Tagged Under:

Learning to Solo

How do you go about making up a piano or keyboard solo to play over a chord or a song section?

For many listeners, there is no greater thrill than when the song allows one of the musicians to step out and take a soaring solo. In fact, in jazz and blues, it is often the improvisational soloing that is the entire point of the performance, with the song merely serving as a vehicle to allow the musician to express themselves in their own unique way.

For the beginning keyboardist, it can be difficult to comprehend how to create a memorable solo over nothing more than a chord (or chord progression) and the groove provided by the rest of the band. If you’ve been wondering just that, read on …

You Need a Foundation

The best place to start is to learn what notes sound good with the chord that is being played. And the obvious first choice is the notes of the chord itself! That’s the concept that we discussed in this posting, when we started arpeggiating through chord progressions.

But many opportunities to solo on pop, rock and blues songs require you to play over a single chord for several bars (or more), so just using the root, third, fifth and seventh of a chord won’t allow you to create the types of interesting solo phrases you’ll want to play. Let’s explore two different scales so common in pop/rock music that they will give you a jump-start on sounding good right away.

The Blues Scales

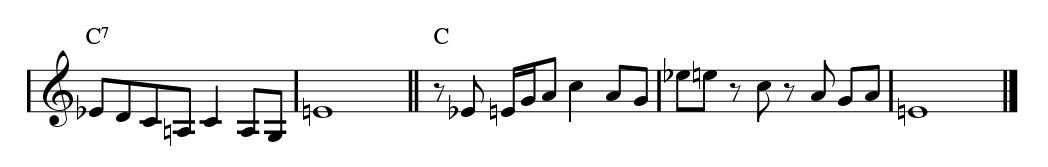

There are two versions of what are known as blues scales; becoming comfortable and proficient with them is a great place to begin learning how to solo. The first is called the Major blues scale, shown below:

This scale contains the root, third and fifth of the major and dominant seventh chords shown above the stave, along with the 2nd and 6th notes of the major scale. What makes it bluesy is the added flatted-third tone (in this case the E-flat). While these are good notes to use to craft solos from, all too often beginning players just play the scale in succession, which is alright, but not very interesting. You want to use these notes to create interesting melodies, not just run up (or down) the scale. Here are two suggestions (the audio clip starts with two bars to establish the groove):

Notice that at no time in either of these phrases do I just play the scale — in fact, I don’t even start on the root C note. I also varied my rhythms to keep the lines interesting. (The rhythm and feel of your solos can be almost more important than the note choices.)

These suggestions don’t include the flatted seventh that is an important part of the chord, despite the fact that this scale can be used on a Dominant seventh chord. Here’s a variation of the scale that adds in that important note:

Now we can craft some melodic ideas that support the full sound of the Dominant seventh chord, like this:

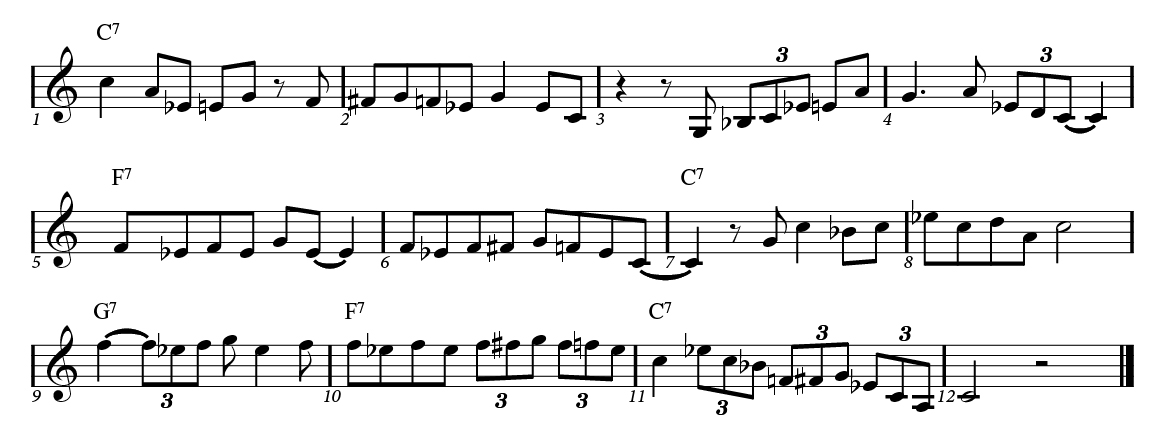

The second blues scale (shown below) is actually the most common one:

When this scale is played over a major or Dominant seventh chord, the flatted third, sharp fourth/flatted fifth and flat seventh all contribute to the tension and character of the phrases, which is what makes it sound bluesy. Notice that this scale doesn’t even include the major third. It sounds equally good on a minor seventh chord, where the flatted third fits in as expected. Here are a few licks crafted from the scale, played against both Dominant seventh and minor seventh chords:

As we did with the major blues scale, if we add the note that’s missing to help outline the Dominant seventh chord, we get an even more interesting version. Here’s what the scale looks and sounds like when we add in the major, or natural third:

Here are a few phrases using this scale variation against the Dominant seventh chord:

Blues Scales in Action

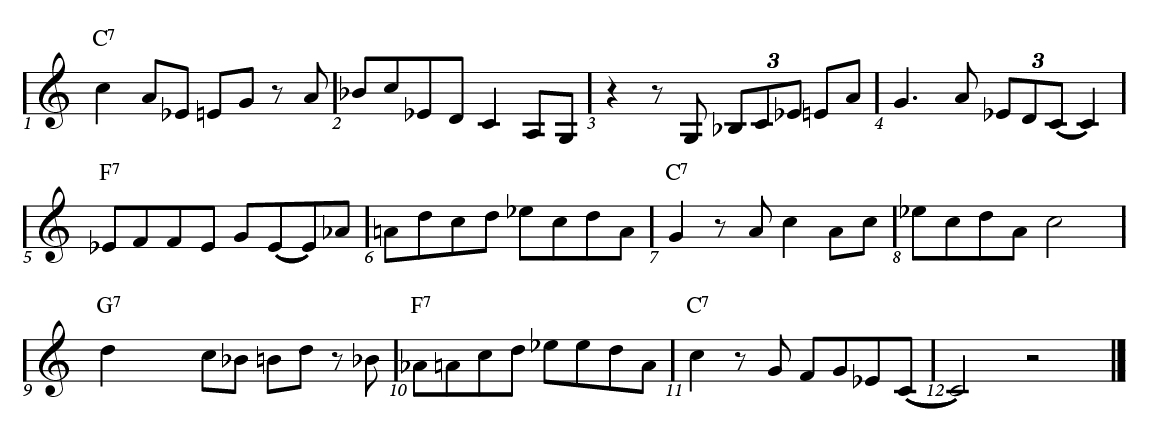

Now let’s apply these blues scales in the context of a song. The blues form is a classic song style, consisting of 12 bars that repeat, as follows:

The illustration below shows the notes of the corresponding major blues scale (with the added flatted 7) for each chord to give you a reference for the notes we are going to use.

Here are some melodic solo ideas that utilize a different scale for each chord change:

When it comes to the basic blues scale, it’s common practice to use only the scale from the key center, and to not change to the related blues scales for the other chords in the progression. In fact, many blues players just stick with the key center blues scale for their entire solo, even if the progression has more chords than the basic blues form.

That said, you can add some variety to your solo by changing your major blues scale note choices for each chord, and then occasionally just play a key center blues lick over any chord. As an example, check out this next solo, where I always use the C blues scale over the F7 and G7 chords, even though I vary between regular and major blues scale notes for the C7 chords:

All audio played on a Yamaha P-515.

Check out our other Well-Rounded Keyboardist postings.

Click here for more information about Yamaha keyboard instruments.