A Guitarists’s Guide to Chord Substitutions, Part 2: Beyond Diatonic

Secondary dominants, modal interchange and tritone subs.

As we discussed in Part 1 of this two-part series, chord substitutions are an effective way to spice up your harmonic progressions. As a bonus, they also help improve your songwriting chops and overall guitar-playing skills.

We can expand beyond the seven diatonic chords and the substitutions described in Part 1 by employing three additional techniques: secondary dominants, modal interchange and tritone subs. Let’s explore each of these in detail.

(Note: For the purposes of this posting, we’ll work in the very popular and guitar-friendly key of A major.)

The A Major Scale

Let’s start by mapping out the seventh chords that result from harmonizing the seven tones in the A major scale (A–B–C#–D–E–F#–G#):

I II III IV V VI VII

Ama7 Bmi7 C#mi7 Dma7 E7 F#mi7 G#mi7(♭5)

Now we can begin expanding upon their basic functions.

1. Secondary Dominants

Secondary dominant functions were often employed by a very famous British band from Liverpool called The Beatles. Anyone familiar with this groundbreaking group’s music knows that the harmonic structures employed in their songs were extremely interesting.

Let’s start by understanding what a secondary dominant chord is. Each of the first six chords of any major scale can be preceded by its dominant seventh chord in a chord progression.

For example:

Diatonic Chords

Secondary Dominant Temporary “One”

E7 Ama7

F#7 Bmi7

G#7 C#mi7

A7 Dma7

B7 E7

C#7 F#mi7

Each of the six diatonic chords is now functioning as a temporary “one” chord within the key. The idea here is to strengthen the sound of the pull towards the following chord. In each of these substitutions, you’ll notice that the pull towards the resolution is extremely strong when preceded by its dominant seventh chord. (The reason we don’t precede the VII [mi7♭5] with its dominant seventh is that the mi7(♭5) chord is considered too dissonant to function even temporarily as a “one” chord resolution.)

Secondary dominants are a great way to take your harmonic progressions outside the same scale without leaving the key permanently. Think of them as harmonic enhancements with strong resolutions within the context of a musical progression. Also, consider that the notes that make up the dominant seventh chords can be used in any top-line melody.

Here’s a simple musical example that demonstrates the use of secondary dominant chord subs (shown in bold):

I III VI II V I V/VI VI II V I

Ama7 / C#mi7 / F#m7 / Bmi7 Esus4 E / Ama7 / C#7 / F#mi7 / Bmi7 Esus4 E / Ama7

III7

The C#7 chord would normally be a C#mi7 chord in the key of A major, but now we have a major third instead of a minor third within the chord: the note E# (F). The E# can now be used in our melodies over this chord.

Note that you shouldn’t use secondary dominants on every chord or you’ll lose the effect. Choose one or two chords within a progression to add that delicious Beatle-like harmonic approach.

2. Modal Interchange

Modal interchange is the usage of chords from a parallel major and minor key to create a musical progression — for example, mixing chords built from the A major scale with those from the A natural minor scale. (Often composers will use the harmonic and melodic minor scale harmony too, but let’s keep things simple for now.)

Again, the A major scale consists of the notes A–B–C#–D–E–F#–G#–A, so the chords are:

I II III IV V VI VII

Ama7 Bmi7 C#mi7 Dma7 E7 F#mi7 G#mi7(♭5)

The A natural minor scale consists of the notes A–B–C–D–E–F–G–A, so the chords are:

I II III IV V VI VII

Ami7 Bmi7(♭5) Cma7 Dmi7 Emi7 Fma7 G7

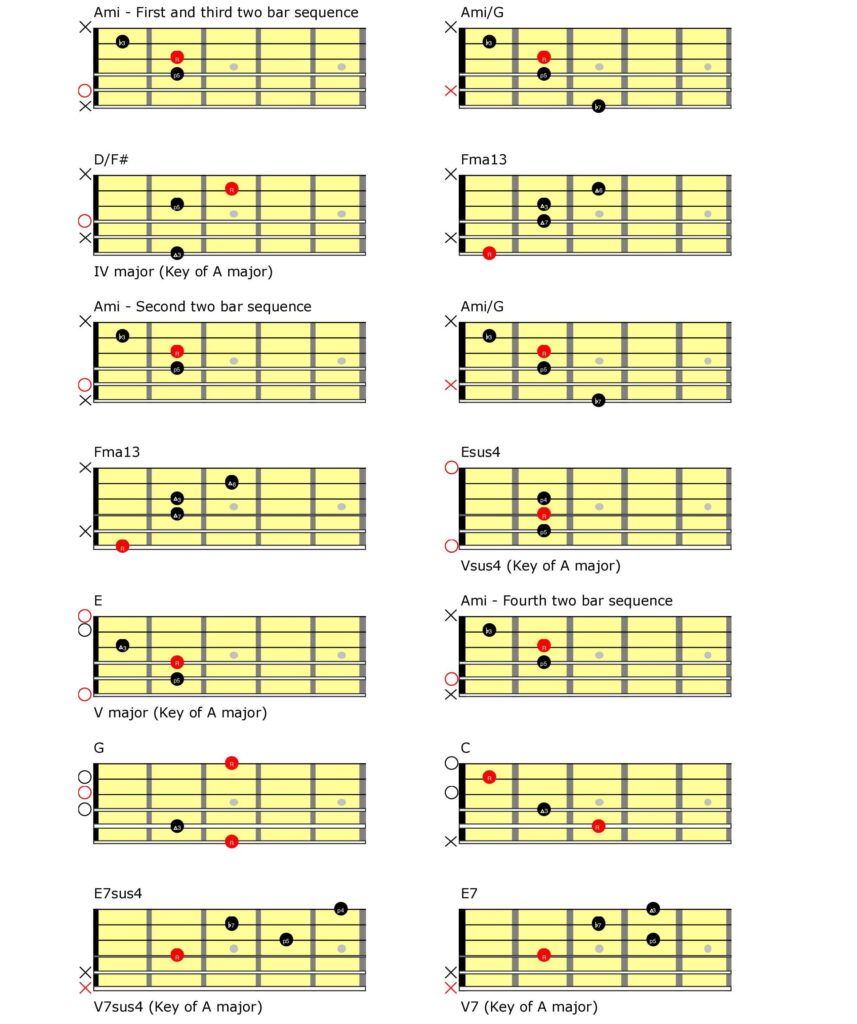

The classic George Harrison song “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” is the perfect example of how modal interchange works.

Here’s the verse in the key of A minor, with the modal interchange chord subs shown in bold:

I I/♭7 IVma ♭VI I I/♭7 ♭VI Vma

Ami Ami/G / D/F# Fma6 / Ami Ami/G / Fma6 Esus4 E

I I/♭7 IVma ♭VI I ♭7 ♭III V

Ami Ami/G / D/F# Fma6 / Ami G / C E7sus4 E7

Notice that the bolded D/F#, Esus4 and E are “borrowed” from the harmonized A major scale.

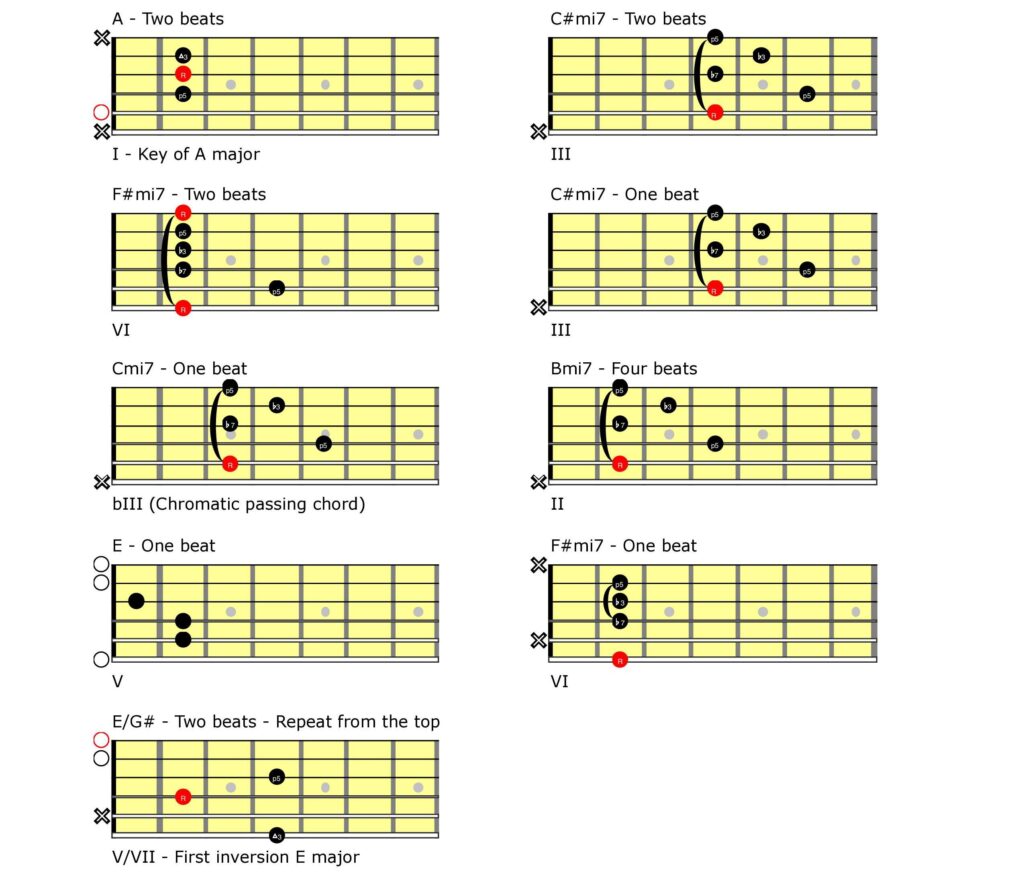

The chorus modulates directly from the key of Ami to the parallel major key of A major in a modal interchange:

I III VI III ♭III II V VI V/VII

A C#mi7 / F#mi7 C#mi7 Cmi7 / Bmi7 / E F#mi7 E/G#

I III VI III ♭III II V VI V/VII

A C#mi7 / F#mi7 C#mi7 Cmi7 / Bmi7 / E F#mi7 E/G#

All the chords in the chorus are taken from the A major scale, with the exception of the passing chromatic Cmi7 chord between C#mi7 and Bmi7.

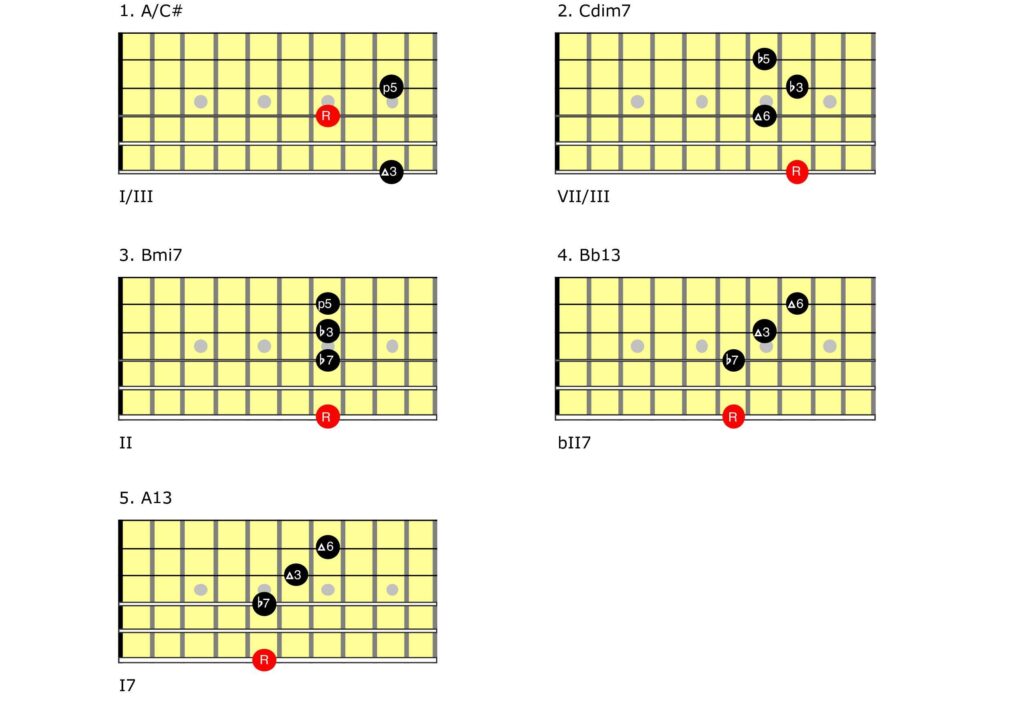

3. Tritone Substitutions

Tritone substitutions, sometimes known as flat 5 (♭5) or flat II7 (♭7) subs, substitute the diatonic dominant seventh chord with a dominant chord built with a root note a flat fifth interval above the root.

For example, a very typical chord progression in jazz is II – V – I. To give this progression more harmonic variance in the key of A major, simply substitute the E7 chord with a B♭7 chord, as follows:

II V7 I

Bmi7 E7 Ama7

II ♭II7 I

Bmi7 B♭7 Ama7

The E7 chord contains the notes E, G#, B and D, while the B♭7 chord contains the notes B♭, D, F and A♭.

Not only does this wonderful substitution allow for a descending chromatic bassline from the Bmi7 chord down to the Ama7, but each of the tones in the B♭7 chord is a semitone away from each of the tones in the Ama7 chord, making its resolution to the Ama7 chord twice as strong as the original dominant E7 chord, with only two semitone resolutions: D to C#, and G# to A.

As shown below, you can also try using a B♭13 instead of a basic B♭7 chord. I think you’ll like the tritone substitution and progression even more.

II V7 I I II bII7 I I

Bmi7 / E7 / Ama7 / Ama7 / Bmi7 / B♭13 / Ama7 / Ama7

You may also want to try using the ♭II when descending to a dominant seventh within the context of a blues chord progression, like this:

Finally, here is a really nice blues intro that could also be used for a turnaround or ending. This approach creates a descending chromatic movement towards the I7 resolution chord (A13).

I/III VII/III II ♭II7 I7

A/C# Cdim7 Bmi7 B♭13 A13

The Video

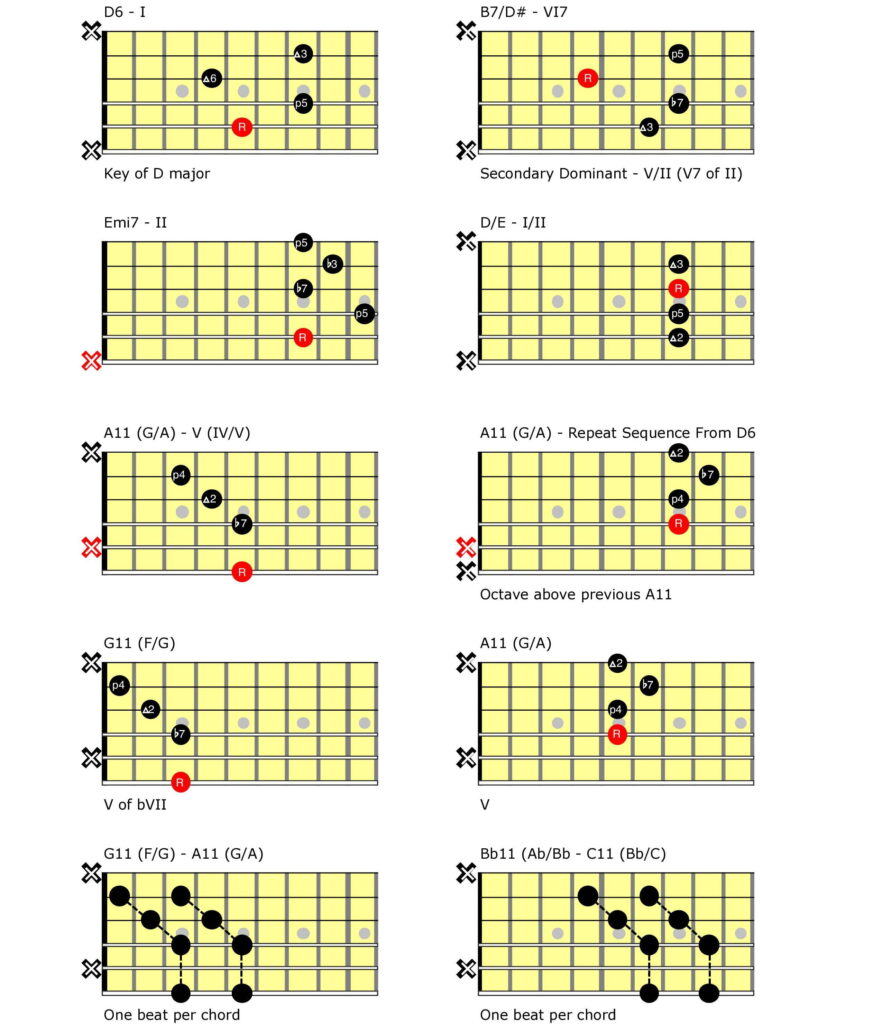

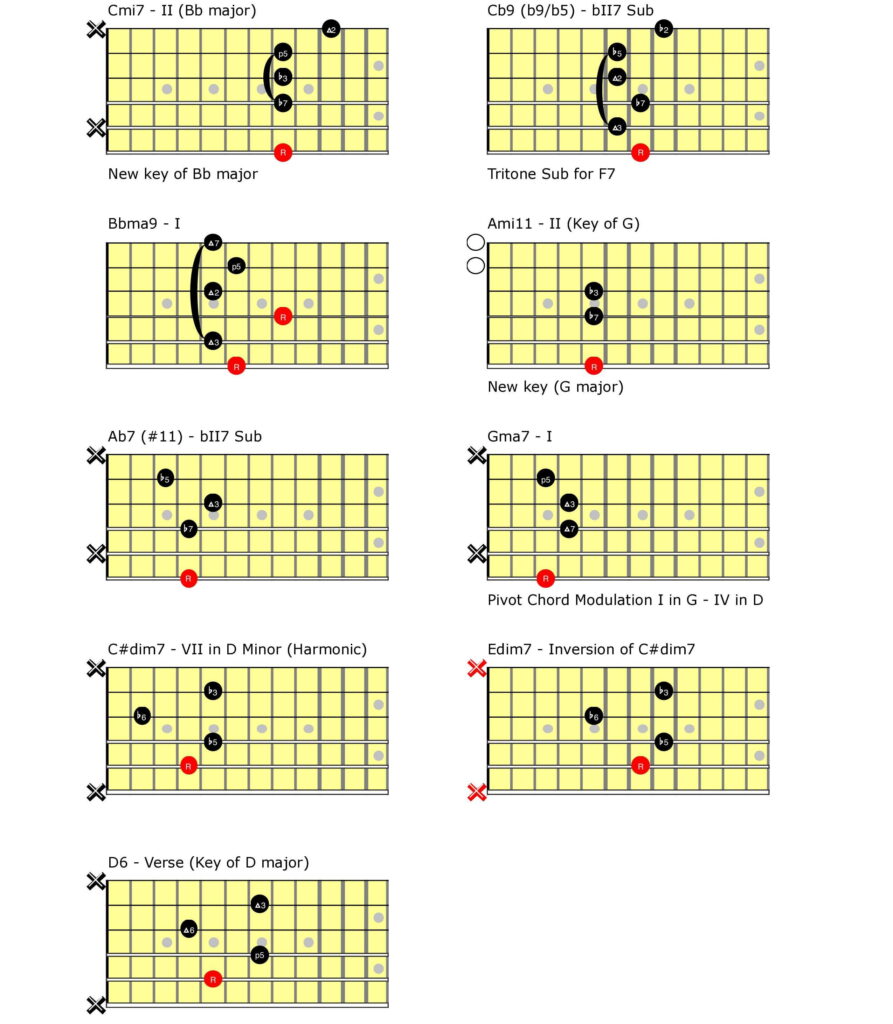

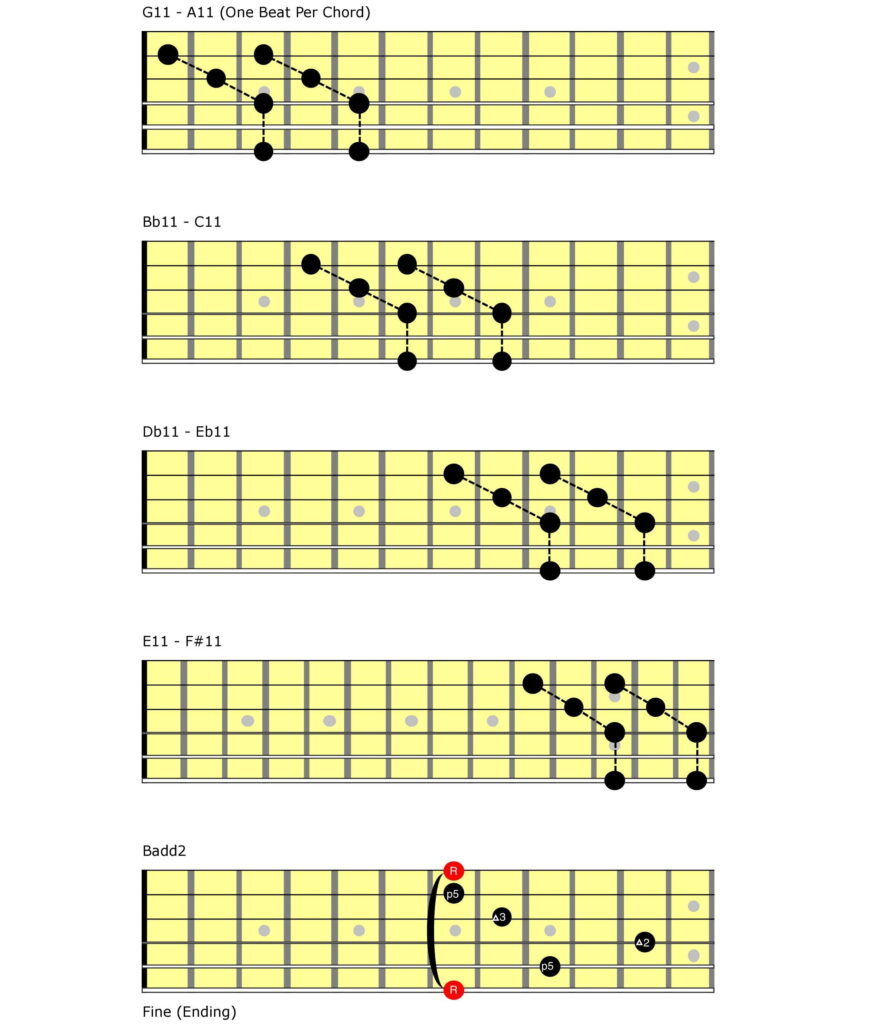

The chord progression in this video is not purely diatonic in nature. In fact, it’s quite complex, and employs all three of the chord substitution ideas detailed here. I’ve written the progression analysis below the diagrams for both sections of the demo.

Check out the chord diagrams below to see what’s happening … and follow along with the video if you can. You can also download the tabulature and notation here; this shows how I’ve outlined a lot of the chord substitutions with arpeggios instead of scales.

A Section

B Section

Notice that I’m using the instrument’s Gotoh two-point tremolo quite a bit to add shimmers to those complex chords, and the Gotoh locking tuners keep all six strings nicely in tune throughout the performance.

Ending Chords

The Guitar

Yamaha Pacifica Standard Plus guitars like the one I’m playing in the video feature two crystal-clear-sounding Reflectone single-coil pickups and a coil-tappable humbucker, developed in a collaboration between Yamaha and renowned audio manufacturer Rupert Neve Designs. As a result, chordal parts sound detailed, smooth and full of unique character, while single-note lines sing out with defined touch sensitivity. The alder body contours, neck joint and subtle chambering (crafted with proprietary Acoustic Design Technology) also allow for extra sustain and harmonic overtones.

In addition, the comfortable C-shaped satin-finished maple neck and rosewood fingerboard make transitions along the entire fretboard effortless. (A maple fretboard model is also available.)

I also love the Ash Pink color on this model, a very nice addition to the Yamaha color palette.

The Wrap-Up

When you consider the number of possible chord progressions that you could write using the seven diatonic chords, and then add into the mix chord substitutions, inversions and extensions, it’s positively mind-blowing!

If you further expand your chordal universe by interchanging (borrowing) chords from a parallel minor or major key, precede some of those chords with a secondary dominant, and descend to a resolution point using tritone substitutions, you have a galaxy of options with which to write a melody or navigate an improvisation.

I encourage you to explore, create and enjoy these new harmonic ideas, with the knowledge that continued experimentation often rewards us with extremely musical results.

PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR.

Check out Robbie’s other postings.