Tagged Under:

Playing Well With Others

Performing with a singer or as part of a band requires a very different approach.

There’s a world of difference between playing keyboards by yourself for enjoyment, and making music with other people. If you’re accompanying a singer or performing as part of a band, you’ll probably need to adapt your keyboard technique to some degree.

In this article, we’ll take a closer look at some of those adjustments.

Supporting A Vocalist

The first rule when providing accompaniment for a singer is: Don’t play the melody! That’s the job of the singer, and they need to be given the freedom to sing the melody as they see fit. You need to stay out of their way and let them do their thing.

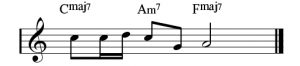

Your role is to play the chords and any musical figures that are signature parts of the song. That said, you need to know the melody line, both in terms of the notes and also where the singer is singing and when they have breaks. When the singer is singing, it’s crucial that you not play any notes that may clash with the melody, as you might cause the singer to stray off their pitch. For example, let’s say the melody is a simple one like this, sung over three chords:

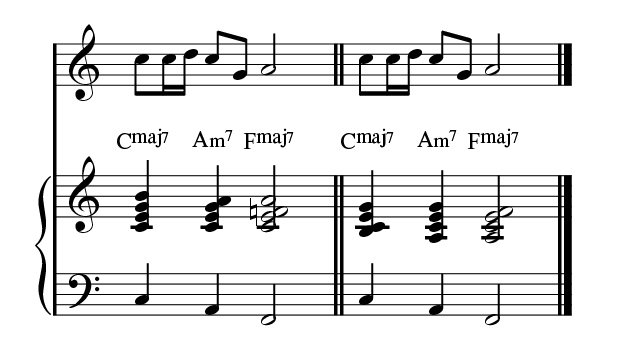

The opening note of the song has the singer singing the root of the accompaniment chord, but the chord itself is a major-seventh. If you put a B (the major-seventh note) at the top of your voicing, it is only a half-step below the note the singer is trying to sing, and so it’s likely to make them feel uncomfortable; it may even pull their pitch down a little flat. For that reason, it’s better to use a chord inversion so the major-seventh is in the middle, or at the bottom of, the voicing. Compare the two versions shown below: The first causes a clash for the vocalist, while the second is much more pleasing to the ear.

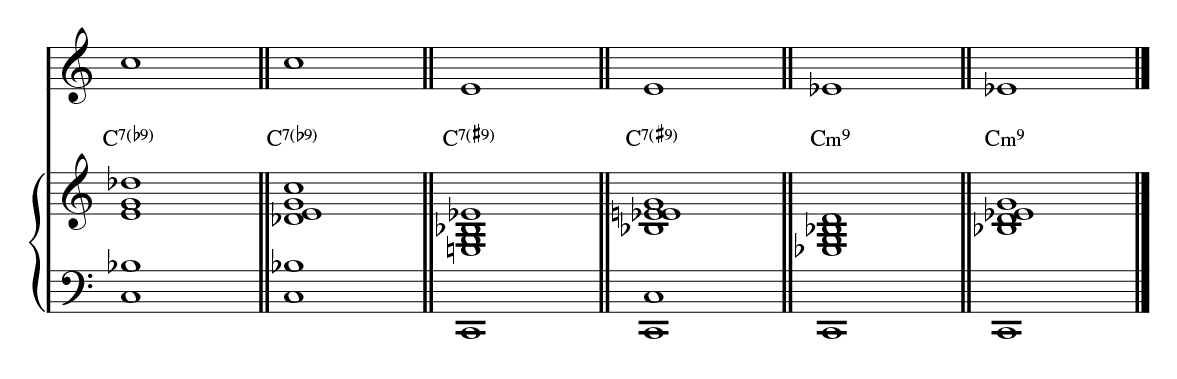

Particularly if the harmony calls for more advanced chord types, you need to avoid putting a note at the top of your voicing that’s going to negatively affect the singer — especially if the note is a half-step away from the melody. For example, if the singer is singing the root, don’t put a flat-ninth at the top of your voicing; if they’re singing the major third, don’t put a sharp-ninth at top; if they’re singing the minor third on a minor ninth chord, don’t put the ninth at top. Here are the wrong ways, followed by the right ways, to voice chords in these situations:

The last consideration when working with a singer is to not play too busily when they are singing the melody line. Avoid fancy figures and runs that will either get in the way of the melody or draw attention away from the singer. You’re there to support them, not show off! Better to fill the space when there’s a break in the melody line, or at the end of a section. We’ll talk more about this in a future posting.

Joining the Band

If you’ve only been playing your keyboard at home by yourself, the first time you try to play with a band, you’ll quickly realize that it’s a very different situation. By yourself, you’ll instinctively want to fill out the sound, to define the bass note or the rhythmic feel of the song, etc. Once you join a band, however, you need to understand that the other players have the responsibility of doing some of those things, and you don’t want to get in their way. As when accompanying a singer, keep the word support in mind at all times. Your job is to help make the whole band sound good, not just yourself.

Getting Into the Groove

What you play wants to be in perfect time with the drummer. In general, “less is more” is the key to making that relationship work well. When I play in a band, I often concentrate on what the drummer’s playing on their hi-hat (the pair of small cymbals mounted on a stand that drummers play both with a pedal and their sticks). I find that listening and looking at the hi-hat is a good way to help me lock in with the overall rhythm.

The pattern that the drummer plays with their right foot on the kick drum is also very important to the groove of the tune, and so you want to try to match up with that too. Bear in mind that the bass player is also going to be trying to lock in with the kick drum pattern, and you don’t want to be getting in the way of them establishing a great groove. Listen to what the bassist and drummer are playing and come up with a part that works well with both of them.

The Lowdown

Speaking of the bassist, there is a cardinal rule for keyboard players: Stay out of the way “down there”! Someone accustomed to playing solo piano/keyboard commonly plays strong notes (often octaves) with the left hand to fill out the sound, perhaps even adding some bass figures to give the song a good feel and some movement. In a band, however, you don’t need to do that — in fact, you should avoid it in most situations.

Here are the notes of the open strings of a bass guitar (and acoustic bass), which sound an octave lower than they are written:

A good rule of thumb is that, if there’s a bassist in the band, anything played on the keyboard from the C below Middle C or lower is potentially going to get in the way:

The bottom line (pardon the pun) is that, if you’re going to play a single note in your left hand to support your right hand chord, don’t go too low with it. Similarly, make sure that any left-hand chord voicings are constrained to that one octave below Middle C, or things will start to get muddy.

Get Along with the Guitar

In many songs, both the keyboard and the guitar will be playing chords, so you need to get together with the guitarist and decide ahead of time on what the basic chords are. And if either of you are going to add some color tones beyond the seventh of a chord, you both need to agree on what those tones will be.

Here are two very common issues that can arise between a keyboardist and a guitarist:

– One of you wants to make a chord a suspended fourth for a few beats and then resolve it to the third. You both need to do that for it to sound good.

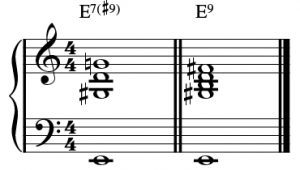

– If you are going to add a ninth to a dominant seventh chord, you both need to agree what type of ninth it will be. (Dominant seventh chords can have three different types of ninths: a natural ninth, a flat ninth or a sharp ninth.) A common real-world example of this is when a band wants to play something funky, and you play a dominant seventh sharp ninth chord on the keyboard while the guitarist is playing a natural ninth:

The clash between the two is all too obvious, as you can hear from this audio clip:

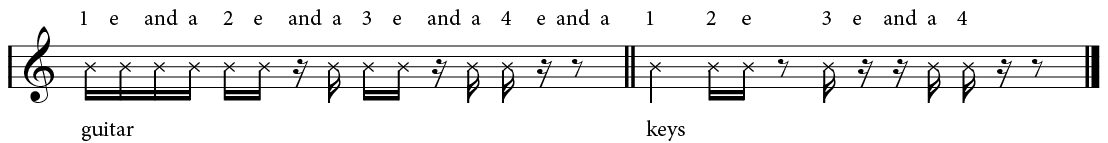

Besides getting your chords together, you and the guitarist need to come to an agreement about how you’re each going to play the chords rhythmically — at the very least, you need to listen carefully to each other’s parts. I usually let the guitar player establish the basic rhythm, and then I try to blend into their pattern. Don’t copy it exactly, though. It’s better if you only play some accents on top of their pattern.

As an example, here’s a busy guitar strumming pattern, followed by the way I might support it on keyboard, without getting too busy, and without getting in their way:

All audio played on a Yamaha P-515.

Check out our other Well-Rounded Keyboardist postings.

Click here for more information about Yamaha keyboard instruments.