A Guitarist’s Guide to Reading Sheet Music and Tablature

Joining the dots.

I’m sure most of us, at some point, have contemplated learning a new language … even if it’s just a few key phrases to help us communicate during an exotic vacation.

There are an estimated 7,169 living dialects spoken in the world today. As guitar players, and as musicians, we also have several languages (fortunately, way less than 7,169 of them!) we can use to document, learn and share our music with others. The most commonly employed musical languages are:

- Formal notation

- Tablature

- Chord charts

- The Nashville numbers system

In this posting, we’ll take a look at each.

Formal Notation

Learning to read formal music notation can be a daunting task for many guitar players, and rightfully so. If you don’t understand the symbols, dots, stems and structures on the sheet of paper (technically called the manuscript), it all just looks like Egyptian hieroglyphics. However, there’s a difference between sight-reading, where you can decipher everything at a glance and play it as you do so, and basic notation reading skills, where you may need to review what’s on the written page several times before being able to play it accurately.

Developing the ability to sight-read music notation takes years of study and decades of dedication. If you have the desire to become a proficient sight-reader, you are most likely looking to forge a career that requires that very specific skill—for example, becoming a professional session player, orchestra pit member, transcriber, orchestrator or composer. For the rest of us, it’s sufficient to develop a basic understanding of the written idiom to help you learn, share and expand your musical knowledge.

Let’s start with the symbols, structures and signs that are used in formal notation and tablature.

The Stave and Treble Clef

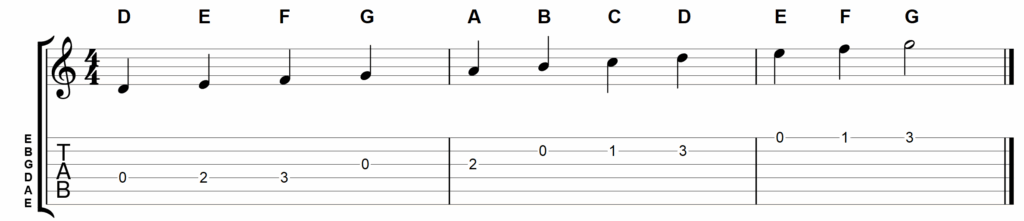

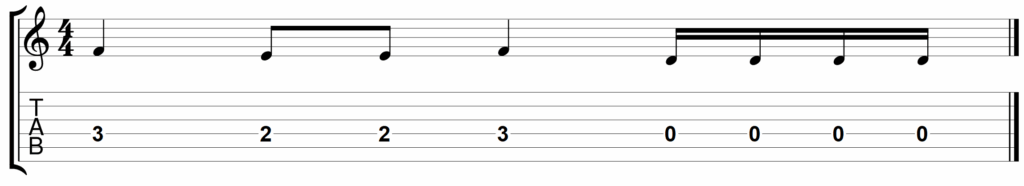

The illustration above shows typical guitar notation and tablature. The top line (called a stave) is the notation. As you can see, it’s made up of five horizontal lines. Each of those lines, and the spaces in-between, represent a musical pitch, as indicated.

Guitarists read music on a stave that’s called the treble clef, sometimes also referred to as the G clef. It’s depicted at the very beginning of the stave by a shape that encircles the second line up from the bottom. This clef is also used to depict notes to be played by the right hand on a keyboard. (There’s also a bass clef, which appears beneath the treble clef, but this is used to depict notes meant to be played by bass or by the left hand on a keyboard, so we won’t be showing it in this blog post.)

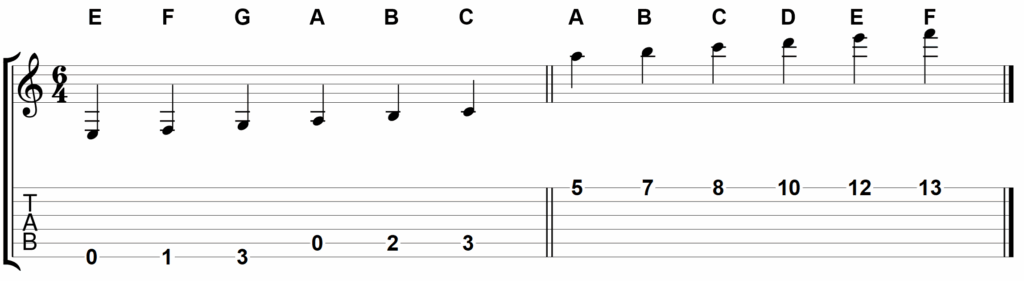

Ledger Lines

Ledger lines are short lines placed above or below the standard five-line stave that show notes that are higher or lower in pitch than the standard five lines and spaces.

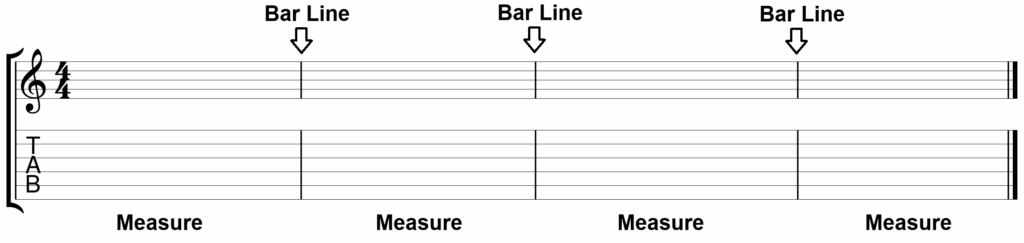

Bar Lines

The stave is divided into sections using vertical bar lines. These allow notes and rhythms to be grouped into smaller, easier to read sections called measures.

Time Signatures

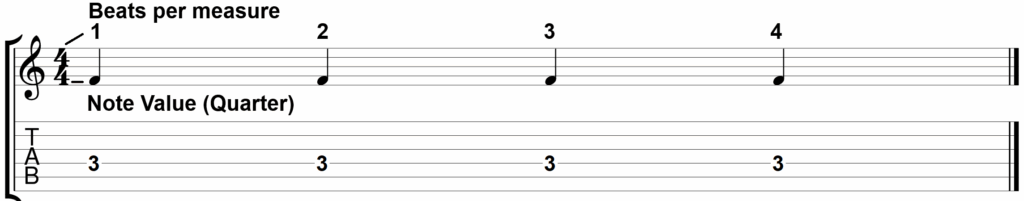

The time signature is placed directly after the treble clef sign. It defines the main pulse of a musical piece, and tells us how many of those main pulses are found in each bar (measure), as well as the note value that each main pulse receives.

The upper number describes how many main pulses are found in each measure, while the lower number describes the note value, or length of pitch each pulse will receive. In the example above, the “4” above the line tells us that there are four main pulses in each measure. The lower “4” tells us that each main pulse receives a duration of a quarter note. The four quarter notes ultimately add up to a whole note (one measure).

Pitch

Musical pitch is shown on the stave vertically using dots. These dots also define how long a pitch is to be sounded (i.e., the duration of the sound).

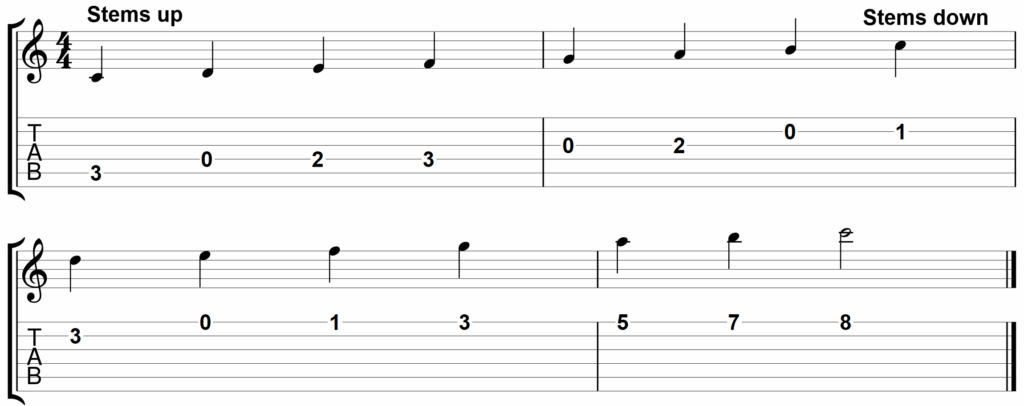

Rhythms are laid out in a linear, horizontal form. Stems are used to define the pitch duration. Those stems, when subdivided into smaller durations, can be joined together using beams; this helps to group notes together in each main pulse. These groupings of notes within a main pulse makes them easier to read. We’ll talk more about rhythm shortly.

Stem Direction

The stems attached to a dot that’s written on or below the middle line of the stave (the note B) are attached to the right of the dot, and point upwards. Stems attached to a dot written on or above the middle line are attached to the left of the dot, and point downwards.

Note Values and Rests

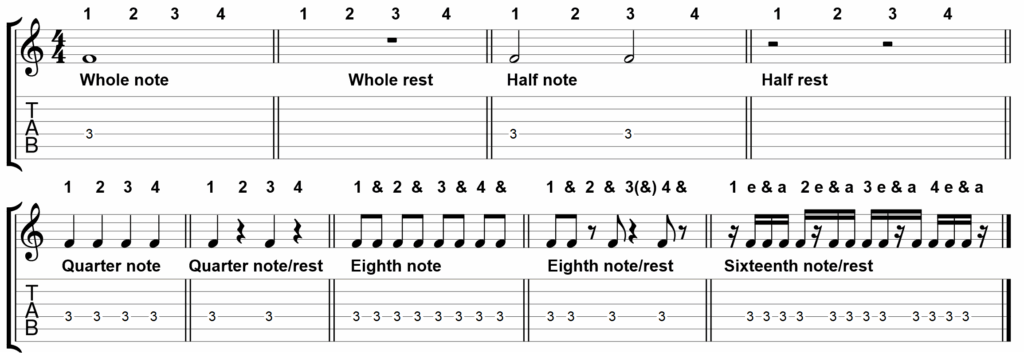

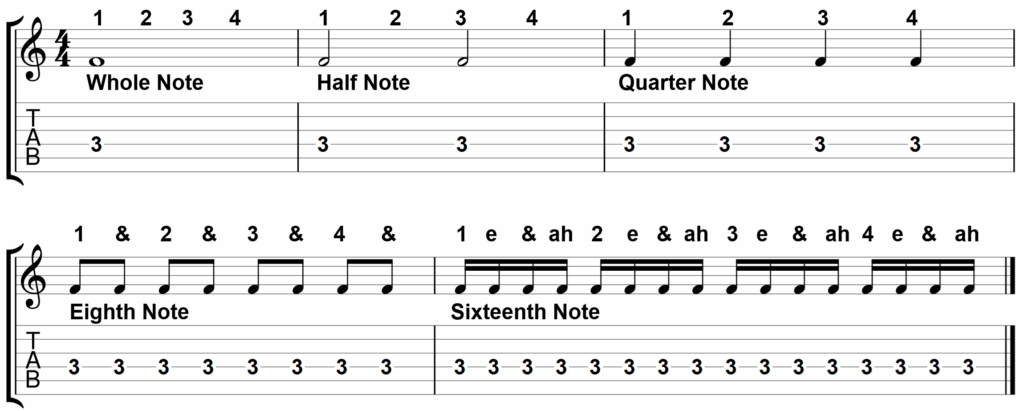

As we’ve seen, each dot represents a pitch, rhythm and sound duration. As shown in the illustration above, there is also a symbol that represents the equivalent in silence. These are called rests.

Now let’s look at the note values used in written music, and the ways they can be subdivided to create shorter sounds. This process creates rhythm in the music.

Rhythm

As shown in the illustration above, whole notes — the ones that are played and held throughout a whole measure — are the only notes that don’t receive a stem; they also have a hollow center.

A whole note can be halved by placing two hollow dots on the stave and adding a stem to each. These are called half notes.

Rhythmic values shorter than a half note are represented by a solid dot. For example, a quarter note is indicated by a stem attached to a solid dot; it has half the rhythmic value of a half note. That note duration can be halved yet again by adding a single tail to the stem to create an eighth note. Adding an additional tail to the eighth note results in a note duration of a sixteenth note, thirty-second note and so on, each played with half the duration of the preceding one.

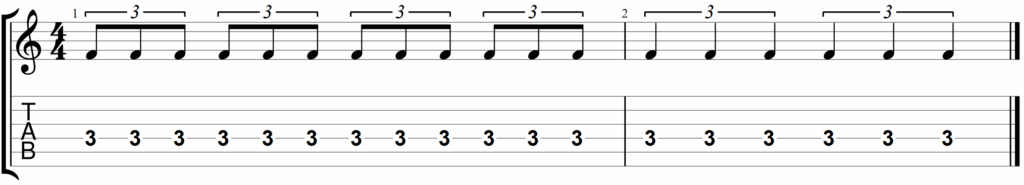

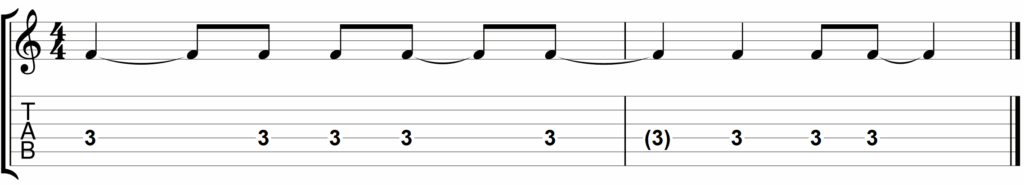

Brackets

Brackets are used to group triplets together. A triplet consists of three notes played in the space of an eighth note (as in the first measure above) or quarter note (as in the second measure above).

Ties

Curved lines called ties are used to join notes of the same pitch together. They’re used when you want to join notes at the end of a pulse to the note of the next pulse. You can also use ties to join notes across a bar line.

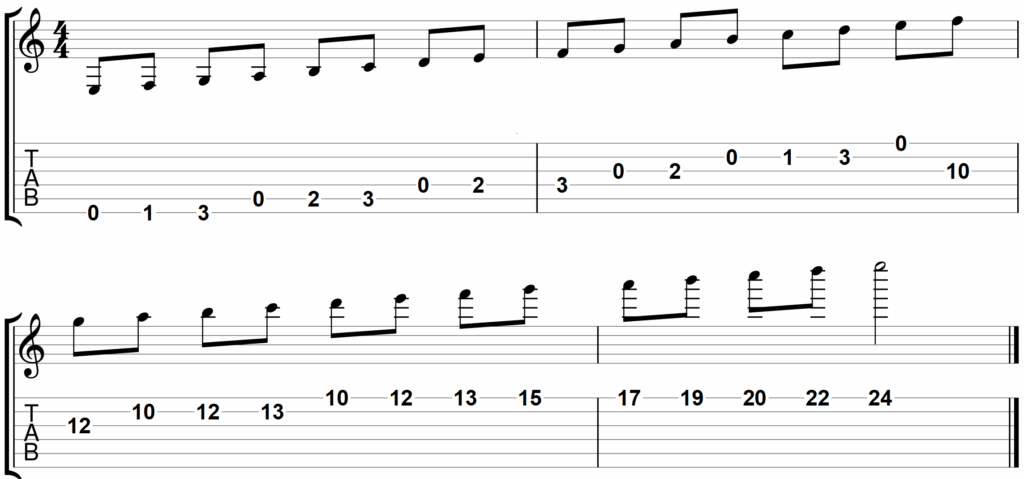

The Pitch Range of the Guitar

As shown in the illustration above, a standard six-string guitar with 24 frets provides a possible pitch range of four octaves. The low E-string is located below the stave on a ledger line, and the high E-string at the 24th fret would be shown on a ledger line above the stave.

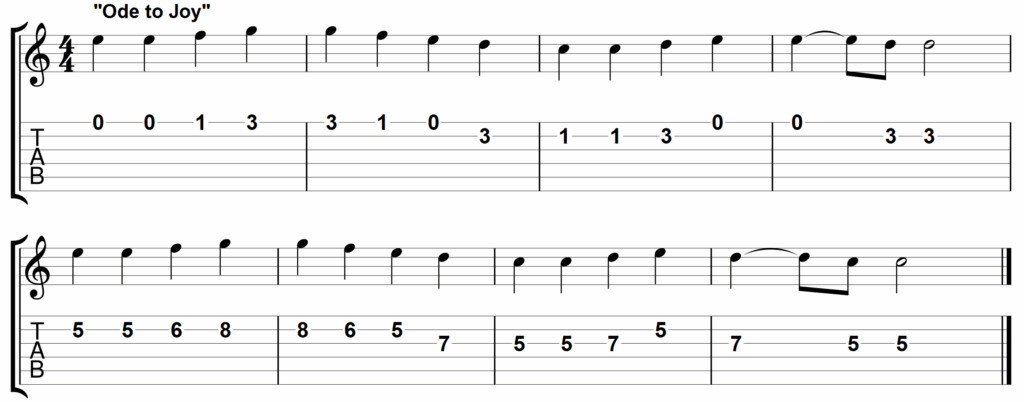

Guitar Tablature

Tablature (TAB) is usually written below the standard notation so that the bar lines, measures and rhythmic figures all line up. At first glance, guitar tablature looks very similar to the five-line musical stave; however, it has six lines representing the six strings of the guitar. (The low E string is on the lowest line.) Another difference is that the notes in tablature are indicated by numbers, not dots. The fret location number is written on the string on which it’s to be played, and placed directly under the rhythmic attack found in the standard notation. The great thing about tablature is that it defines exactly which string and fret location a note or phrase is to be played at. Often in standard notation, the music can be played in more than one fretboard location, which can be confusing.

To illustrate how it works, here’s a video of me playing “Ode to Joy” using the tablature above:

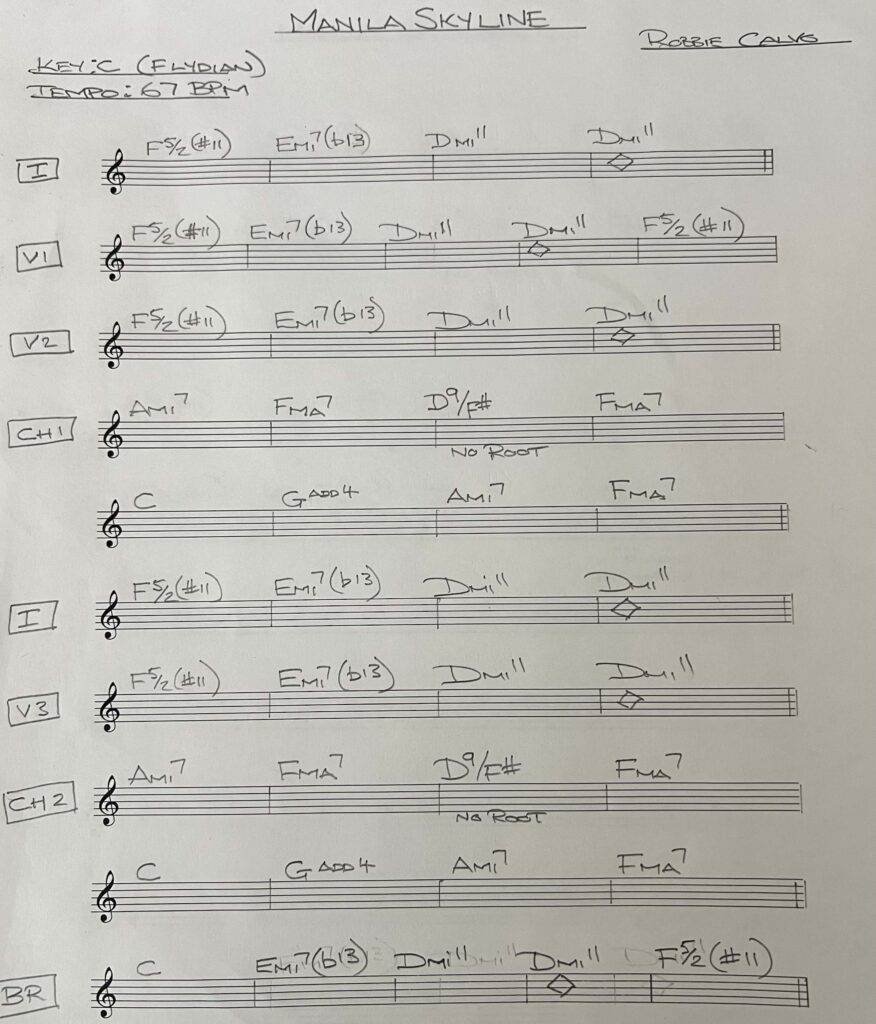

Chord Charts

Chord charts are written on standard manuscript paper, with the specific chord name placed above the top line of the stave. Specific rhythms may be written below the chord; if not, the player can interpret the rhythm however they choose. Reading chord charts requires a good knowledge of harmonic structures and chord types.

Chords are often included on a manuscript that includes both notation and tablature. You may even see specific chord diagrams shown on fretboard diagrams above the stave. The notation that accompanies the video below is a good example of this.

The Nashville Numbers System

This system was developed to allow musicians to change the key of a song quickly without having to rewrite a chord chart. It defines the scale position of the chords in a song’s harmonic progression using numbers instead of specific pitches. Each of the seven chords in the harmonized major scale receives a number to represent their scale position within the scale. For example, the harmonized C major scale would be represented this way:

C Dmi Emi F G Ami Bdim C

1 2mi 3mi 4 5 6mi 7dim 1

The Importance of Reading Music

Reading music allows us to play a composition exactly as the composer intended. A good reader then learns how to interpret the notation and add their own expressiveness to a piece.

Specifically, reading notation allows us to analyze a piece of music for a better understanding of the chord/scale relationship, as well as the phrasing, motifs and dynamic markings.

Tablature gives us the best of both worlds. It combines standard rhythm notation with fretboard locations — something we may understand better than recognizing a note on the stave and making that connection to the fretboard.

The Video

My Trading Licks video jam sessions illustrate how we can create, document and share music via notation and tablature. In this series of videos, I play a two-bar phrase, and you can then jam along with me in the spaces I’ve left for you to respond with your own phrases. In the video above, you’ll be playing over D7(#9), E7(#9) and A7(#9) chords. Either the D blues scale or the D minor pentatonic scale will work perfectly over all three chords.

Click here to view and download the notation and tablature so you can learn my licks and/or analyze why the notes are working so well over each of the chords. As mentioned previously, chord diagrams are placed above the notation so you can play rhythm behind my licks until it’s your turn to solo.

The Guitar

The stunning Yamaha SA2200 semi-hollowbody electric guitar I’m playing in this video covers just about any style of music you can throw at it. Its laminated sycamore top, back and sides contribute significantly to the woody tones, and I love the highly figured glow of the sunburst finish.

The SA2200’s Alnico V humbucking pickups can also be coil-tapped for a single-coil tone, giving the discerning player six onboard pickup tones via a three-way switch, along with the push/pull taps on each tone control.

The Wrap-Up

We can use our ears to learn how to play the guitar, and watch videos to see how certain techniques are achieved. But when it comes to understanding the intricacies of a composition or documenting and sharing our ideas, nothing beats the ability to read and write music on the stave. And it’s not just guitar players that use the treble clef. Pianists, as well as mandolin, violin, flute, saxophone, clarinet and oboe players all read and share their music via the same clef.

The bottom line is this: Knowledge is powerful, communication is king, and removing any barriers to understanding the language allows the conversation between musicians to flow freely.