered, which is why this sequence is also known as the Altered scale. You’ve probably heard it in Björk’s “Army of Me” or the intros to Rush’s “XYZ” and Metallica’s “Enter Sandman.”

Here’s another example of the Super Locrian sound:

OPEN YOUR EARS

Yes, it’s a lot of information … and it’s only the beginning. The best way to absorb all of this is to keep playing until you can hear each scale before you play it. Map the chords on a keyboard if you have access to one, outline the arpeggios on your bass, and let your ears guide you. The finer points of when to use each scale can wait; for now, enjoy the sound and the stretch.

Note: All audio clips played on a Yamaha BBP35 bass.