Tagged Under:

What to Do When There’s No Bass Player, Part 1

How to cover keys and bass at the same time.

It’s very common for a band to include at least a singer, a drummer, a bass player, a guitar player and a keyboardist (you!). But there will be times when a gig is too low-paying to afford that many players, and often it is the bass player who is left out. The problem is that most music won’t sound right unless someone is playing those low notes and providing the rhythmic push of a good drum and bass partnership. So that role will need to be covered by you.

In this posting, I’ll provide you with some tips and suggestions for acting as surrogate bass player when a real one isn’t there, without sacrificing the all-important keyboard parts.

It’s Fundamental

My first piece of advice is to keep your left-hand bass playing very simple. For most styles of music (with the exception of swing jazz tunes and songs with specific signature bass riffs), you can’t go wrong just playing the root of the chord. With that as a starting point, you next want to come up with a rhythmic feel that matches the groove of the song, and especially one that matches what the drummer is playing on the bass drum. Listening to and locking in with that pattern will make the band sound good and support the groove with nice low notes to fill out the sound. Nothing flashy is really needed.

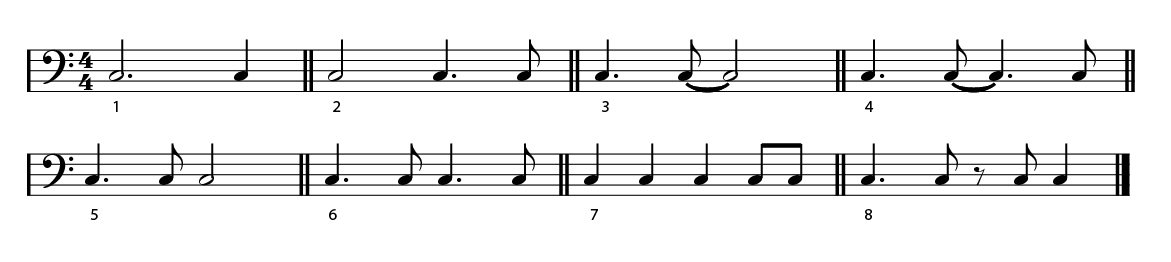

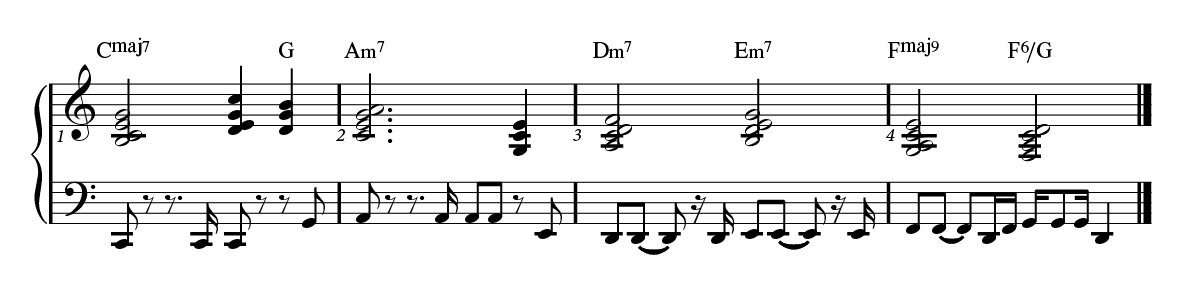

Here are some very common rhythm patterns that work in lots of songs (each pattern would be repeated many times, of course):

Note that in this audio clip (as well as the following six clips), I play each bar twice:

- Example 1 (in bar 1) is the most basic: you could just play whole notes if it were a ballad, but this adds a note on beat 4 to keep some movement going.

- Example 2 (bar 2) provides nice downbeats on beats 1 and 3, with an extra note on the and of 4 to push back into the downbeat.

- Example 3 (bar 3) pushes into beat 2, meaning it anticipates the beat.

- Example 4 (bar 4) is similar, but it adds another note on the and of 4.

- Example 5 (bar 5) is a straighter version of the pattern, where you play a note solidly on beat 3.

- Example 6 (bar 6) adds the note on the and of 4 to push back into the downbeat.

- Examples 7 and 8 (bars 7 and 8) are both common patterns heard on countless songs.

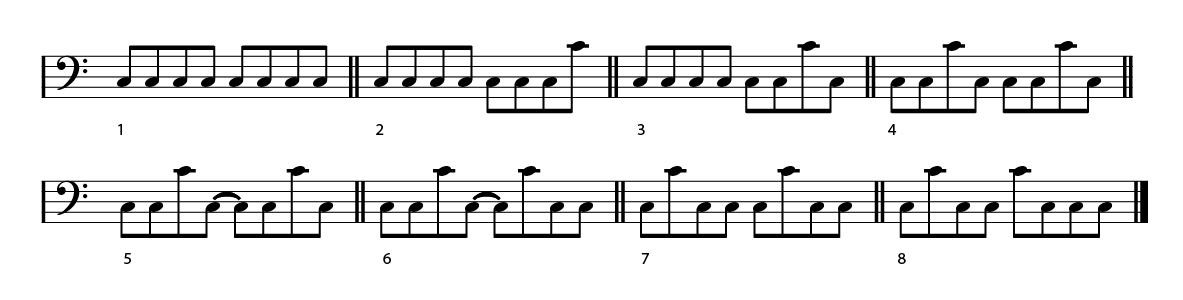

These next examples utilize a constant eighth-note feel for more driving rock and dance tunes (note that I add an upper octave at times for variety):

- Example 1 is just constant eighth notes, which always works.

- Example 2 adds a single upper octave note just before the pattern repeats on beat 1.

- Example 3 places the octave on beat 4, while example 4 places octaves on beats 2 and 4, where the drummer would often be playing snare drum hits.

- Example 5 gets a little trickier in that it anticipates into beat 3, which is a way of adjusting the pattern to match the drummer’s bass drum feel.

- Example 6 is a slight variation of where the octave occurs after beat 3.

- Examples 7 and 8 go back to steady eighth notes.

These next examples are more deeply syncopated, meaning they have more off-beats in their rhythm, and they occur on sixteenth-note subdivisions. These work well in funkier tunes:

- Example 1 gives a nice strong emphasis on the 1 and the 3 of the bar.

- Example 2 adds a note on the and of 4 to push back into the downbeat.

- Example 3 adds notes on both the 3 and the and of 3, while example 4 holds out the note on the and of 3 for the rest of the measure.

- Example 5 adds a longer note on the and of 1, and then pushes back into the top of the next measure tightly with a note on the last sixteenth of beat 4.

- Example 6 treats beat 2 with more syncopation, but then a more relaxed push back into the downbeat of the next measure.

- Example 7 is a variation of that pattern, with two off-beat hits on beat 4.

- Example 8 sounds a bit like a sequenced dance bass line or perhaps a driving Motown beat.

Adding Notes

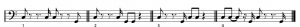

Once you’ve established a library of rhythmic figures, you can expand your note choices. Bass players often alternate between the root and the fifth of a chord, so you can introduce some fifths into your patterns like this:

Like the root-only technique, these types of lines are going to work under almost all chords, except for diminished or augmented chords. For more funky or R&B tunes, you can try these approaches:

To get more color in your lines while still keeping them simple, you can introduce other notes, but these now become more conditional on the chord quality. For example, you can add the sixth note to major and dominant-seventh chords, and you can add the flatted seventh to dominant-seventh and minor seventh chords:

Finally, here are some examples of more syncopated funky feels:

Putting It All Together

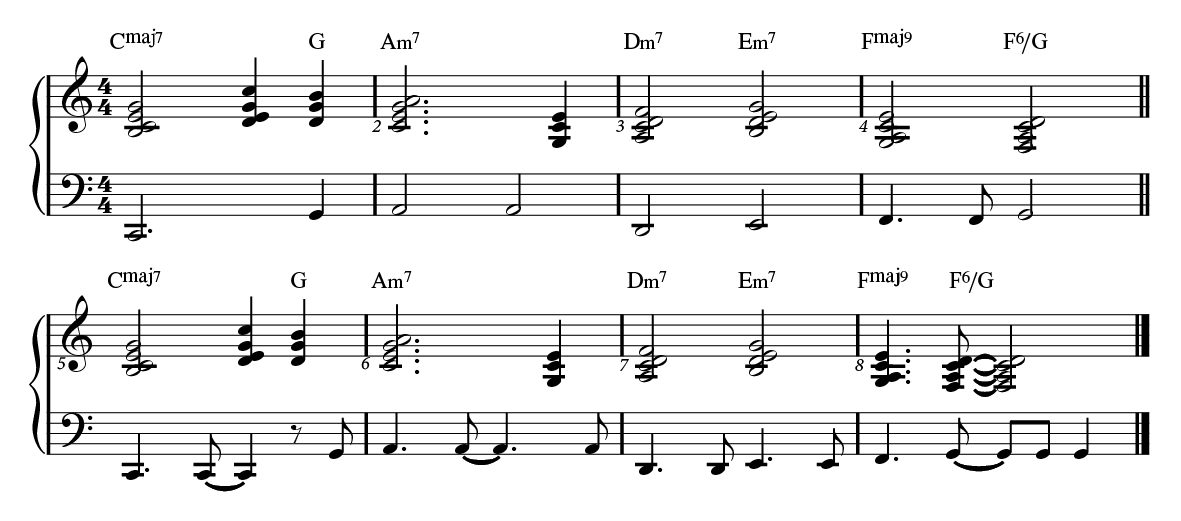

Armed with these ideas, let’s move on to playing basic songs and chord progressions. Here are two common kinds of pop ballad bass lines, using some of the ideas from the first examples:

I’m only playing root tones in the bass, but the first is very straight and open, while the second half uses more pushes into beat 3 to match the different drum feel.

This next example adds in some fifths to the bass:

Finally, let’s use some of the more syncopated figures and take more freedom with the notes:

In general, remember that it’s better to keep your left hand bass lines simple, and just support the feel of the song. You don’t have to be a flashy bass player — just keep it low and in the pocket! In Part 2, we’ll cover walking bass lines.

All piano and bass sounds played on a Yamaha P-515.

Check out our other Well-Rounded Keyboardist postings.

Click here for more information about Yamaha keyboard instruments.