Tagged Under:

Case Study: Use Personal Values to Juggle a Heavy Workload

See how one music educator has mastered the art of juggling a heavy workload — what he calls “high-stakes teaching and high-payoff teaching.”

Most music educators are adept at managing a heavy workload, but Michael Gamon, chair of the department of fine and creative arts at Harrisburg Academy in Wormleysburg, Pennsylvania, has mastered the art of juggling.

He teaches 37 different classes per week. And with 350 students enrolled in the International Baccalaureate (IB) World School that spans junior kindergarten to 12th grade, Gamon teaches every student up to 8th grade and directs all instrumental ensembles plus the theater program at the high school. In addition, Gamon has a viola studio with four students at Kutztown University and performs locally himself. With so many classes to prep, activities to balance, as well as his family — his wife, who plays viola professionally, and four children — Gamon has created his own unique solution in order to stay organized and motivated.

“There are some categories of things that I need every day in order to be successful, and these things help me manage my time,” he says. “For example, I have to do something creative every day. … I’ve [also] learned that I love solving problems. Each day, if I haven’t solved a problem, I feel like I didn’t accomplish anything tangible, and I can’t rest. I also need to laugh and smile with somebody. … And I need to connect with my family in some way, even if it’s a phone call on a long day when I [won’t] get home until after they’ve gone to bed. … These things help me put my challenges into perspective.”

A New Type of Chunking

At the early childhood level, Gamon teaches the Suzuki Method. The program had existed since 2002 at Harrisburg, although Gamon began at the academy in 2012.

In 2019, violin education extended to 1st through 5th graders for one day per week. “There was enough buy-in for the [violin] program that we really needed to expand it to the lower school grades,” Gamon says.

However, Gamon noticed in the program’s first year that the elementary students and parents were not enthusiastic. In addition, he worried about the pandemic’s effect on students’ desire and ability to play an instrument. Last but not least, Gamon needed a fresh approach for his own sake. He had previously been using a conservatory prep approach that combined individual student lessons, small group sessions and large group rehearsal.

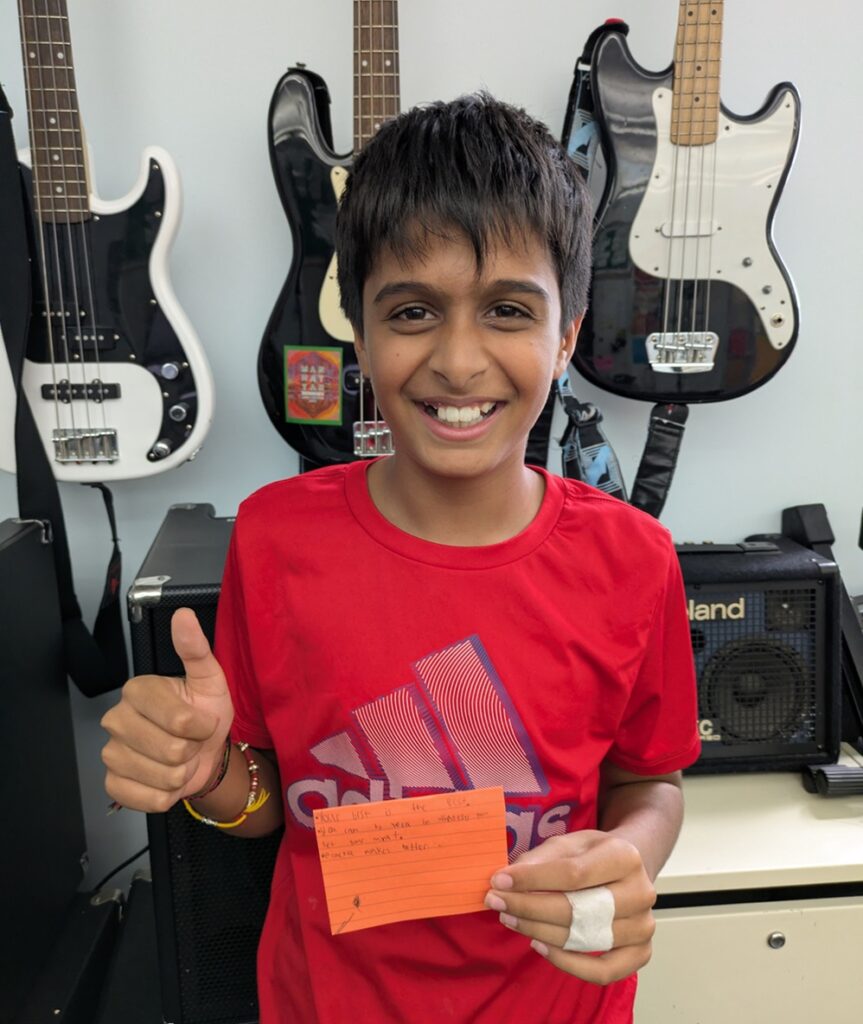

As a result, Gamon created an innovative role-playing game (RPG) that uses goals in the violin curriculum and overall grade units to unlock puzzles that advance the story. Called “Novice to Ninja” (read “Portal to Another World: A Role-Playing Game Enhances Beginning Violin Lessons”), the RPG “came out of the reality that I needed to be able to chunk my curriculum and differentiate it at the same time,” Gamon says. “There was no way that I could prep for 30 classes to be 30 distinct classes. … The RPG allowed me to create a framework through a story and an adventure that I can teach through six separate grades [including kindergarten] and have them move through the story together each week. But I can differentiate for each of the students and each of the classes. … If I had to come up with separate back-to-back-to-back lessons, I wouldn’t be able to teach anything about violin.”

As a result, Gamon created an innovative role-playing game (RPG) that uses goals in the violin curriculum and overall grade units to unlock puzzles that advance the story. Called “Novice to Ninja” (read “Portal to Another World: A Role-Playing Game Enhances Beginning Violin Lessons”), the RPG “came out of the reality that I needed to be able to chunk my curriculum and differentiate it at the same time,” Gamon says. “There was no way that I could prep for 30 classes to be 30 distinct classes. … The RPG allowed me to create a framework through a story and an adventure that I can teach through six separate grades [including kindergarten] and have them move through the story together each week. But I can differentiate for each of the students and each of the classes. … If I had to come up with separate back-to-back-to-back lessons, I wouldn’t be able to teach anything about violin.”

The RPG not only reignited students’ enthusiasm for learning violin but also fulfilled several of Gamon’s own needs as a person and a teacher. “We really needed a way to create adventure, excitement, interest and escapism for students who were handling the stress of the environment [being in pods] in the same space all day… and the larger stress of being in the middle of a pandemic.I love teaching violin, but if enough of the students and parents were no longer interested in violin, I’d lose the whole program, and I wouldn’t get to teach what I love. … ‘Novice to Ninja’ came out of that stressful situation and showcased how to solve a problem by being creative.”

Previously, Gamon had tried checklists and spreadsheets to manage his priorities. However, he found the approach didn’t work for him. “As a musician, whenever I got to the end of the list, I would feel anxious because part of what gives a musician stability is knowing that there’s a project coming. … Some of those more traditional ways of managing time aren’t effective for an artist, a creative person, a freelancer or a teacher. … The spreadsheets, lists and very careful task management are all tools to help solve problems, but they’re not the solution in themselves.”

Perspective and Fun

The “Novice to Ninja” RPG also fits in well in an IB school, which teaches students and staff to examine a process from the research phase through to development and further ways to improve. “I’ve learned that perspective and fun are tied together,” Gamon says. “Thinking through the perspective of the student as well as my perspective as the teacher and then moving back to the big picture perspective and the goals of the school and the community injected the fun in teaching for me. It hasn’t been [as] stressful or as overwhelming as I thought it might be, and it helped me as a person to enjoy what I’m doing.”

The interest in the RPG has spread throughout the entire school. “It’s definitely changing the lives of the students,” Gamon says. “For the first time since I’ve taught at Harrisburg, high school seniors are really interested in what’s happening in kindergarten.”

In fact, the middle school’s Dungeons & Dragons club is now in on the action. “I have some students who have risen to the rank of co-authors. They are writing additional articles and stories and campaigns for the RPG.”

In addition, 3rd graders have been building dioramas in Minecraft and Fortnite. “They’re adding to the story, too … and I can link and connect to that,” Gamon says. “This inspires students to understand that it’s more than violin.”

Though Gamon has never played Dungeons & Dragons, he says that he loves fantasy, storytelling, logic systems and game theory. “Gamifying music is tricky to do,” he says. “Now that I’m on the vanguard of people who are doing it, I started to lean into my own naivete, which allowed me to not get too sentimental whenever [students] want to change something. It’s easy as a creator to feel that it’s all yours. But it should be theirs, not mine. This is their world. They need to be looking at ways to engage in it and ways to leave their mark. And that’s true for music, too.”

High Stakes and High Payoff

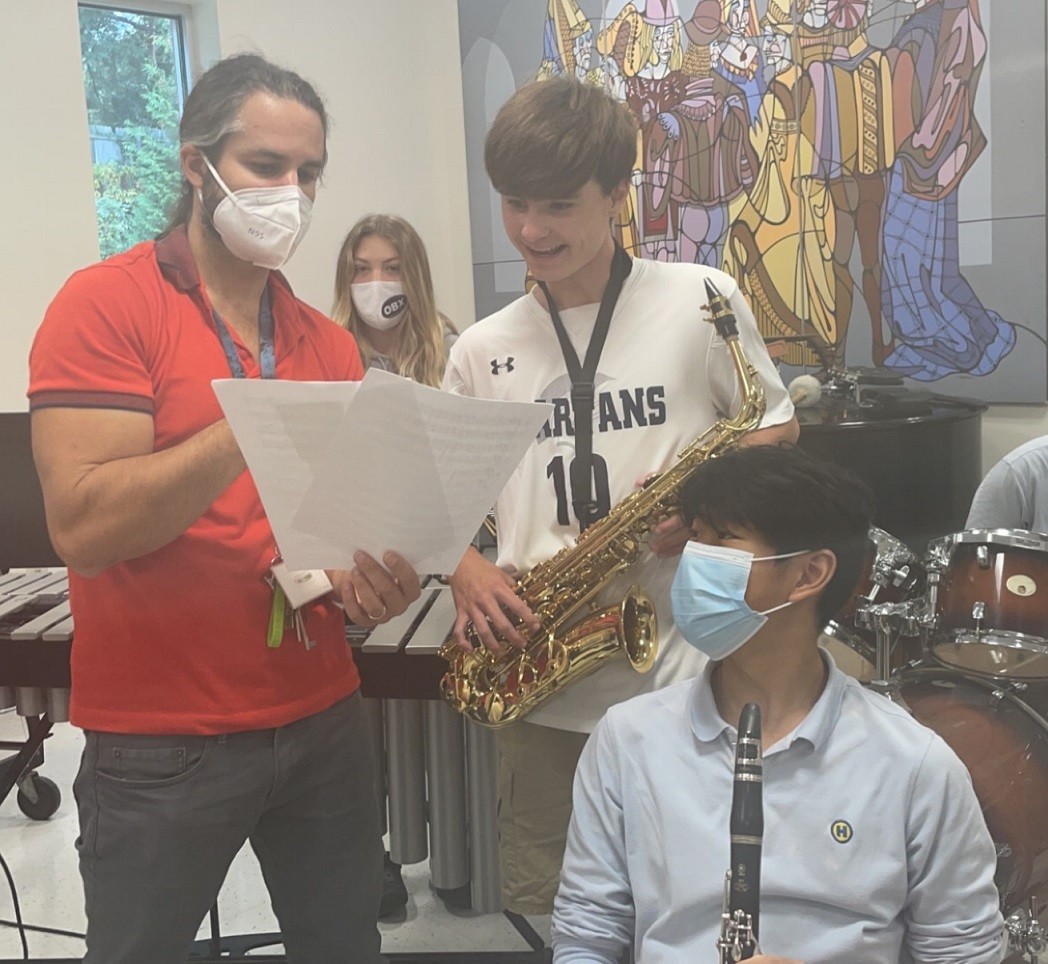

Starting in 5th grade, Harrisburg students can choose a new instrument in strings, winds or brass. At the middle school, Gamon conducts the symphonic orchestra.

Starting in 5th grade, Harrisburg students can choose a new instrument in strings, winds or brass. At the middle school, Gamon conducts the symphonic orchestra.

In high school, most students are involved in music to some capacity. About 20 students at a time choose to participate in The Center for Creative Arts, one of five in-school programs that high schoolers must join. Within the centers, students work on individual non-graded quarterly projects that have some sort of service component — for example, to learn piano and play for a morning meeting or to put together a band for a community holiday concert. The centers “help encourage lifelong learning and experiential learning,” Gamon says. “As a prep school that’s very academic and rigorous, creating a space for students to learn for their own sake and learn for their own passion are skills that we must teach our students. … [As center director, my] job is to help students stay on task and on target and build a plan and follow through with that plan.”

Gamon also teaches the two-year IB diploma program music course in which students must put on the hats of a researcher, creator and performer. Students analyze a type of musical piece, composer or genre, then they create and perform a program. The class, therefore, is very individualized while following a framework. Their work is evaluated by an IB panel.

Furthermore, Gamon teaches Stagecraft and directs the school’s spring musical, which rehearses from September to March. In Stagecraft, students learn about lighting, sounds, props, costumes, construction building, design and marketing.

Furthermore, Gamon teaches Stagecraft and directs the school’s spring musical, which rehearses from September to March. In Stagecraft, students learn about lighting, sounds, props, costumes, construction building, design and marketing.

Every grade has two concerts that may combine differently. In the winter, Gamon has put on a full holiday concert with kindergarten to 12th grade. “It’s a huge concert that’s a big community affair,” he says. The spring concert is more flexible with various grades performing together or separately, depending on what happens in the classroom.

Gamon, who was recognized as a 2021 Yamaha “40 Under 40” music educator, says that teaching students from preschool to college and interacting with the families at two private institutions results in “high-stakes teaching and … high-payoff teaching.”

“The parents and the students are really invested in the programs and are interested in growing and building an active community,” he adds.

In the end, Gamon understands the need to be efficient and has figured out the best ways to achieve his own maximum potential. “I have had so many opportunities to fail and succeed at [time management] because I’m so busy,” he says. “I feel like I’ve learned a couple of things along the way and continue to learn every single day.”