Tagged Under:

Learn to Play the Blues on Piano and Keyboard

Explore the various forms that the blues takes.

The blues is a form of music that developed in the late 19th century as a way for African Americans to express their suffering and emotional state. It has evolved greatly over the decades and now incorporates numerous variations adopted from rock ’n’ roll, jazz, gospel and many other styles of music.

Here’s a guide to the most common forms that make up the blues universe today.

The Basic Blues

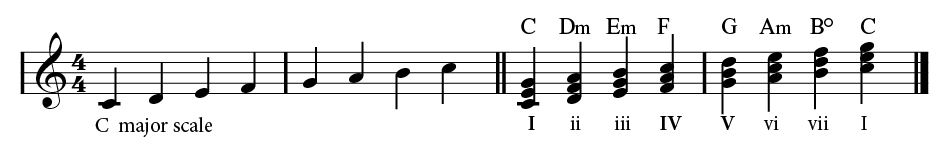

Musicians refer to the blues as being a I-IV-V progression, but what does that mean? Those roman numerals stand for the root, fourth and fifth scale tone chords that occur within any given key. For example, these are the scale tone chords in the key of C:

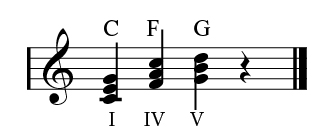

So in this key, the C, F and G chords are used to play the blues:

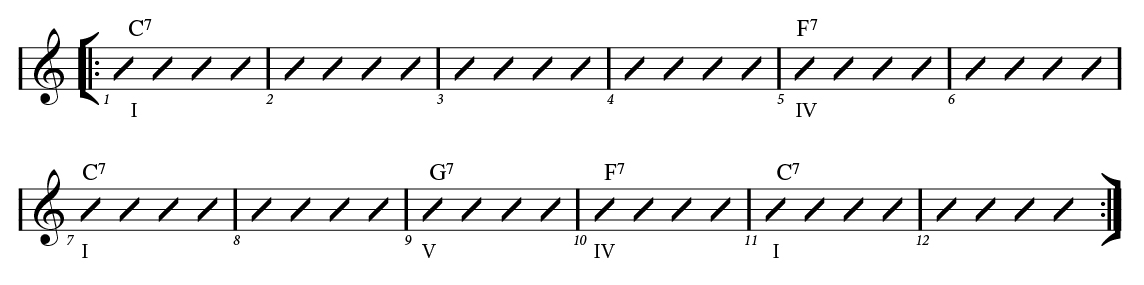

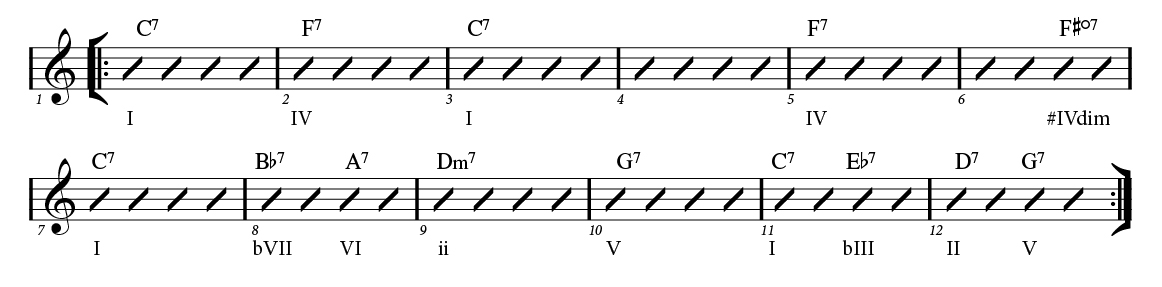

However, it’s common for all the chords in a 12-bar blues progression to be played as dominant seventh chords, where a flatted-seventh is added to each chord, as shown below.

There are many examples of famous pianists using this classic blues form. Check out this Ray Charles performance, and then compare it to this Otis Spann song performed by guitarist Albert King. Both are using the same telltale I-IV-V chord progression, and seem to point the way for how rock ‘n’ roll grew out of rhythm and blues. When played at slow tempos, the blues can evoke strong emotions, as you can hear in this recording from blues legend Pinetop Perkins.

Two Common Blues Variations

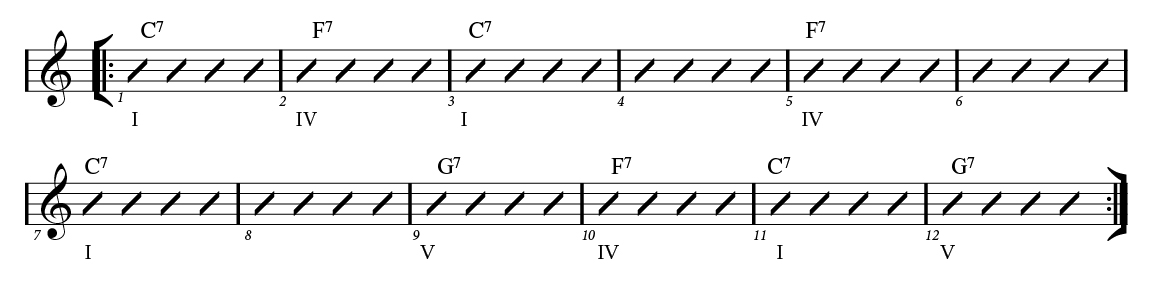

Rather than staying on the I chord for the first four bars, here’s a variation that’s often used instead. It adds a IV chord in bar 2 before going back to the I chord in bar 3:

The last bar also goes back to the V chord for what is called a turn-around, which is a way to set up the song to repeat. This variation is extremely popular and can be heard in many blues performances — for example, in this session featuring Johnnie Johnson and this wonderful Ray Charles recording.

Jazz musicians often inject a little more colorful harmony into the blues, using what some call a gospel lift. Here, the IV chord in bars 5 and 6 moves through a diminished chord on the sharp-four scale tone before coming back to the I chord in bar seven. Also, in place of the V chord going down to the IV chord in bars 9 and 10, many players like to use the jazz-centric ii-V movement. In the example below, that gets accomplished with the use of some functional harmony in bar 8, with the A7 setting up the D minor nicely, and the B-flat seventh doing so for the A7:

You can hear this approach on the classic Charlie Parker tune “Now’s The Time.”

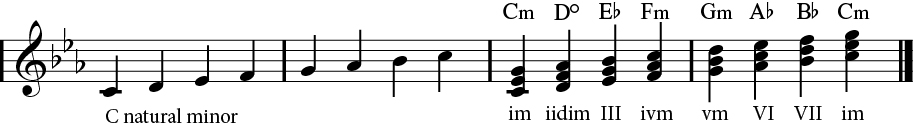

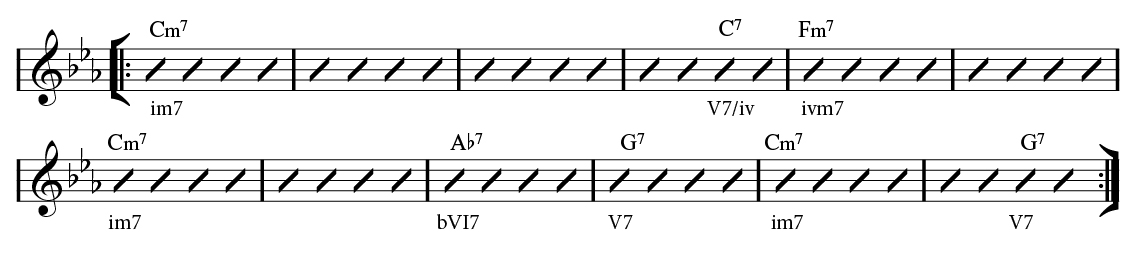

Minor Blues

For a music style often used to evoke pain and sadness, it should come as no surprise that there’s a minor blues form as well. In a natural minor scale (which uses the key signature of the major key a minor third higher, in this case E-flat), the IV and V chords both end up being minor, which doesn’t give much harmonic “pull,” as you can hear in the audio clip below.

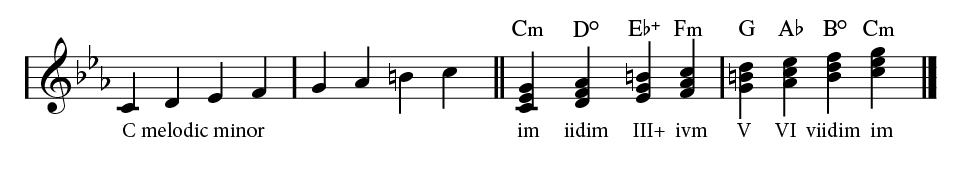

That’s why the minor blues is formed from the melodic minor scale instead. This allows the V chord to still be a dominant seventh:

The result is this common minor blues form:

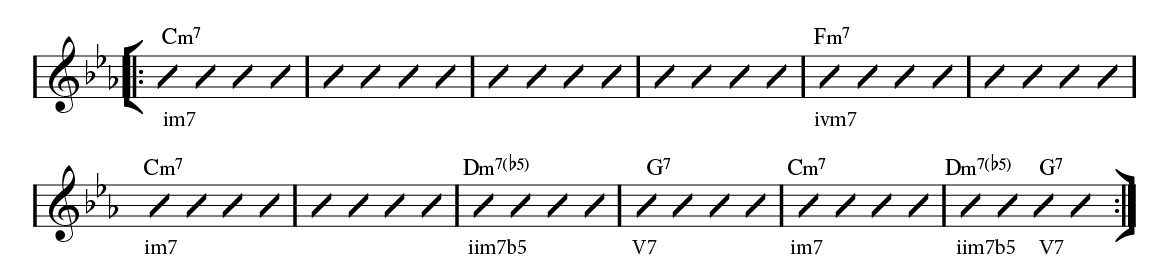

Here’s a good example of how such a chord progression can be used in a minor blues, as played by piano great Bill Evans.

A common variation substitutes a dominant seventh VI chord for the iim7♭5, so you’d play an A♭7 instead of the Dm7♭5:

This can be heard in Aretha Franklin’s performance of B.B. King’s famous “The Thrill Is Gone.”

Next month we’ll learn some keyboard licks to play over these blues forms.

All piano examples played on a Yamaha P-515

Check out our other Well-Rounded Keyboardist postings.

Click here for more information about Yamaha keyboard instruments.