Bob Malone: A Look Back on a Storied Career Designing Yamaha Trumpets

The Director of Yamaha Winds Atelier and Artist Relations prepares for a new chapter.

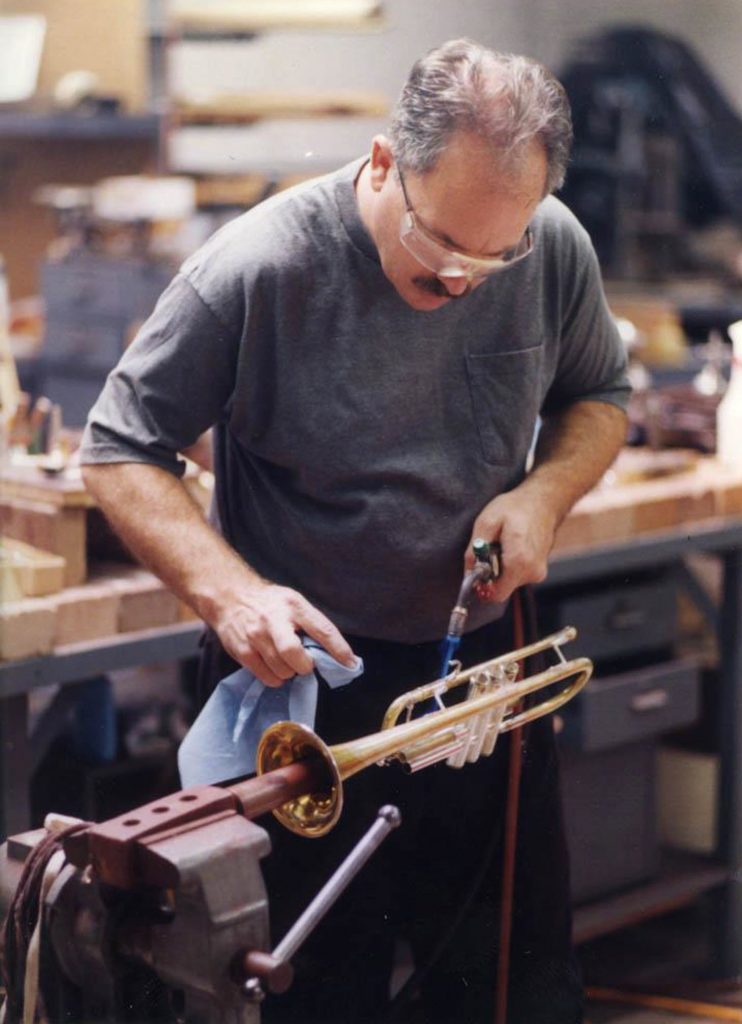

In Bob Malone’s shop, there’s no such thing as a generic instrument. In almost 40 years of designing and modifying Yamaha horns — 21 of those years working directly for the company — Malone has become known for his design collaborations with such artists as Bobby Shew and Wayne Bergeron, among many others. But beyond the artist credits to his name, Malone has helped change how Yamaha develops instruments. Instead of designing a prototype and seeking artist input later, Malone helped pioneer a process of consulting first with the artist — often one specific, elite artist — and tailoring the instrument around that artist’s needs. His approach yields instruments linked indelibly to one musician’s personality and playing style, but with elements that enrich whole product lines and inspire musicians at all levels, like a star athlete’s signature shoe that becomes a favorite with aspiring players across the sport.

A Craftsman’s Career Begins

A trumpet player since grade school, Malone initially pursued a performance career with a sideline in instrument repairs and modifications. That sideline would become a lifelong calling. After starting out under renowned brass technician Larry Minick, Malone started his own business, Bob Malone’s Brass Technology, in 1983 — quickly earning a sterling reputation for his craftsmanship. Originally working out of a space in Minick’s shop, he opened his own facility in Southern California in 1987.

Soon afterward, he formed a relationship with Yamaha: first becoming a Yamaha dealer, then performing authorized Yamaha repairs, and eventually landing the career-changing assignment to develop the famed Z Trumpet alongside Shew and legendary Yamaha designer Kenzo Kawasaki.

In 2001, Malone was brought into the company and was sent to Grand Rapids, Michigan, where he helped form the Yamaha Custom Shop. In 2003, he was part of the group that selected and designed Yamaha’s showpiece New York City atelier offices. He was essential to the creation of the Xeno Artist Model line of B-flat and C trumpets developed with orchestral greats John Hagstrom, David Bilger, Thomas Rolfs, Robert Sullivan, Håkan Hardenberger, Tom Hooten and Chris Martin. He also provided wind instrument technical support to Tower of Power, Snarky Puppy and Big Bad Voodoo Daddy, working with the bands’ entire horn sections to facilitate instrument selection and modifications. While trumpets will always be nearest to Malone’s heart, he’s also brought his signature approach to the development of key Yamaha trombone, flugelhorn, French horn and tuba products, as well as creating a patented clarinet barrel.

A Conversation About Collaborations

Now once again based in Southern California as the Yamaha Corporation Director of Winds Atelier and Artist Relations, Malone is looking toward a new phase in his career. Not yet ready to retire, he’s carved out a role where he can focus solely on the creative side of his work. With new projects in his sights, Malone talked with us about some of his favorite collaborations and what they’ve meant for a generation of horn players.

Q: In general, what’s your approach to developing a horn for an elite artist?

A: At that level, they know what their sound is. They have an identity. So you’re trying to give them an instrument that allows them to be them, but in a way that’s easier to play and offers them more possibilities.

You’re trying to give the artist the freedom to create. They have a musical idea. You want the instrument to be almost transparent, and not get in the way of that idea — so they’re not having to think about mechanics or intonation or needing to manipulate anything as they play.

Q: What was it like working with Bobby Shew? What did he need in an ideal trumpet?

A: Bobby is such a unique player. He’s obviously a great jazz player, but he’s also known for being an incredible lead player who plays effortlessly in the upper register. So we had the challenge of creating an instrument that would work really well in both areas. He had developed this concept of playing that was really based on efficiency, so he needed an instrument that matched what he was trying to do. The Z Trumpet was the result.

Q: How did the process behind the Z Trumpet change how Yamaha develops instruments?

A: Yamaha had earned a great reputation for quality manufacturing. But their process for developing new instruments was mostly internal: putting together a prototype and then taking it out and having players try it, taking notes on their reactions, and making changes based on that feedback. The criticism was that even though the instruments really played in tune, were easy to play, and had high-quality manufacturing, they didn’t have any personality.

The Z project may have been the first time Yamaha didn’t do that. They identified a player, and the idea was to make an instrument that he would be 100% happy with. Since it wasn’t designed by a committee but was based on a particular person — a really well known, well respected artist — we ended up with a trumpet that had personality: Bobby’s personality. From that point on, virtually all of the development projects that we’ve done involving pro or custom instruments have had a development artist associated with them.

Q: What about the L.A. Trumpet, the model you developed with Wayne Bergeron? How was that different?

A: Wayne and I have known each other for a long time. We met while playing out at Disneyland, and we’ve been friends ever since, so we had a really good base from which to work together.

The Z Trumpet was a great trumpet that satisfied a lot of players, but it didn’t satisfy a certain kind player, and Wayne really represented that type of player. He’s a very physical player. At the end of the night, after the second or third set, when he was really tired, he wanted a trumpet that wouldn’t force him to be “efficient.” As he put it: “I want to be able to fight myself off the ropes. I want to be physical with it and not have the trumpet hold me back.” He needed a trumpet to match his style of playing, so we went back to the drawing board and ended up with a trumpet that was him.

Q: You needed a different approach with elite orchestral players. What’s the story behind the Yamaha Xeno Artist Model Trumpets?

A: I had known John Hagstrom of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra since he was out in California playing with the Disney All-American College Band, and I’d modified virtually every instrument that he was playing. I asked John if he’d be interested in helping Yamaha develop a new C trumpet. He said yes, and we started on a path of discovery to build an instrument that would be a preferable choice for players in a symphony orchestra. That ended up being the Chicago C Trumpet.

That was the first Artist Model trumpet, and there were lots of twists and turns in developing it. At one point the orchestra was on tour in Switzerland, and Daniel Barenboim was the conductor. In front of the orchestra, they did a playing test between our Yamaha prototype and another well-known trumpet brand, playing them both back and forth … and Barenboim chose the Yamaha. That was a really important moment in our development of that horn. It went into production, and I think for a period of time it was used to win more trumpet auditions than any other model.

We went from almost no presence in the major orchestras to a dominating presence. The entire Boston Symphony and Philadelphia Orchestra play Yamaha trumpets now — not to mention players in the New York Philharmonic, the L.A. Philharmonic, and the list goes on.

Q: What’s unique about doing this kind of work with Yamaha?

A: It goes back to the core values that made me join Yamaha in the first place. It’s the way Yamaha values the development process and strives to create the best instruments, at every level. For a student, it’s giving them something that isn’t going to get in the way of their progress. The idea of creating more music makers is huge. With a professional player, it’s giving them an instrument that will allow them to fully develop their musical ideas without getting in the way, giving them new possibilities.

One of the big differences between Yamaha and other companies is on the R&D side. They have designers assigned to every instrument, and those designers go to work every day thinking about how to make these instruments better. And it’s supported from the top on down — from the executives all the way down into the trenches where these development sessions take place.

Q: You’re now moving into a different kind of role with Yamaha. What will that entail?

A: I’m pretty excited about it. I’m stepping into a consultant role where I’m giving up my administrative responsibilities and I’ll be able to focus on development projects: working with artists, mentoring staff. The agreement makes me available both here in the U.S. and globally. It’s allowing me to transition into retirement a little more gradually, and we’ve got some exciting projects that I’d love to still be involved with. I’m looking forward to it.

Insights from a Master: Great Instrument Qualities

How do you build a great musical instrument? For Malone, the X factor is creating the instrument that becomes “transparent” in the player’s hands: “You want that instrument to let them project their voice without thinking about it,” he says. “The creative process doesn’t get filtered out through the instrument. Their focus stays on the creative side, and not on how to overcome this or that deficiency.”

If that’s the “secret sauce,” what’s the basic recipe? You can start with these four essentials, according to Malone:

- Intonation: “When the horn has a problem with intonation,” he says, “compensating for that problem can become subconscious for the player — pushing a certain note up because it’s flat, let’s say. But with an instrument that plays in tune, the player doesn’t have to do that. It puts less stress on them, and they don’t tire as quickly because they’re not having to manipulate so much. At the same time, you want to create an instrument that’s flexible, because in the real world, you’re playing with ensembles where the pitch may vary, and you need flexibility to push the pitch one way or the other.”

- Quick response: “You want the instrument to be agile — to react in the musical moment. If you watch a great jazz quartet, there’s so much communication going on between the players. They’re reacting against what the others are doing. You need an instrument that responds quickly so you can have that musical conversation.”

- A “blow” that feels good to the player: “You want the instrument to meet the player where they’re at. You want the balance of resistance to match what that player needs. If that isn’t right, there are lots of problems that can develop. One is fatigue. Another is that the instrument won’t resonate properly. It may not have the same uniform color or sound as you go from the bottom register to the top register.”

- A signature sound: “The signature sound is relative to the player, not the instrument. There are a lot of instruments out there that may play in tune, may be easy to play — but there’s no flexibility, no opportunity for the player to project who they are. You want flexibility. You want transparency. You want the artist’s sound to come through.”

@yamahamusic The special cryogenic process that we use with brass instruments releases the stress in the metal caused in production. It breaks in the instrument and brings out the characteristics of its sound. #YamahaMusic #Yamaha #Trumpet ♬ original sound – Yamaha Music