Bass Fingering 101

Choosing where to play the notes.

The longer you play bass, the more you’ll recognize the value in knowing where the notes are on your fretboard. Most modern 4-strings have at least 21 frets; some, such as Yamaha TRBX Series and RBX Series models, have 24 frets, allowing you to play 31 different notes.

Knowing where each note is may seem impossible at first, but fortunately, the layout of a bass makes it easy to move shapes around the fretboard. If you know how to play a major scale, for example, playing it in different keys is as easy as changing your starting note. Compare that to piano, where each of the 12 scales has its own fingering. We’ve got it easy!

SAME NOTE, DIFFERENT POSITION

With the exception of the five lowest notes on a four-string in standard tuning (E, F, F#, G and G#), every note can be played in at least two or three different places on a bass fretboard. The lowest A, for example, can be played on the fifth fret of the E string, or by simply playing the A string without fretting it (what’s known as an “open” string). The lowest D can be played on the fifth fret of the A string or as an open D string … or even on the tenth fret of the E string.

So if it’s the same exact note, it doesn’t matter where on the fretboard you play it, right? Wrong.

Try it out for yourself. Play that low A in both positions; play that low D in all three positions. As you can hear in the audio clips below, they all sound slightly different. This is mainly due to the different thickness of the strings. Thicker strings generate more fundamental (the lowest part of the note being played, which makes the sound “fatter”) and fewer harmonics (the overtones that impart brightness and make the signal more “edgy”).

Here’s the same note (G) played in four different places: at the fifth fret of the D string, the 10th fret of the A string, the 15th fret of the E string, and the open G string:

Here’s a descending groove that alternates between landing on a low A played on the E string and the same low A played on the open string. Notice that the fretted A doesn’t sound as, well, “open” as the unfretted A string.

Similarly, here’s a pattern that alternates between a low D played first on the fifth fret of the A string and then on the tenth fret of the E string:

If you need any further proof of this concept, check out The Beatles’ “Rain,” where Paul McCartney gets an incredible bass sound by playing most of his part — even some of the lowest notes — way up high on the fretboard, mostly on the thicker E and A strings. Motown bass legend James Jamerson, who influenced McCartney and many others, was the master of using open strings in places where most of us would choose fretted notes, as you can hear in these isolated bass tracks of him playing on the Temptations’ “Can’t Get Next to You” and Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On.” (Ready to watch a master at work? Here’s a rare clip of Jamerson performing the song live onstage with Gaye.)

And of course, as we described in a previous posting, octaves sound quite different altogether, and the sonic variation will become equally striking as you experiment with playing those octaves on various strings and in different fret positions.

LIFT AND SHIFT

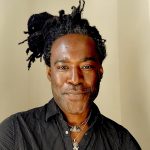

The easiest way to feel the power of shapes is to move one around the fretboard. As an example, let’s explore the G major scale. Now, this scale could be played all on the low E string, like this:

Here’s what it sounds like, played on my Yamaha TRBX174EW four-string bass:

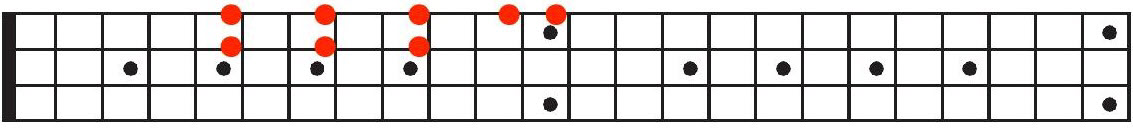

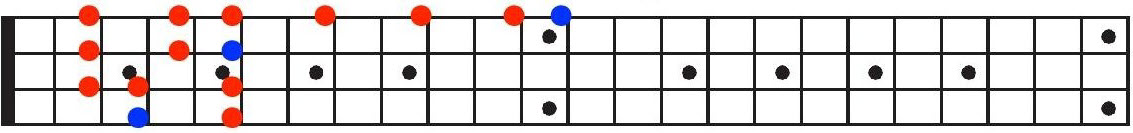

This has the advantage of sonic consistency since you’re playing all the notes on the same string. But there’s a much easier way to tackle a scale with much greater economy by having just four frets under your fingers instead of all 24 … and I’m happy to report that most bassists play it that way. The illustration below shows how it works with a G major scale: You start with the second finger on the low G (third fret on the E string), followed by the fourth finger on the A (fifth fret on the E string), first finger on the B (second fret of the A string), second finger on the C (third fret of the A string), fourth finger on the D (fifth fret of the A string), first finger on the E (second fret of the D string), third finger on the F# (fourth fret of the D string), and the fourth finger on the octave G (fifth fret of the D string).

This fingering starts on the lowest G of a standard-tuned bass, and it’s where most of our bandmates expect us to play it. Again, here’s what it sounds like, played on my Yamaha TRBX174EW:

As you can hear, there’s quite a sonic difference between the first two notes in the scale, the next three, and the last three, due to the fact that the E, A and D strings are all of different thicknesses (as is the G string, which is the thinnest of them all).

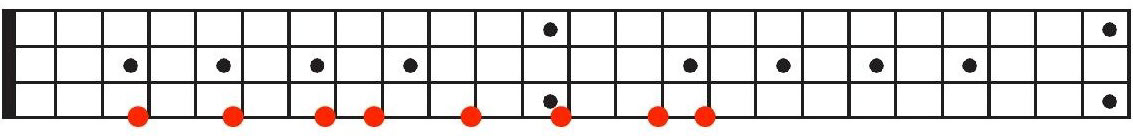

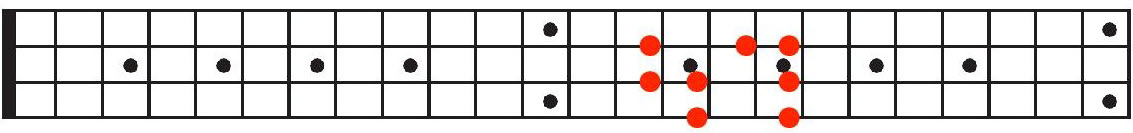

The illustration below shows a variation of the same theme. Despite playing the same scale and the same notes, it has a slightly different tonality and is more of a stretch since this “spread” fingering starts with G under your first finger, your third finger on A, and your pinky on B.

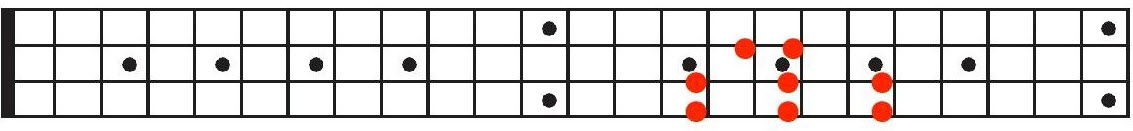

Shapes like these may fall naturally under your fingers, but sooner or later, you’ll have to lift your hand to shift to another position, so it’s worth practicing your ability to shift smoothly. Once you’ve climbed up the octave, you could play the G major scale as shown in the illustration below, with a fingering that requires a shift to play F# and G with the first two fingers, the last two fingers, or by sliding from one note to another.

Mining for Gold

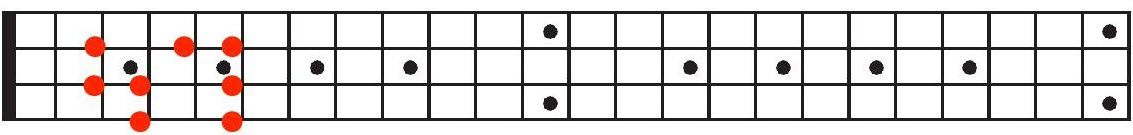

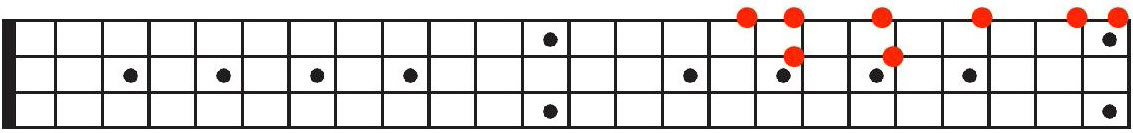

Of course, you can play these same scales all past the 12th fret, though this is foreign territory for many bassists. There’s gold in those hills, though, because particularly when played on the E string (which of course is the thickest string), notes have a certain resonance that makes them desirable. Here are a few examples of playing a G major scale way up on the fretboard. Note that the last two can only be played on a 24-fret bass.

As a bonus, playing scales high up the neck are somewhat easier to finger because, as you move toward the bridge, the space between the frets gets smaller.

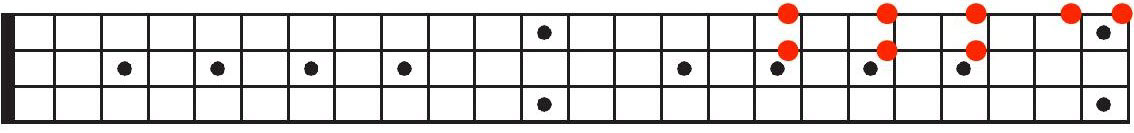

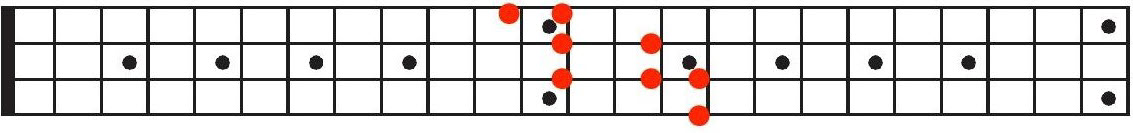

You can also play scales beginning on a digit other than your first or second fingers. As an example, try starting the scale shown in the illustration below with your fourth finger before shifting to play the last two notes on the G string.

Two-Octave Scales

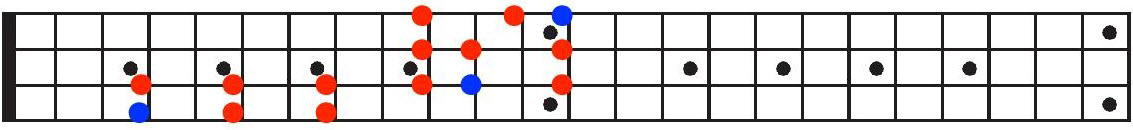

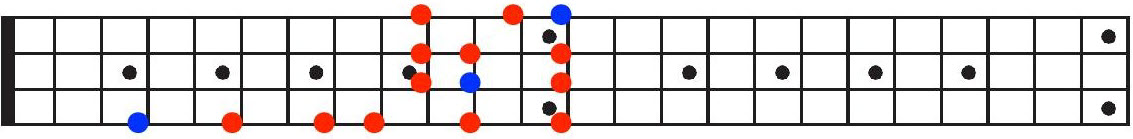

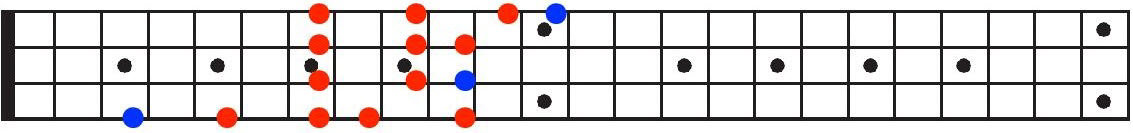

Once you’ve explored the many ways to play a one-octave G major scale, it’s only natural to connect two shapes to get a two-octave scale. The illustrations below show four ways of building a two-octave G major scale on your bass; the blue dots make it easy to see where your Gs are.

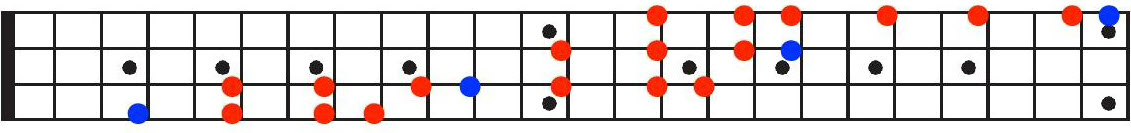

Finally, here’s a way to get all the way from the lowest G to the highest G by playing a three-octave scale, though this can only be played on a 24-fret bass:

As you can hear clearly on this last audio clip, the timbre changes quite dramatically as you go from the notes played on the E string to those played on the A, D and G strings, with the latter having much more “edge” due to the relative thinness of the G string as compared with the other strings.

Playing through these examples should give you the confidence to find G major anywhere on your neck; do the same thing with G minor, other keys and other modes, and be sure to ascend and descend each pattern.

Last but not least, be prepared to break the “rules.” Many bassists are taught to use one finger per fret, but you should decide what fingerings work best for your hand and your bass’s neck. Some fingerings are obvious, but others are open to interpretation. Trying different approaches will help you find your own method and will prepare you to think fast and make big leaps — both valuable tools when it comes to holding down the low end.