Tagged Under:

10 Tips for Teaching Students with Autism

Teaching students who are on the spectrum is a fulfilling challenge as long as you are prepared and flexible.

Autism (or autism spectrum disorder) is a pervasive developmental disorder that affects 1 in 54 children in the United States, according to a 2020 report from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Because autism is a spectrum disorder, no two children are alike and deficits range from low-functioning (no vocabulary, not toilet-trained, needs help with feeding) to high-functioning (able to hold a job and drive a car) and everything in between. These children experience deficits in three areas:

Communication — deficits include one or more of the following: very little or no spoken language, lack of conversational skills, echolalia or repetition of others’ words and no make-believe or imitative play.

Communication — deficits include one or more of the following: very little or no spoken language, lack of conversational skills, echolalia or repetition of others’ words and no make-believe or imitative play.- Social Skills — deficits include two or more of the following: lack of eye contact or facial affect, inability to develop peer relationships and lack of interest in sharing joy, interests and achievements with others.

- Behavioral Skills — deficits in this area are exhibited in one or more of the following ways: preoccupation with one or more patterns of interest that is abnormal either in intensity or focus, adherence to certain routines/rituals and difficulty adjusting to changes or transitions, repetitive motor mannerisms (such as hand flapping or finger flicking) and preoccupation with parts of an object.

With the prevalence of autism, there’s a high probability that you will have students who are on the spectrum. I began teaching students with autism in 2001 as a graduate student and have continued working with this population ever since, which has helped me grow so much as a musician and teacher. I’d like to share 10 basic tips that can help you feel more comfortable teaching students with autism, including:

- Tip #1 — Use Person-first Vocabulary

- Tip #6 — Be Aware of Distractions in the Environment

- Tip #8 — Don’t Get Stuck on Note Names.

1. Use Person-First Vocabulary

Say “a child with autism” rather than “an autistic child.” This might seem like a small and unimportant distinction, but to the child and his or her parents, this is a big deal.

Say “a child with autism” rather than “an autistic child.” This might seem like a small and unimportant distinction, but to the child and his or her parents, this is a big deal.

Person-first vocabulary means that we recognize that the child is a person first who happens to have a development disorder. You might surprise yourself and find that your way of thinking changes, too.

2. Each Child is Different

I am sharing some general tips that will help guide your teaching approach. Some methods you try will be successful with one student and will completely fail with another. Also, things you try might work one week and not the next.

Just as every typically developing child is different, every child with special needs is, as well. If something doesn’t work, don’t give up on your plan or the child — that particular teaching strategy just didn’t work that day.

Each child is different, and each day is different.

3. Don’t Assume Anything

Start from square one. Many children with autism like to play piano with just their index fingers. They might not even be aware that they have other digits to use or that those digits are called fingers.

On the other hand, many children with autism have really great ears and can play difficult songs by ear.

Start with the very basics. Break every new concept or activity into achievable steps.

4. Use Clear, Concise Language

Students with autism are very literal in their understanding of language and don’t necessarily make transfers easily. Give directions that tell them exactly what you want them to do and how.

For typically developing students, I might reference a seesaw or “sticky fingers” when teaching them how to play legato and describe it as playing the keys with gum on their fingers. However, for a child with autism, that imagery would not be helpful.

Instead, I would demonstrate and explain to students with autism how the first finger remains down on the key until the second finger plays the next note. Or, I would slowly move their fingers up and down and even help them with their fingers until they understand the coordination. (Remember to always ask permission before touching a student.)

Also, avoid using multiple terms for the same concept, such as thirds, skips, line to line, space to space — all of which describe the same concept.

5. Establish a Routine, Which Allows for Flexibility

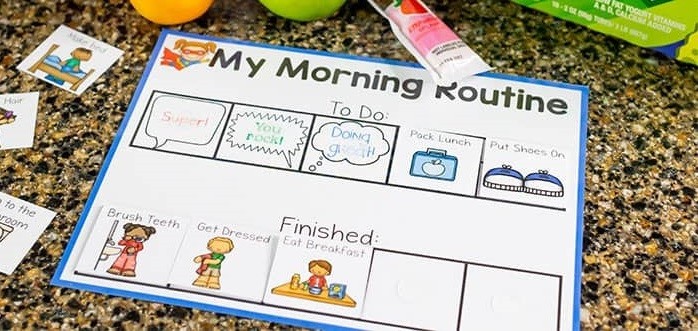

Some children with autism are used to using picture schedules (see photo to the right) at home or school, and I often incorporate that into lessons. (You can easily make one with Velcro and poster board.) Others like to begin and end with the same song but are able to have more flexibility during the lesson. An example of a sample lesson would include: 5-Finger Patterns, Improvisation, Repertoire Piece, Notes Names, Student’s Choice, “Hokey-Pokey.”

Some children with autism are used to using picture schedules (see photo to the right) at home or school, and I often incorporate that into lessons. (You can easily make one with Velcro and poster board.) Others like to begin and end with the same song but are able to have more flexibility during the lesson. An example of a sample lesson would include: 5-Finger Patterns, Improvisation, Repertoire Piece, Notes Names, Student’s Choice, “Hokey-Pokey.”

It’s good to have a set structure and lesson plan, but sometimes something triggers the student, and the plan needs to change. Or, the student is doing really well at something and requires a new plan.

Breaks are also very helpful and can still incorporate musical aspects. For example, try a movement activity or dance break, even flashcards away from the piano. Be flexible with lesson length, as well. With the same student, I have had lessons that are 20 minutes and lessons that are one hour.

6. Be Aware of Distractions in the Environment

Most children with autism have sensory processing difficulties. A shirt made of itchy material or the humming of a light can make it hard for them to focus. Changes in the environment can also be unsettling. Before a student with autism arrives, I make sure that my studio is clean and that any distractions, including teaching manipulatives, are out of sight.

7. Tackle One Issue at a Time

It can be overwhelming for any student to try to think about notes, hand position, rhythm, pedal, etc. at the same time. Students with autism sometimes need more processing time, so don’t try to change everything at once. Work on getting the student to use all of their fingers. Then you can talk about rhythm (teach rhythms aurally!) or dynamics or something else.

8. Don’t Get Stuck on Note Names

Note-reading is not the most important part of music. Some children with autism might learn to read note names while others might not, and that is OK. Use familiar music. Teach aurally. Ask for input from students as to what kind of music they would like to learn.

Some children might never reach the stage of polishing and perfecting a piece, and that is OK. Performing at a recital may not be a motivating factor for a child with autism. It could even have the opposite effect.

Although, learning and progressing are important for us as teachers, we want to make sure that the musical experience students with autism receive is positive and uplifting.

9. Parents Are Your Biggest Resource and Fans

Nobody knows your student better than their parents. If you get stuck, ask how they work on new skills in the home or what they use to help motivate their child. Parents of children with special needs are unfortunately used to having their child excluded from activities on a regular basis, so to have someone invest time and energy in their child’s success is a wonderful thing.

I remember one parent telling me that her child had been kicked out of soccer and swimming and that piano was his only extracurricular activity. This parent also gave me tools for helping to redirect the student if he got distracted and encouraged me to include a fun song at the end of every lesson. For this child, it was “Hokey-Pokey”.

10. Be Patient with Yourself and Your Student

Don’t take it personally if something doesn’t work right away or if a student doesn’t respond in the way you predicted. We all have bad days and, for a child with autism, there are so many factors that can affect their reactions.

Dr. O. Ivar Lovaas, a clinical psychologist known for his work with children with autism, said, “If a child does not learn in the way we teach, we must teach in the way they learn.” Challenge yourself to step out of your comfort zone and reach out to someone who might learn and process information differently than you do. In doing so, you might change their world and yours, too.