Ask for Help and Improve Your Teaching

Expand your circle, seek specific feedback and implement advice from colleagues and mentors — with help, you can improve quicker than if you did this alone.

During my first five years of teaching, I could have benefitted from some real help. Unfortunately, I was petrified to have my high school and college band directors come out to watch my rehearsals.

My former teachers were incredibly kind and willing to help me, and they told me they would come out at a moment’s notice. But I just never felt like I had things in good enough shape for them. In hindsight, I wish I had just asked them come to my school. I don’t regret working hard on my own, but I could have saved so much time and improved more quickly if only I had set aside my fear and ego and asked for help.

The key takeaway is: You are not alone, and you don’t have to do this yourself. With a bit of initiative, you can find ways to directly improve your teaching and expand your networks outside of your once- or twice-a-year professional development conferences. The following suggestions are real situations where I forced myself to go beyond my comfort zone to grow personally and professionally.

Don’t Wait for an Invitation

The music teaching field is remarkably helpful, but it’s also hectic. If you wait for an invitation to observe or help out another program, you’ll be waiting a long time. Instead, take the lead and just reach out.

At the beginning of my career, I contacted a few well-known directors and asked if I could observe an evening rehearsal. The response was almost always a “yes” or a “yes, but would another time of year work?” Bring a notebook, jot down some thoughts and just take it all in. The next day, try something new in your classroom that you observed the night before. It might work or it might not — but it’s another tool in your bag.

At the beginning of my career, I contacted a few well-known directors and asked if I could observe an evening rehearsal. The response was almost always a “yes” or a “yes, but would another time of year work?” Bring a notebook, jot down some thoughts and just take it all in. The next day, try something new in your classroom that you observed the night before. It might work or it might not — but it’s another tool in your bag.

Observing other teachers also expands your network. I’ve made countless friends and connections by observing programs and taking the teacher out for coffee afterward to talk. These can also be social events. I’ve scheduled time with three or four friends to watch another colleague’s rehearsal. This allowed for some much-needed social time with discussion revolving around what we just saw and what we could implement into our own classrooms.

* Please note: many schools are more cautious due to COVID and other safety issues. Make sure to go through proper channels to visit other programs or invite visitors to your school.

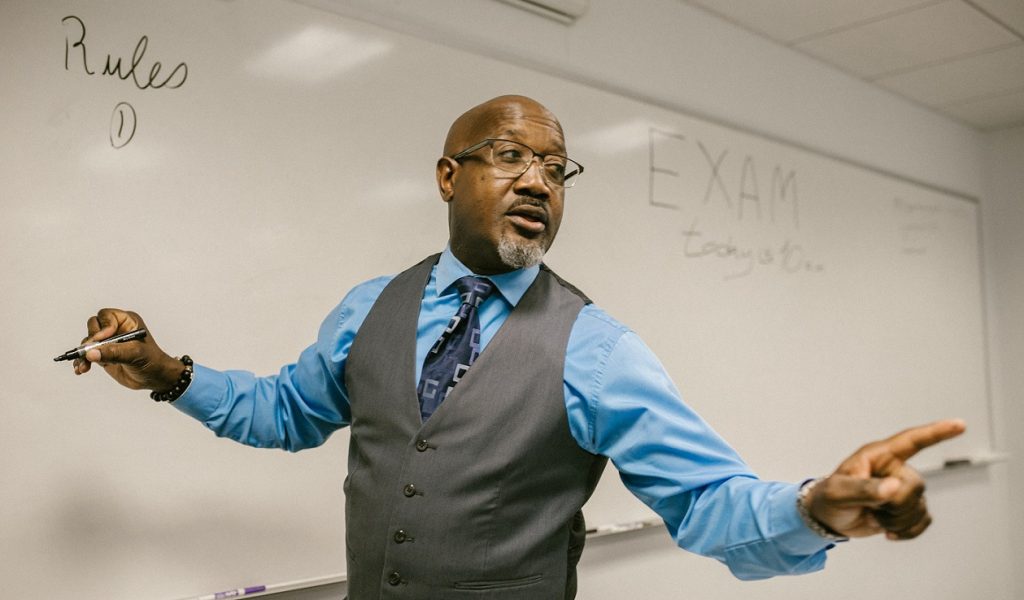

Take Control of Your Own Evaluation

In my more than 15 years of teaching, I’ve only been evaluated by an actual music teacher twice. Both times were extremely helpful. The other evaluations were completed by math, English and PE teachers. I certainly received some valuable information from these evaluations, but I missed out on some of the nuances that veteran music teachers can provide. If you are lucky enough to have an evaluator who is well-versed in music, take advantage of the situation and really absorb all their comments and advice. But if you’re in the same boat as me, consider scheduling an additional unofficial evaluation for yourself.

I have invited clinicians to my school to work with my group, but I never had someone come out to really dig into my teaching and conducting. I immediately thought of two music teachers who I would be most fearful of watching me teach — my high school band director, Mr. Ted Lega, and one of my mentors, Mr. Mike Fiske. After pacing around the room for a bit, I gave them a call. They agreed to come out the following week.

After many sleepless nights, the day came. I taught, and they watched without interruption. After the rehearsal, we had some time to sit down. I let go of my fear and ego and just listened. This turned out to be a transformative experience for me. I received so much practical advice, reinforcement of what was working, and suggestions for what needed to be changed to push myself forward. Some advice was simple, such as alternative approaches to setting up the band so certain sections could hear each other. Other suggestions were more significant. I had a lot of work to do with the tone of the group. They also suggested that we work toward an articulation that the entire group could agree on. It didn’t have to be the perfect articulation, but rather, consistent.

Figure Out What You Need First

Figure Out What You Need First

I knew that I needed significant help during my first few years of teaching, but I wasn’t sure about which specific areas. My goal was to have my group sound better — something we all want.

I had to do a little digging and self-reflection before asking for help. I eventually determined that I had some issues with teaching proper techniques for tone, intonation and articulation. I wrote down the different things I had tried and reflected on why they did or did not work so far. Then, I reached out to some colleagues and provided them with this information. This helped them tailor their advice to my specific needs so they could provide some practical advice on what could be added, tweaked or deleted from my approach. Furthermore, I hoped that this showed that I was willing to put in the effort and that their advice wouldn’t be wasted on me.

Try It for 30 Days

You have a couple of options once you receive advice from a friend, colleague or mentor. The first is to simply ignore it. The second is to try it out. After all, if you want different results, you have to do something different. Sometimes new methods, techniques and thought patterns take some time to work.

I will never forget a time in high school band when we sight-read a piece and it sounded pretty awful. One student said, “I don’t like this piece.” Without missing a beat, my band director, Mr. Lega, said, “Well, no one likes it the way we just played it.” We all laughed. A few weeks later, the piece turned out to be one of our favorites. It just took some time, discipline and consistency.

My general rule for a new technique or approach is to try it for 30 days. Sometimes, I record our first day trying out the new suggestion out, and then compare it to how the band sounds 30 days later. If I followed the technique correctly, and the group sounds better, we kept it.

My general rule for a new technique or approach is to try it for 30 days. Sometimes, I record our first day trying out the new suggestion out, and then compare it to how the band sounds 30 days later. If I followed the technique correctly, and the group sounds better, we kept it.

If not, we evaluate why it didn’t work. We either change something and try again or we move on to something else. I know that 30 days can be a long time to stick with something initially. I often get bored and want to abandon something new by day 15, but I work with my students on this, and we keep each other accountable. We understand that boredom and monotony can be a valuable part of the process.

The hardest thing to give up is our emotional attachment to warm-up exercises or rehearsal techniques that we grew up with. As a student, my band warm-ups were always an F Remington, scales and Mayhew Lake’s Bach chorale number 12. It took some rewiring of my brain to conclude that although these pieces felt good to me because they were familiar, it was not the only solution for my kids and my current teaching.

I teach at Joliet Central High School, the school I attended as a teenager, but the area has changed significantly. We now have band students from nearly 10 different sender schools in six districts and this doesn’t count the students who move in from other cities or states. I had to find and develop techniques and methods for the kids in front of me, not the bandmates I sat next to in the 1990s and 2000s.

Consider Multiple Mentors for Multiple Areas

Mentors are not one-size-fits-all. In fact, I have found it incredibly useful to have multiple mentors.

My mentors are great overall, but some excel in specific areas. When I have a marching band question, I contact a particular person. When I have a question concerning a situation specific to my school, I reach out to a friend who also works in a low-income/underserved school. I have another friend who doesn’t even work in music but who has been incredibly helpful with financial advice.

My mentors are great overall, but some excel in specific areas. When I have a marching band question, I contact a particular person. When I have a question concerning a situation specific to my school, I reach out to a friend who also works in a low-income/underserved school. I have another friend who doesn’t even work in music but who has been incredibly helpful with financial advice.

Thinking about changing jobs? Contact someone who has worked in a few different places. Maybe you have a work-life balance question. A colleague you know may have some helpful feedback in this area. Do you want to commission a piece for your ensemble but don’t know where to start? Take a look at some state and national convention programs and see who is premiering some commissioned pieces. Then, just email or call them with your questions.

Be careful about getting too many opinions about one area. I had questions in the past about some pretty big life decisions (or what I thought were big life decisions at the time…), and I contacted nearly everyone I knew. I wanted one answer, but I ended up getting more confused with feedback overload.

Ultimately, decisions regarding career choices, changing schools, family, etc., are up to you. Mentors, colleagues and friends can undoubtedly serve as a sounding board, but be careful of getting too much information, leading to paralysis by analysis.

Build Your Network

You are the one who has to do the work. However, you don’t live alone on an island. Ask for help because you don’t get more credit for figuring it out on your own. Expand your circle, seek specific feedback and implement advice from colleagues and mentors — you’ll find that with help, you can improve quicker than if you did this alone.