A Bassist’s Guide to Reading Sheet Music and Tablature

It’s easier than you think.

Reading and writing music is the fastest way to understand and communicate musical ideas. For a bass player, the sheet music for any given song (a “chart”) conveys a boatload of valuable information, including a composition’s key, tempo, style, chord progression and various endings. Back in the old days, most bass players learned by reading and writing charts, but today, we learn from MP3s, YouTube and Spotify, as well as software that can help us isolate a bass part, slow it down, loop sections and tell us what the chords are.

If you aspire to be a professional, however, reading music is a must. In situations where budgets and timelines are short, knowing how to read can make all the difference, helping you instantly see the contour of a bassline, understand its components and put it in context, which gives you options for improvisation. If you’ve avoided learning how to read because you think it’s difficult, remember that there was a time before you could read these words, too — and now you hardly think about it.

PITCH

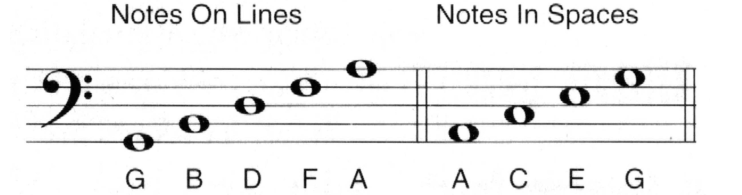

The core elements of a bassline are rhythm, rest and pitch. In standard notation, music for guitar and many other instruments is written in treble clef, but music for bass — including electric and acoustic bass, a keyboardist’s left hand, as well as bassoon, trombone, and tuba — is usually written in bass clef. (Piano notation uses both clefs.) Each line and each space of the staff (the section that follows the clef) represents a pitch, and notes are indicated by oval-shaped dots, sometimes open, sometimes closed, like this:

If it helps, use a mnemonic like “good boys do fine always” or “all cows eat grass” to remember the notes on the lines and in the spaces.

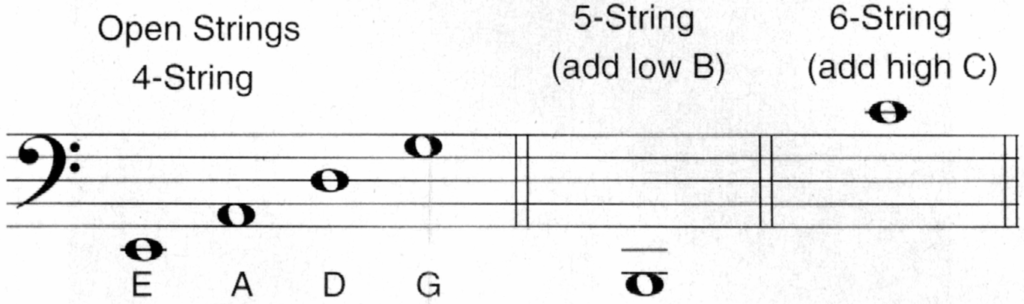

Next, let’s look at the pitches of the open (unfretted) strings on bass.

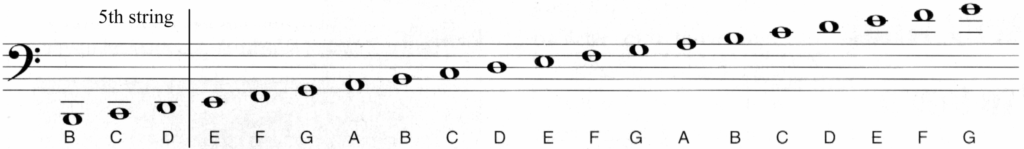

Notice that the open E, the low B and the high C don’t fit on or between the five lines (called the system). Those notes (and many others) require ledger lines above or below the standard five lines. For example, here’s the way every note on a 5-string bass is represented in notation, from an open B string all the way to the 21st and final fret:

KEY AND TIME SIGNATURES

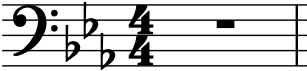

The top left corner of any piece of sheet music contains crucial information. To the immediate right of the bass clef you’ll find the key signature, which may contain accidentals (sharps or flats) to tell us what key the song is in.

The key signature in the example shown above has three flats that, as the chart below indicates, means the song is in E♭ major. As we go around the circle of fifths shown below, we gain accidentals. In the flat keys, we start with F (one flat), move up a fifth to B♭ (two flats), go to E♭ major (three flats), and so on. (As you can see, this chart also includes the relative minor keys [those that share the same key signature with the relative major keys].)

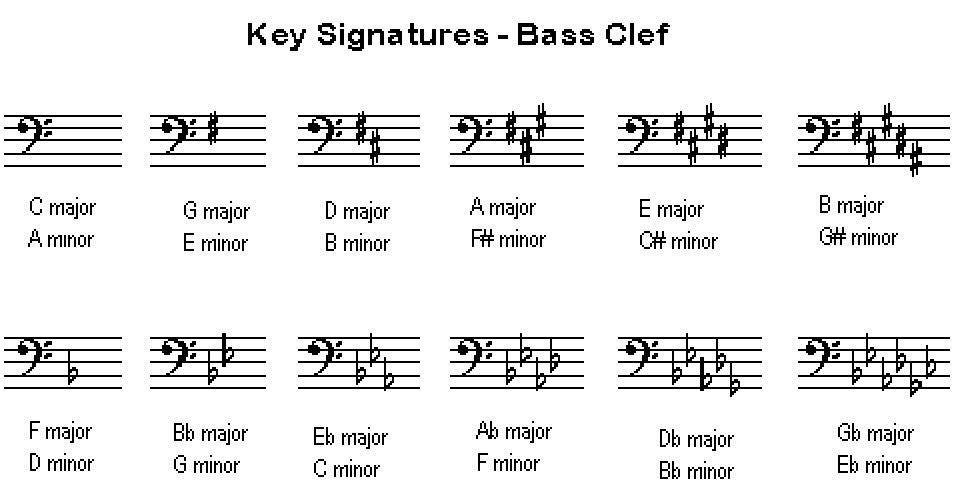

To the right of the key signature is the time signature: two numbers that tell us how many beats there are per measure (the top number) and what note gets the count (the bottom number). In the 4/4 time signature shown above, each measure has four beats. Simple math tells us that a whole note equals two half notes, four quarter notes, eight eighth notes and 16 sixteenth notes. Whole notes are represented by a hollow dot; half notes are also hollow dots, but with a vertical stem (upward- or downward-facing) added; quarter notes are represented by a solid dot with stem added; eighth notes are similar to quarter notes but with a single-line horizontal beam placed above or below; and sixteenth notes are similar to eighth notes but with a double-line beam added:

4/4 is the most commonly used time signature; other popular ones you’ll encounter include 3/4 (waltz time), where there are three quarter-notes in a measure, and 6/8 (blues shuffle), where there are six eighth-notes in a measure.

Notes tell us what to play and rests tell us how long to be silent. Whole notes and whole rests last four beats; half notes and half rests last two beats, etc.:

RHYTHM

Reading rhythms takes practice, but it can be fun. Start by counting each quarter note as “one,” eighth notes as “and” and sixteenth notes are “one-e-and-ah.” Using common words with the same number of syllables can help you understand how rhythms look and sound, as follows:

Count “one two” (“hot dog”).

Count “one two-and” (“grape soda”).

Count “one-and two” (“apple pie”).

Count “one-and two-and” (“hot fudge sundae”).

Count “one-e-and two” (“coconut shrimp”).

Count “one-and-ah two” (“Rice Krispie treat”).

Count “one-and two-and-ah” (“peanut strawberry”).

Count “one-e-and two-and” (“cinnamon oatmeal”).

Count “one-and two-e-and” (“milk and cereal”).

Count “one-e-and-ah two” (“avocado toast”).

Count “one two-e-and-ah” (“cheese ravioli”).

Count “one-and-ah two-and” (“strawberry ice cream”).

Count “one and two-e-and-ah” (“chips and guacamole”).

Count “one and two, three and four” (“tater tot, tater tot”)

Count “one-e-and-ah two and” (“pepperoni pizza”).

When I play these 14 figures on the G (third fret of the E string) on my vintage Yamaha BB2000 four-string bass, it sounds like this:

LET’S DANCE

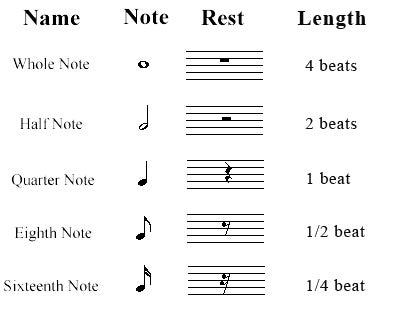

To see all this in action, let’s look at Ron Mollinga’s transcription of the main groove for Carmine Rojas’ classic bassline for David Bowie’s 1983 monster hit “Let’s Dance.” (Mollinga is the founder of the Bass Transcribers Facebook group.)

Mollinga packs lots of info into this eight-bar segment. The key signature tells us that the song is in either D♭ major or B♭ minor (judging by the first note of the bass line — as well as the chord symbols — B♭ minor is a safe bet). The lowest note of the bass line is an F and the highest is the high E in bar 4, so placing your fretting hand’s index finger on the first fret of your E string is a good place to start. The dots underneath the first four notes (and in other measures) direct us to play the notes solid and staccato (Italian for “detached”); the “f” underneath the first note, which stands for the Italian word forte (strong), directs us to put some muscle on that B♭; and the bar numbers help us keep our place in the chart. Notice that a slide connects the last note of bar 4 and the first note of bar 5. Note duration is crucial, so heed the rests.

TABLATURE

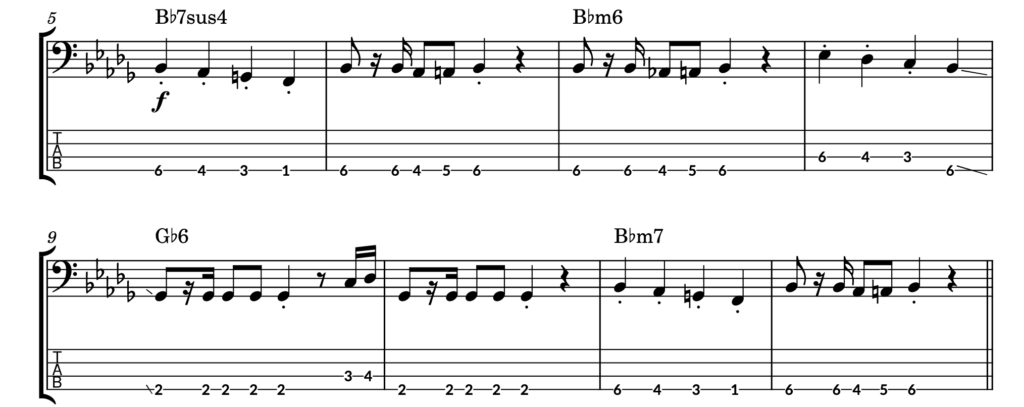

This next transcription of the same bass line adds tablature (usually shortened to just “tab”) beneath the standard notation:

Although tab is popular among bass players who don’t read notation, many musicians consider it a shortcut that doesn’t pay off in the long run: It tells us where to fret the notes and on which string, and it can be helpful when notating techniques like hammer-ons, pull-offs, slides and bends, but it lacks any information about rests, rhythm, note length or expression. If you only read tab, you’re missing out on lots of great music literature; what’s more, used alongside notation, it offers a solid starting point for fingering.

Here’s an isolated recording of Rojas’ bassline without the synth line that doubled it on the original recording.

CHORD CHARTS

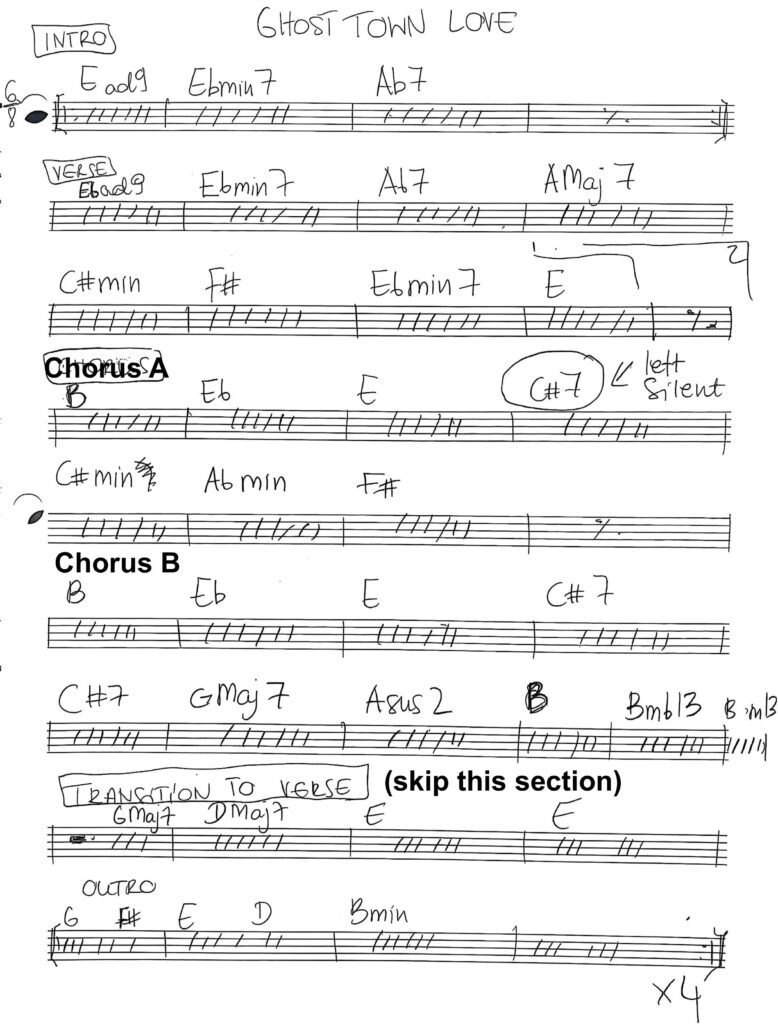

Chord charts are far more basic than even tablature. This chart, hastily written by a pianist for a song called “Ghost Town Love,” is a typical roadmap that leaves lots of decisions up to the bass player.

Some things to notice at first glance: The time signature, 6/8; the sections (intro, verse, chorus, transition to verse, and outro); and the “left silent” direction in bar four of chorus A. Most systems are four bars, but the numbered brackets at the end of the verse tell us to add a bar of E when we play the verse for the second time (there are also two “extra” bars at the end of chorus B). The arrangement goes like this: Intro, verse 1, verse 2 with the extra bar, chorus A, chorus B, back to intro, verse 3, verse 4 with the extra bar, chorus B, outro.

Here’s the “Ghost Town Love” demo with just drums and piano:

And here’s what it looks and sounds like when I add a Yamaha BB435 5-string bass with both pickups all the way open:

Even without notes, tab, a key signature, a tempo or bar numbers, this chart had enough information for me to play bass on the demo, and a short conversation with the pianist cleared up whatever questions I had. I tried to put some emotion in the bassline, but I kept it simple, leaving space and mostly playing passing notes, as well as roots, fifths, and octaves. Walking up the E major scale before chorus A (at around the 0:44 mark) and the F# major scale at the end of chorus A (2:03) seemed appropriate, as did a slightly different tone for the second intro (1:27). I had fun reacting to shifts in the piano part, and if there had been a more dynamic drum part, I would have tailored my part to suit it. Reading the chart meant I didn’t have much time to look at the neck, which is why I found all the notes without moving my fretting hand lower than the third fret or higher than the seventh.

KEEP ON READING

Like anything, reading music gets easier the more you do it. Ron Mollinga and many others offer free bass transcriptions online; some more reliable than others, but each chart gives you a chance to practice your reading. Find the sheet music for music you love, follow along, and watch your reading skills — as well as your playing— blossom.