Tagged Under:

Use Movement to Fix Rhythmic Issues

Movement is often the most effective teaching tool to help students “feel” rhythm.

We have all had students who struggle to maintain a steady beat or who seem to not understand metric relationships. They compress rhythms or slow down during more challenging passages.

The main reason students struggle with rhythm is because they haven’t experienced a rhythmically diverse foundation and developed a rhythm vocabulary. While clapping and playing with a metronome can fix some things, for students who do not feel rhythm, movement is often the most effective teaching tool.

In my movement pedagogy and in this article, I like to synthesize the work of Émile Jaques-Dalcroze and Edwin Gordon, sprinkled with a little Rudolf Laban.

- Émile Jaques-Dalcroze (1865-1950), a Swiss composer and music educator, developed Eurhythmics, or the study of music through movement.

- Edwin Gordon (1927 – 2015) was a performer, music educator, researcher and author who established Music Learning Theory, a model for music education based on how children learn when they learn music. He also coined the term “audiation” – hearing and understanding music in one’s head, even when there is no music present.

- Rudolf Laban (1879 – 1958), an Austrian-Hungarian dancer, choreographer and movement theorist, created Labanotation, a dance notation that allowed dances to be restaged. He also researched the basic principles of human movement, classifying them into four main parts.

Although these three creative men differed in many ways, they agreed that movement and music are intertwined. I won’t dive too deeply into their philosophies and pedagogies here because I want to focus more on practical application, but I encourage you to read more about them.

Rhythmic Patterns

Music educators all agree that the sound should come before the symbol. Unfortunately, it’s far too easy to just open a method book and teach the symbol first. Often rhythmic problems can occur because a student just isn’t sure what those dots sounds like – they have no real meaning to the student. In Music Learning Theory, Gordon advocated for the use of rhythmic patterns prior to reading rhythmic notation.

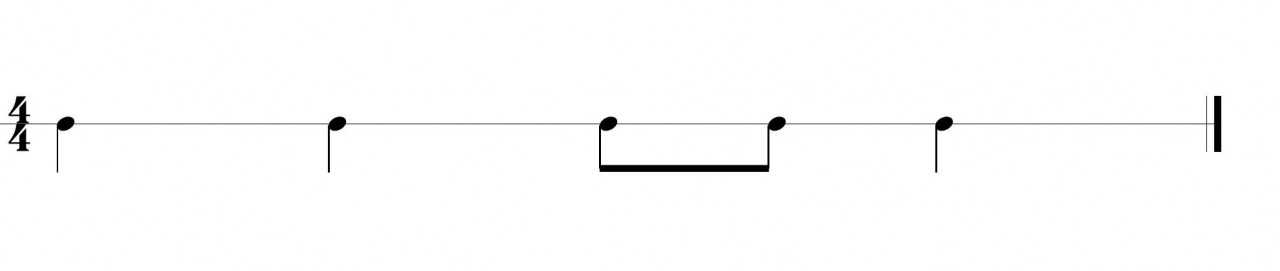

In his theory, there are specific rules for creating the patterns, but for now, let’s just use a simple pattern of quarter, quarter, eighth, eighth, quarter in 4/4 time (see pattern to the right). As the teacher, I would start by using a neutral syllable like “bah, bah, bah-bah, bah.”

In his theory, there are specific rules for creating the patterns, but for now, let’s just use a simple pattern of quarter, quarter, eighth, eighth, quarter in 4/4 time (see pattern to the right). As the teacher, I would start by using a neutral syllable like “bah, bah, bah-bah, bah.”

I can either create different patterns and have the student repeat them back to me or I can chant two patterns and have the student tell me if they are the same or different. If the student cannot determine whether my patterns are the same or different, I know that they are not quite ready to audiate the meter and its subdivisions. So, we continue working on repeating patterns. After adding rhythmic solfege to the patterns and having the student create their own patterns, the notation or symbol makes more sense because the student already has the sound in his or her head. The timeline for this is different with each student.

Big Beats and Little Beats

One of the most common rhythmic problems I encounter is playing steadily in 3/4 time. Unfortunately, most of the music on the radio and most of the music in early method books is in 2/4 or 4/4 time, so switching to triple meter can create problems. (While not directly movement-related, improvising in the “troublesome” meter can be a great help.)

One of the most common rhythmic problems I encounter is playing steadily in 3/4 time. Unfortunately, most of the music on the radio and most of the music in early method books is in 2/4 or 4/4 time, so switching to triple meter can create problems. (While not directly movement-related, improvising in the “troublesome” meter can be a great help.)

When a student struggles with playing with a steady beat or compresses running notes, it is usually because they do not understand the relationship between the big beats and the little beats. (Gordon calls big beats “macrobeats” and the little beats are called “microbeats.”)

To help a student with this problem, I will improvise a piece in 3/4 time and ask them to sway back and forth or walk around the room to the macrobeat. I like swaying or walking better than clapping because these movements show the time and space that also exists between the beats, not just on the beat. (If you are not comfortable improvising, you can always use pre-notated music or sing or use a recording.)

To incorporate the microbeats, have the student tap their fingers on their head or shoulders. When they can accurately feel the macrobeats and microbeats individually, ask the student to sway the macrobeats while tapping the microbeats. Again, this is helping the student to really feel the subdivisions.

I have also seen Dalcroze teachers use tennis balls to work on this concept. The teacher plays a piece with changing tempi while the student bounces the ball on the macrobeat. The microbeat actions might be passing the ball to another hand, tossing it. (Using the tennis ball also makes the student pay attention to how much force or accent is needed on each downbeat.)

I have also seen Dalcroze teachers use tennis balls to work on this concept. The teacher plays a piece with changing tempi while the student bounces the ball on the macrobeat. The microbeat actions might be passing the ball to another hand, tossing it. (Using the tennis ball also makes the student pay attention to how much force or accent is needed on each downbeat.)

I work in a similar way with students who are compressing subdivisions or rushing through 16th note runs. I also like to have them “play” on the closed keyboard cover so they can hear the clarity of the rhythm without worrying about correct notes, dynamics, articulation, etc.

Body Percussion

With older children, body percussion is a fun way to work on complex rhythms or polyrhythms. One of my favorite body percussion activities is a rhythm canon, demonstrated in this video by Dr. Jeremity Dittus. Michelle Wirth also has some great activities on her website, Body Percussion Classroom. I have used her Simple Three-Part Rhythm in conference presentations, with young children and even with my college students, and they all have a great time.

With older children, body percussion is a fun way to work on complex rhythms or polyrhythms. One of my favorite body percussion activities is a rhythm canon, demonstrated in this video by Dr. Jeremity Dittus. Michelle Wirth also has some great activities on her website, Body Percussion Classroom. I have used her Simple Three-Part Rhythm in conference presentations, with young children and even with my college students, and they all have a great time.

You can also have students create their own body percussion ensembles to address specific rhythmic issues. A great opportunity for body percussion is the 3:2 rhythm that occurs in Debussy’s “First Arabesque.”

Of course, listening is the most powerful tool and we should encourage our students to listen to a variety of musical styles. There will always be students who struggle, though, and I hope that these tips will help you and your students as you travel on your musical journey together.