Teaching Musicality to Percussionists

Try this four-step process to help percussion students communicate expressively through music.

As an educator, I have never understood why young percussionists are not taught more about musicality. My wife is a flute teacher, and she teaches musicality to kids in sixth grade. Why is it that percussionists get to college and still do not know the basics about shaping a line?

I believe there are several reasons why percussion students do not learn about musicality.

- Percussionists often do not learn a mallet instrument until high school. It is not very exciting to learn music on a toy (i.e., a bell kit). Marimbas are expensive and not readily available for students to use at home. The introduction of tabletop xylophones and portable marimbas is helping solve this issue.

- Young percussionists often do not study mallet instruments with a private teacher. This has changed over the past five to 10 years, but it is an issue in smaller schools and rural locations.

- With a variety of techniques on so many percussion instruments, instructors often do not have time to address musicality.

The list could go on and on, but these are just excuses. Music educators need to address the problem and incorporate solutions into their private and ensemble percussion teaching.

As you teach students about musicianship and musicality, remember to stress the importance of theory, history, aural skills and analysis, in combination with active listening (listening to music with focus and attention). These are the building blocks of becoming a better musician.

The approach to and interpretation of a repertoire piece, such as a concerto or sonata, that your student is playing today will be very different in five years because of the knowledge and experience he or she gains as a musician. The goal of musicality is to communicate expressively, and these steps will help you teach musicality in your studio.

Start with the Voice

Have the student put down the mallets and step back from the instrument. Then ask the student, “How are you?” To which the student responds, “I’m doing well.” Now, analyze the conversation.

Notice that when you ask a question, you end the sentence on a higher pitch than you began. When the student answers, he or she ends the sentence on a lower pitch than they began. Next, try the same exercise and ask the student to use the opposite tonal inflection or move the inflection to different parts of the sentence. HOW are you today? How ARE you today? How are YOU today? How are you TODAY? By using different inflections in the sentence, the student will begin to see multiple meanings to the same question.

Now, try the same thing with a common melody. Ask the student to sing the first line of “The Star Spangled Banner.” This works well because the first phrase outlines a major arpeggio, and the melody goes down and then up. The goal of this exercise is for students to realize that in speech and familiar melodies, we don’t speak or sing without inflection. Once this point has been established, it’s time to pick up the mallets and apply this lesson to a musical phrase.

Do Something with the Notes

Just playing the notes and dynamics is not enough. You must teach students to “do something” with the notes.

If your student’s playing sounds like the playback of a MIDI file, no musicality is present. The best way for students to tell if they are “doing something” with the music is to record them so they can immediately hear how they sound.

You don’t need a great recorder to accomplish this. Use a smartphone or laptop to record your student playing through the piece two or three times, each time using different musicality. Then review and compare the performances with the student. It is also helpful to record yourself playing the passage so your students can hear how their teacher shapes the line.

Musicality is subjective. You must teach your students how to make informed decisions. Active listening, music theory, awareness of different styles and aural skills will develop their musicality. Music theory includes knowledge of music fundamentals (elements of music notation, meter and rhythm, key signatures and scales, triads and other chords), basics of common practice harmony and analysis. Each era of music and genres within those eras have particular conventions that may not be apparent in the notation. Aural skills practice develops the inner ear; the ability to “hear” the music in one’s mind allows the student to create a conceptual performance. The student can then compare this internal performance against the actual performance to identify errors and enhance expression. These building blocks will help develop more musical percussionists.

Follow the Shape of the Line

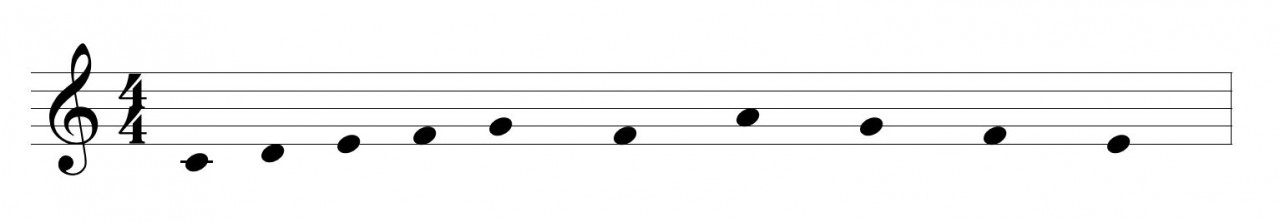

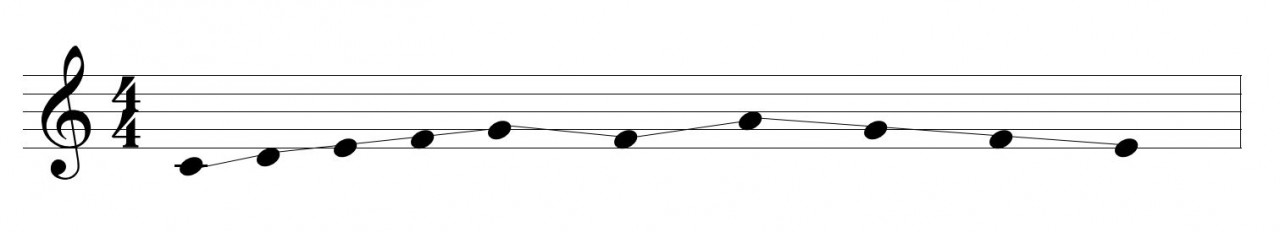

One of the basic rules of musicality is to follow the shape of the line. One concept I teach is to remove all the stems, beams, flags and barlines from the music. Only noteheads remain. You can visualize this, write the pitches on staff paper or input them into notation software if you want to be sure the student sees the result.

Next, take a pencil and connect all the noteheads:

Now play the line. Instruct the student to get a little louder as the line goes up, and to get a little softer as the line goes down.

Here comes the subjective part. How loud or soft should you get? That is a good question. It should not be a full dynamic louder or softer. A listener should be able to hear that you are getting louder or softer. Dynamics are relative. There is “room” within a dynamic to add shape. Record and play back the performance so the student can hear if he or she is shaping the line.

Practice, Practice, Practice!

Repetition is key to improving your students’ musicality. I cannot stress how important it is for students to record their performances and listen back.

Another idea is to have your students listen to recordings of the pieces they are preparing. If they are working on a violin sonata, find a couple of recordings and bring them to a lesson so you can demonstrate the different performances.

Some Final Thoughts

Do not let your students copy someone else’s musicality. Students often listen to recordings online and then imitate what they hear. This does not help them develop their own musicality! Require students to record themselves and practice playing sections of the piece with different musical approaches. (Tip: If they don’t hear a difference, have the student post the video online [e.g. YouTube, Facebook] and ask their friends for comments.)

In the beginning, do more than normal with your phrasing. Students are often shy when first learning how to shape a line. In my experience, it is easier to ask students to reign in their musicality than to get them to do more. Make sure the student understands the basic principles of performance practice. A piece of music that was written in the Baroque era is performed differently from a piece written in the Romantic era. If the students do not know the difference, assign them some listening examples. Teach your students to not be afraid to ask questions and encourage them to get feedback from their peers, teachers or mentors. As with anything, there is a learning curve.

This article only scratches the surface of teaching musicality, and I hope it gets you thinking about how to incorporate musicality into your students’ curriculum.

Students are capable of learning how to be musical at a young age, and it is our role as music educators to introduce this concept prior to high school or college.

This article was originally published in Percussive Notes, the official journal of the Percussive Arts Society (PAS).