Getting Your Bass Into the Groove

Secrets of finding (and staying in) the pocket.

“Groove!”

For many bass players, it’s a sacred commandment, a call to action and a mission statement more important than technique, gear, music theory, wealth or (in some select cases) personal hygiene. Being complimented on one’s groove by another musician is the highest form of praise, and anecdotal studies have demonstrated that bassists who know how to groove get more gigs and generally live better lives. But can you define “groove”? And can anyone develop it?

The answer to both questions is a resounding yes.

KNOW IT AND GROW IT

“Groove” is the heartbeat and pulse of a piece of music. It transcends genre: Beethoven symphonies, Burt Bacharach tunes, Black Sabbath riffs, Dave Brubeck standards, B.B. King classics, Bad Bunny bangers, Blake Shelton sing-alongs and Beyoncé jams all have that oh-so-persuasive rhythm that makes it hard not to shake our hips, snap our fingers and nod our heads.

As bass players, it is our job to understand the right groove for each situation, which requires honing our “feel” — intuition plus knowledge, fine-tuned by experience — and settling into the pocket with the rest of the band. The best way to develop your relationship to the language of groove is to listen deeply to those whose grooves inspire you, while paying close attention to the way that masterful musicians support the flow of energy in a given piece of music.

PRACTICE TIPS FOR GETTING IN THE GROOVE

Developing a strong relationship with time by playing scales, chords and bass lines using a metronome like the Yamaha MP90 provides a great foundation for grooving. Many of us naturally play in front, on top of, or behind the beat, so work on whatever doesn’t come naturally. Rock bassists, for example, are frequently asked to play ahead of the beat, while reggae bassists are best known for playing behind the beat.

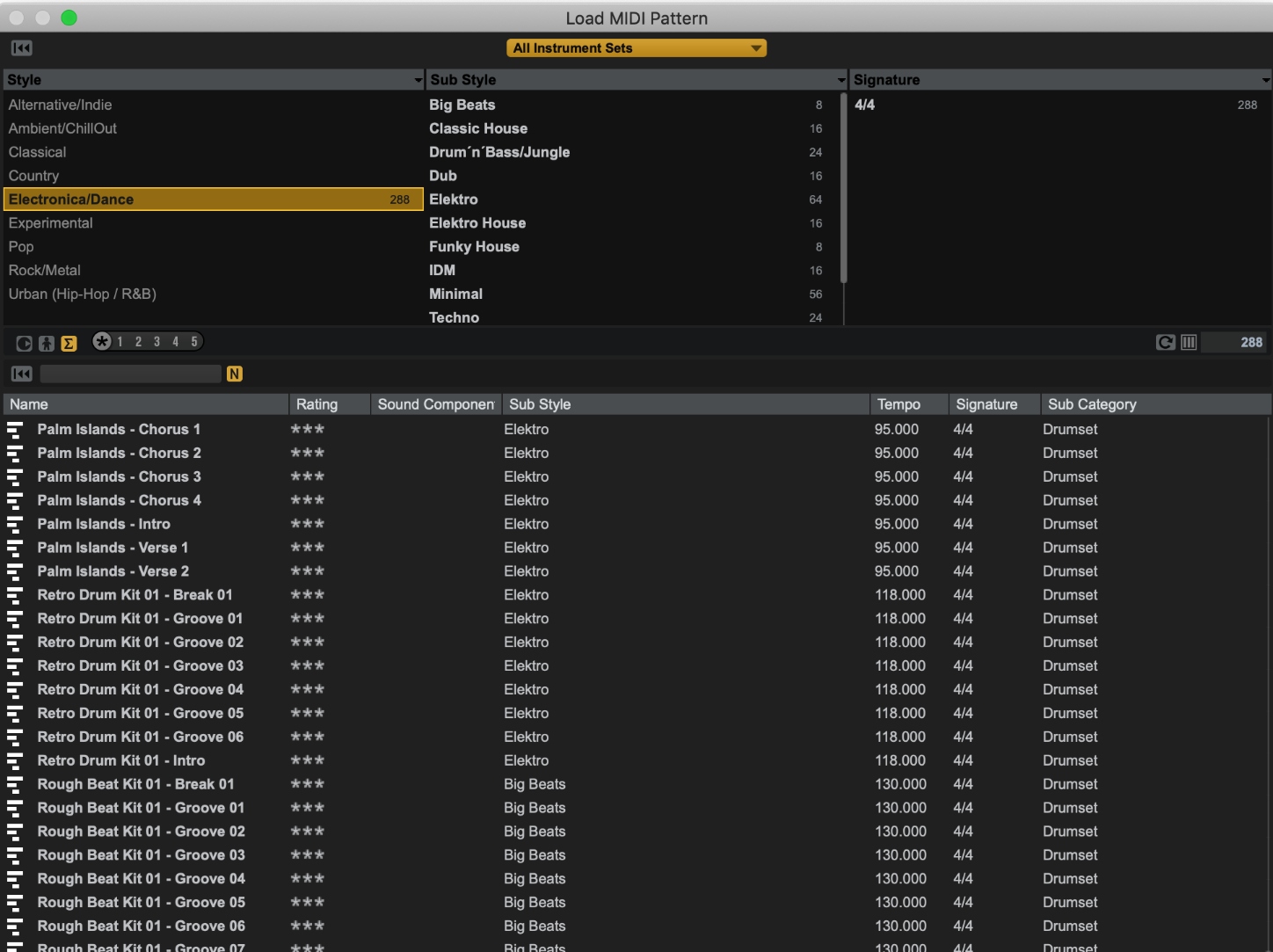

That said, playing with a drum loop is a lot more fun and interactive than working with a metronome, plus it’s a great way to refine your relationship to the kick drum — every bass player’s best friend. Most digital audio workstations, including Steinberg Cubase, offer plenty of beats to choose from. There are also plug-ins like Groove Agent SE (included with Cubase) that provide collections of audio loops of realistic sampled drum sounds, as well as MIDI loops (in Groove Agent SE, called “patterns”) that allow you to change the drum sounds at will. These kinds of apps make it easy to play along and refine your relationship to the groove without a live drummer.

But as much fun as it can be to jam with virtual drums, the bassist’s primary job is to connect rhythm and harmony, so the most important thing is to practice along with actual music. Playing along to tracks you love is a great way to understand how the players you admire groove in particular situations. I have a collection of albums without bass parts — everything from piano/drum duets to Middle Eastern percussion ensembles — and I enjoy the challenge of finding the right notes and rhythms without the benefit of sheet music or chord charts.

Finally, recording yourself and listening back is like looking into a mirror that clearly reflects your strengths and weaknesses. As you listen, take notice of your rhythmic impulses. Working on your weaknesses and cataloging your strengths will pay huge dividends when you do play with a live drummer.

THE RHYTHM SECTION

Having a conversation with a drummer through music is one of the great joys of being a bass player, especially when you listen to each other. Your drummer may feel things differently than you do, so don’t be afraid to talk it out. If you’re still not gelling, start by simplifying your bass part and following the kick drum. Being part of a rhythm section that’s in sync is one of the best feelings in the world, but tension can be juicy, too, as long as it serves the music.

As you settle in with your groove partner, here are some ways to take care of business on bass:

- Tone. Supporting the rest of the band with a strong, confident approach helps everyone groove.

- Time. Rushing (unintentionally playing ahead of the beat) or dragging (unintentionally playing behind the beat) can kill the groove.

- Dynamics. Learning when and where to turn up or play delicately is crucial.

- Silence. Knowing when to lay out is important, too. If the groove is in jeopardy, simplify.

- Note length. Being purposeful about playing short notes or long ones can make all the difference.

- Ghost notes and dead notes. Ghost notes are low-volume notes played between main notes as part of a phrase, while dead notes are “thumps” with no discernable pitch. Knowing how to use these options helps make something “funky.”

- Repetition. If you’ve been to a dance club, you already know that repetition makes your body move.

- Relax! Being self-conscious and uptight makes it harder to give the music what it needs.

- Genre. To relax and groove, you must be familiar with the genre you’re playing in.

AUDIO EXAMPLES

To illustrate these concepts, here are some audio clips that feature a guitar riff accompanied by a drum loop, then by real drums. First, I provide a “minus-one” version, followed by the same clip with me grooving along on bass. Note that spacious rhythm section parts reveal different aspects of the guitar line, and also take note of how each drummer’s phrasing changes my approach.

Here’s the first example without any bass:

… and here it is with me playing a Yamaha TRBX174EW 4-string bass with the E string tuned down to D. As you can hear, I’ve added a sturdy melodic figure next to the drum loop, switching to whole notes and then octaves on the way out.

Here’s example 2, minus any bass …

… and here it is with me again playing the TRBX174EW, this time in standard tuning. My approach here was to match the syncopation of the drummer’s off-kilter part, lean into his triplets, and then go up the neck.

Next, example 3, minus any bass …

… and here it is with me playing along on a Yamaha BB435 5-string, sitting in the pocket with the side-stick pattern, and then going to eighth notes on top of the beat when the drummer switches to the ride cymbal.

Finally, example 4 with no bass …

… and the same clip with bass added, also played on the BB435. Here, I hug the kick drum for the first section, play long tones over the syncopated groove, and then meet up again as the drummer gets busier.

THE BIG PICTURE

Groove can be a slippery concept, but learning to articulate and refine it helps us do our job as bassists, which is to be fully present to whatever the music needs. Once you’ve internalized the elements discussed above, you’ll be better prepared to give in to the music — which will make your drummer, the rest of the band and the audience groove until the proverbial cows come home.