Tagged Under:

Jazz Chord Voicings, Part 1

Exploring sophisticated harmonies and voicings.

Studying jazz harmony and voicings is essential when you want to play sophisticated pop tunes, show tunes and standards (the pop tunes from the ’30s through the ’50s). It’s also used a lot in neo-soul and R&B … and, of course, in jazz!

In this three-part series, we’ll take you through these voicings in a progressive fashion. In this installment, we’ll talk about techniques that work well for solo piano and accompanying vocalists.

What Makes A Voicing Jazzy?

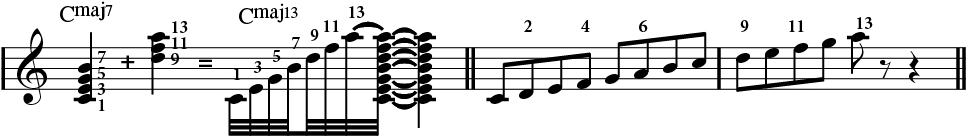

The attribute that most makes your playing sound jazzy is the use of more color tones in your harmony and voicings. Color tones are notes added to extend a chord beyond a 7th chord. Chords are built by stacking notes up in thirds (by either three or four half-steps), and when you extend a chord beyond a 7th you’ll get the following:

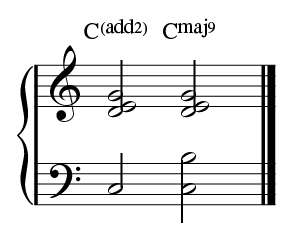

Since the octave comes after (i.e., is higher than) the 7th, these color tones are the same as other lower scale tones, but they are named seven numbers higher. So the 9th is the same as the 2nd, the 11th is the same as the 4th, and the 13th is the same as the 6th. As a rule, if a chord already has a 7th in it, the higher number is used in naming; if it doesn’t have the 7th, the lower number is used.

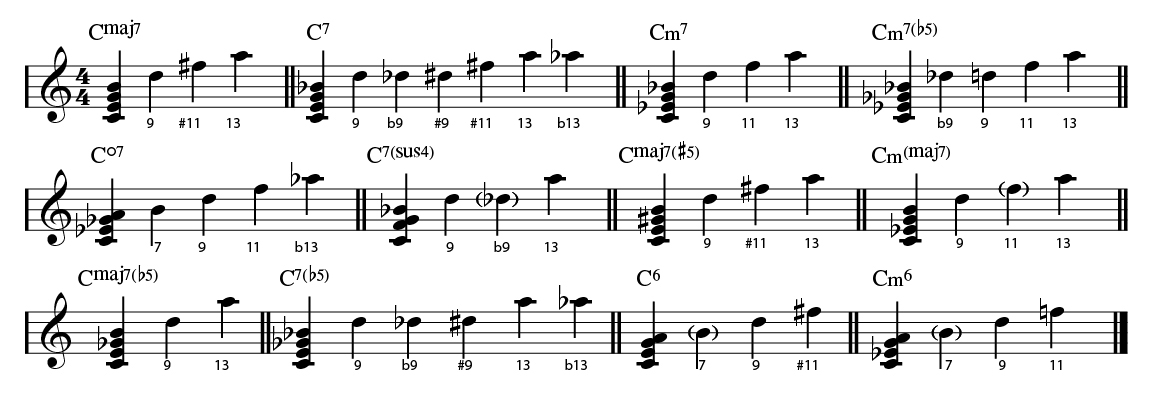

Not every scale tone can be stacked up to make advanced chords — for each chord quality there are good notes and not-so-good notes, because they are too dissonant, or harsh to our ears. Here are a wide variety of chord qualities and the color tones that are usually added to them:

How did those choices get made? If you refer back to our “Well-Rounded Keyboardist” column on the basics of chordal harmony, you’ll see that when scale tone chords are constructed, certain chord types occur on more than one scale tone. A Major-seventh chord, for example, occurs on the first and fourth step of the major scale, so the Cmaj7th chord that occurs on the fourth step of a scale happens in the key of G major. That key has an F-sharp in it, so when you get to the 11th it is called a “sharp-11th,” since it is raised up a half-step. This avoids the harsh clash that happens when you play both the 3rd (E) and the 11th (F) in the same voicing.

The Dominant-seventh chord always occurs on the fifth step of a scale, but when you compare the major scale and the most common minor scales/modes, you’ll find that the 9th and 13th tones will vary, like this:

That’s why, when you are using the V7 chord in a minor key, you’ll want to use a flatted 13th in order to maintain the minor key sound.

For the sake of brevity I’m not going to show the harmonic justification for all the other chords types I demonstrated earlier, but don’t think of these choices as absolutely rigid rules. When using a Dominant seventh chord in a major tonality, you can, for example, use all flavors of the 9th and the 13th tones to create small movements within your voicings.

The Important Tones

Certain notes are critical to define the chord quality — others, less so. The root is the most important, and someone in the band needs to be playing it down low. As a solo pianist you’ve got to play it, but if there’s a bass player, they will usually cover it, freeing you up to do other things. The next most important tone is the 3rd — that’s how we know if a chord is major or minor. The next critical tone is the 7th, or the 6th in the case of a sixth chord. I skipped the 5th, as it is only important if your chord has an altered 5th in it, be it an augmented chord, a major or dominant-seventh with a flatted fifth, or a minor-seventh with a flatted fifth (commonly called a half-diminished chord).

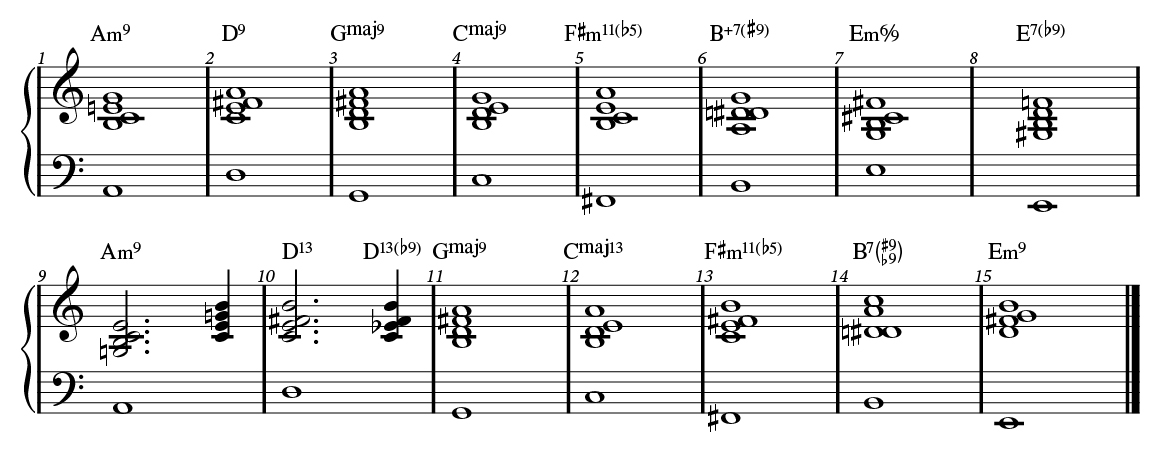

From here, you are free to start using our color tones (9th, 11th and 13th) to make your voicings more jazzy. If needed, you can leave out the 5th so you have fingers available for those color tones. Check out this example of the chords for the song “Autumn Leaves” played with 4-note right hand voicings and a single note in the left hand. This approach is a bridge between the pop/rock voicing style discussed in a previous blog and more advanced jazz treatments, and it has the benefit of freeing up the left hand to play a walking bass line if needed.

Notice that I use good voice-leading throughout, always moving to the nearest note in the next voicing. In bar 9 I jump up two inversions on the second A-minor 9th chord, so I don’t travel too low. In bars 10 and 12 I leave out the 5th so I can add the 13th as discussed earlier. On the D13 chord in bar 10 I move from the natural 9th to a flatted 9th as an inner voice movement that resolves down into the D of the following G-major 9th chord. I again leave out the 5th of the B7 altered chord in bar 14 so I can use both the flatted and sharp 9th tones at the same time, for a wonderfully dissonant/jazzy tonality.

Two-Handed Voicings

You can play richer and fuller voicings if you spread them across both hands. The most common way of doing that is to play either the root and 7th or the root and 3rd in your left hand, and then add other tones in the right hand, as demonstrated in the example below. Try not to play any doubled tones between the hands.

Here’s “Autumn Leaves” again, using this approach:

Now I’ll add some chord substitutions to make our example sound even cooler. I’m mostly using the concept of secondary dominant chords and tri-tone substitutions that I first explained in my blog about functional harmony. In the first audio clip, I play the chords by themselves, and in the second clip I play them accompanied by bass and drums so you can hear them in context.

Analyzing what I did, the E-flat ninth chord in bar 1, the D-flat augmented ninth in bar 3, and the A-flat ninth with the flatted fifth in bar 10 are all tritone substitutions of the secondary dominant chords that can be used to set up the chords that follow them. Also notice my use of the suspended fourth resolving into the third for the D dominant seventh in bar 2, and the nice color tone movement on the B dominant seventh in bar 14.

I know, it seems like a lot to digest, so spend some time reviewing — you’ll get there! Next: More jazzy chord voicings.

All audio played on a Yamaha P-515.

Check out our other Well-Rounded Keyboardist postings.

Click here for more information about Yamaha keyboard instruments.