Which TransAcoustic Guitar is Right for Me?

There are six distinctive models to choose from. Here’s how they differ.

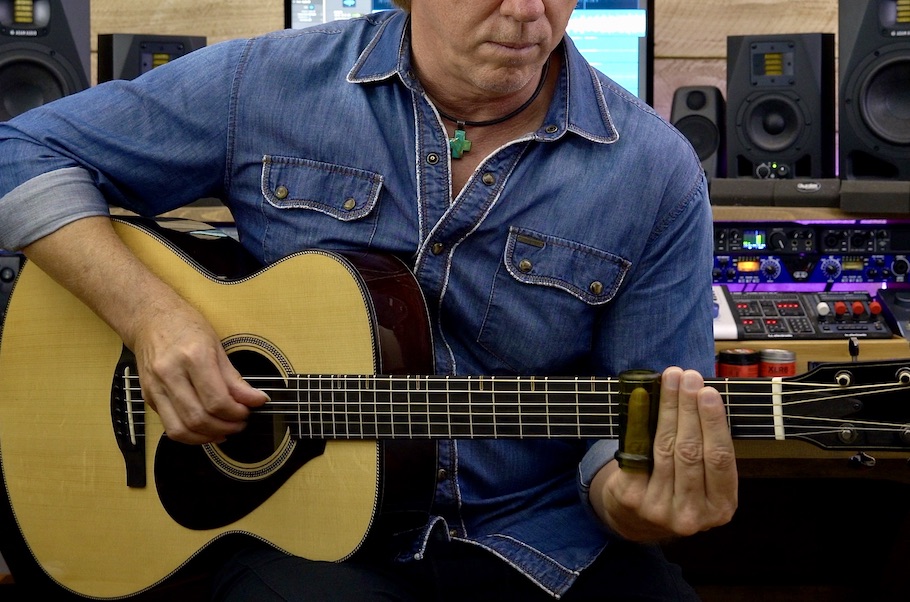

The first time you play a Yamaha TransAcoustic guitar can be a surreal experience. It certainly was for me! A couple of years ago, I was visiting the recording studio of a friend who had just come into possession of an FG-TA model (I’ll explain the differences between the various models shortly). I picked the instrument up and inspected it. To my eyes, it simply looked like a really nice acoustic guitar. That’s what it sounded like too, as I began playing. But with one press of a small button on the guitar, everything changed; that very same instrument now sounded like it was being played in a concert hall, with a lush, almost tangible reverb lingering after each note.

I’d read a bit about the company’s TransAcoustic technology, so I wasn’t completely unprepared for this. But even so, I found myself looking around the room for a hidden amplifier or a wireless connection to a remote pedalboard. Of course, there was none to be found: What I was hearing was coming straight from the guitar’s body. Not that TransAcoustic guitars can’t be plugged into an amp (they can, via a handy jack that carries the signal from an onboard piezo pickup). But the only thing a guitarist has to do in order to access that reverb and an equally lovely chorus effect is to simply play the instrument.

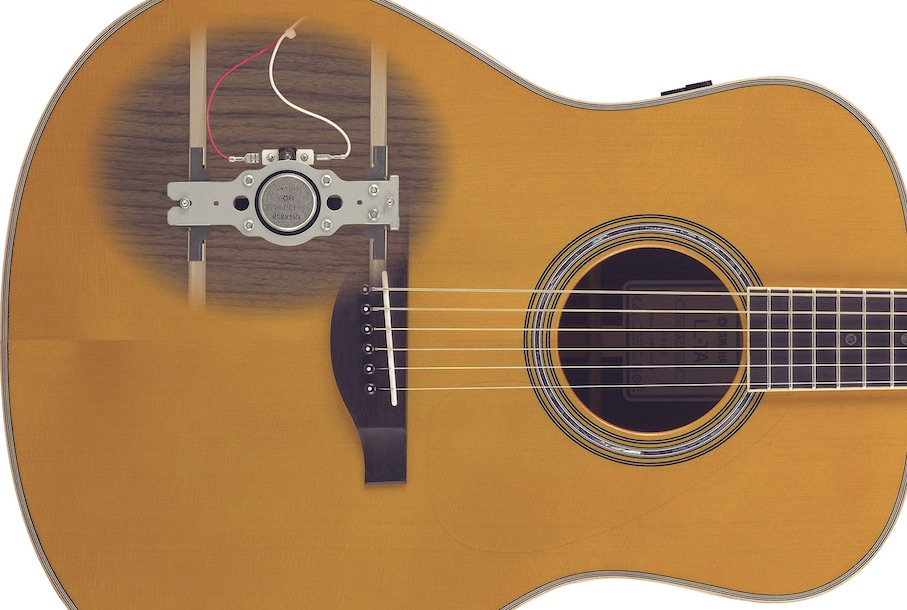

The secret of the TransAcoustic sound is a device called an “actuator” that’s attached to the inner back of the instrument. When you play the guitar, the actuator picks up the vibrations of the body and adds its own — vibrations that, through a kind of sonic translation process, become effects. Knowing this secret, however, doesn’t do anything to diminish the strange magic being produced.

As surreal as that first experience is, you quickly get used to it. And being able to aurally expand the size of the room you’re playing in, with no cables or plugs involved, is a pretty cool trick. But if you want to have that experience for yourself (and I heartily encourage it), you may be wondering where to begin. That depends on where you’re at as a player and what you prefer in your guitar. Here’s a rundown of the six current TransAcoustic models, so you can make a more informed decision.

LL-TA and FG-TA

Standard-size acoustic guitars (also known as Western-body guitars or dreadnoughts) are bright and loud, with a pronounced bass resonance, perfect for strumming out big chords in rock, folk, and country music. Yamaha offers two standard-size TransAcoustic guitars: the LL-TA and the FG-TA. The differences between them mainly come down to the types of wood used and the way their bodies are braced (the bracing allows the top to vibrate while still keeping it stable).

The LL-TA has a solid Engelmann spruce top that’s been treated with a Yamaha process called A.R.E. (Acoustic Resonance Enhancement). One reason why vintage acoustic guitars can be so highly prized is that the tone produced by many woods tends to get richer over time. A.R.E. aims to replicate that quality in a new instrument. The LL-TA has a rosewood back and sides, and its bracing is non-scalloped, meaning that the pieces of wood used to brace the top are fairly uniform in their dimensions; these features equal a brighter, more direct sound. (Here’s a video of the LL-TA in action.)

The FG-TA has a solid spruce top (with no A.R.E. treatment), a mahogany back and sides, and scalloped bracing. Mahogany tends to impart a dark tone, and scalloped bracing — created by shaving away or even simply removing parts of the wood braces inside the instrument — allows the top to vibrate more, creating a kind of halo around notes and chords. The result is a deeper sound; one might even call it a little mysterious.

LS-TA and FS-TA

Concert-size models are my personal favorite type of acoustic guitar. Their bodies are smaller than standard size, and they’re more suited for music that’s intricate and detailed. Bluegrass, blues and folk players — particularly guitarists who like to fingerpick — often have a special relationship with concert-size acoustics.

Yamaha makes two concert TransAcoustics: the LS-TA and the FS-TA. The differences between them are the same as those between the LL-TA and the FG-TA: Engelmann spruce top with A.R.E. versus standard spruce top, rosewood versus mahogany back and sides, and non-scalloped versus scalloped bracing. The bodies of both instruments are about an inch shorter than their standard-size counterparts.

CSF-TA

A parlor guitar is even smaller than a concert-size guitar. Considerably smaller, in fact — the fingerboard of the CSF-TA is 23 5/8″ long, as opposed to just over 25″ on all other TransAcoustic models, and the instrument’s total length is 37″, at least two inches shorter than any other TransAcoustic. As you’d probably expect, the sound produced by a parlor guitar is more intimate than that of its larger brethren. If you’ve got big hands, the CSF-TA may not be for you, but if you prefer your guitars quiet, cute and easily embraceable, there’s no better choice. Like the FS-TA, the CSF-TA has a solid spruce top and mahogany back and sides.

CG-TA

I generally encourage beginning guitarists to start out on a classical instrument, for two reasons: First, the nylon strings of a classical guitar are easier on the fingers than steel strings in the early stages (i.e., before you develop calluses), and second, the wider neck of a classical makes for an easier transition to a narrower neck characteristic of a steel-string guitar if and when you want to move on. Not that there’s any actual need to make the change; some players never want to stop playing classicals once they’ve started. Their deep, dark tone and roomier fingerboard make them ideal for classical repertoire, of course, as well as for Spanish flamenco, Brazilian bossa nova and American folk music. The CG-TA incorporates TA technology into a classical guitar. It has a spruce top, ovangkol back and sides, and a neck that’s only about 3/8″ thicker than steel-string TransAcoustic models.

No matter which of these instruments you choose, you’re bound to enjoy the array of tones they place at your disposal — not to mention the surprised reactions those tones may elicit from listeners. If you find that members of your audience start making furtive, puzzled glances around the room as you begin playing, my advice is to just give them a big smile … and keep playing. Chances are you’ll soon find your smile returned many times over!

Check out these related blog articles:

How Yamaha TransAcoustic Guitar Technology Works

Discover Yamaha TransAcoustic Guitars

MJ Ultra and the FG-TA TransAcoustic Guitar

“Breaking Amish” With My Yamaha FG-TA

How to Record TransAcoustic Guitar Effects

Click here for more information about Yamaha TransAcoustic guitars.