Yanny vs. Laurel: Perception Is Reality

The ear can play tricks, too.

In a previous posting, I discussed the physical aspects of how a sound is created. This month, I want to talk about the other half of the equation: the way we perceive a sound.

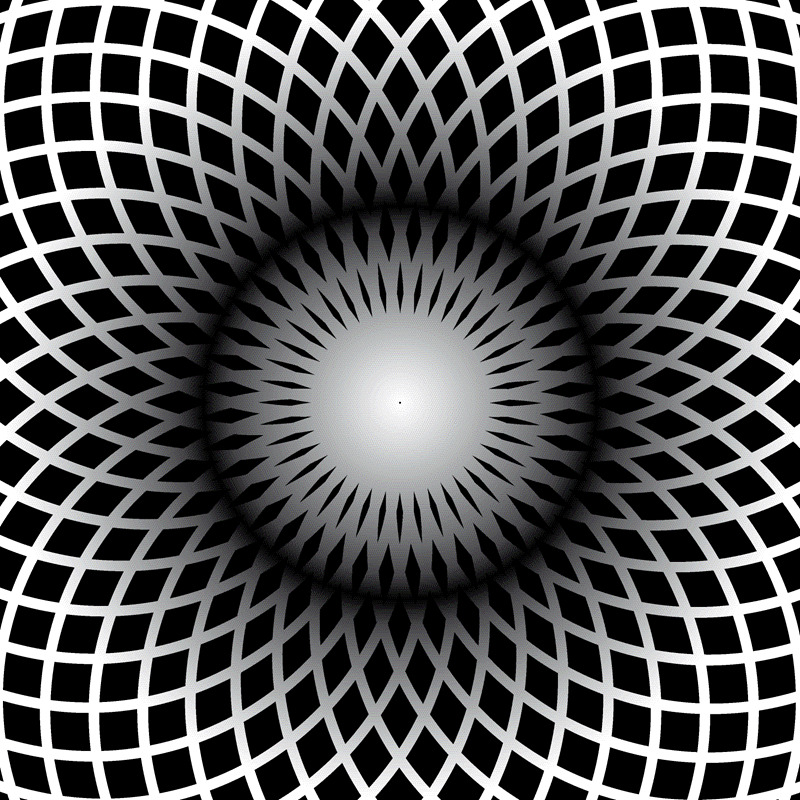

Most of us are familiar with optical illusions — visual anomalies that seem real, but are in fact just trickery. Two examples that are part of our everyday lives are television and movies, both of which are actually a series of still pictures moving so fast that we perceive motion that isn’t actually there. Or check out the image on the right. Does it seem as though some of the black and dark gray circles in the middle are moving? They’re not. This isn’t an animated GIF, or a video: it’s just a plain old JPEG. But due to the physiology of our eyeballs and optic nerves, many people will swear that those circles are pulsating.

There’s an argument to be made that if you see motion, then there is motion, even if the facts say otherwise. It’s a hypothesis that can be summed up in three words: Perception is reality.

Or are only facts reality … even if your perception says otherwise?

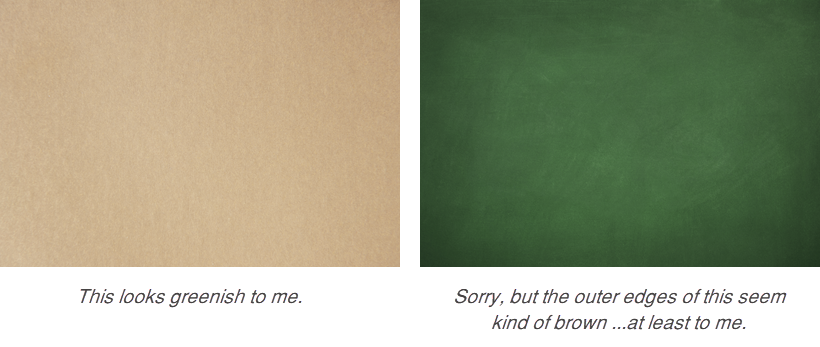

I happen to suffer (well, “suffer” is really too strong a word) from a mild form of something called deuteranomaly — a fancy word for the common affliction of being red-green color blind. Most brown objects appear green to me, and a lot of green objects appear beige, brown or even black, depending upon how light or dark they are. This has been the source of endless debate with my Significant Other, who once stopped me from purchasing what I believed was a cool-looking mint green car on the grounds that she wouldn’t be caught dead riding around in a vehicle she described as being painted a “nauseating shade of putty.”

Yet that car was green to me, despite what S.O. (and, according to her, the rest of the world) thought.

So was it a cool shade of lime green, or a nauseating shade of putty? The battle rages on. But the point is that the eye can definitely play tricks on the brain. Did you know the ear can, too?

Sure you do, at least if you expressed any interest in the Yanny/Laurel meme that was consuming social media not long ago. In case you were hiding in a cave, here’s what the fuss was all about:

What did you hear? “Yanny”? Or “Laurel”?

If you listened to it on your smartphone or earbuds, you probably heard “Yanny.” But if you listened on a reasonable quality speaker — even a small computer speaker — you most likely heard “Laurel.”

What the heck is going on here?

Let’s take a look at the facts. This was actually a recording of an actor saying the word “laurel,” created for the dictionary entry of the same name on the vocabulary.com website. However, if you listen to the high frequency content in the recording alone — which would happen when listening on earbuds or poor-quality speakers incapable of reproducing low frequency content — it sounds eerily like the word “Yanny” instead. (Whoever this Yanny guy actually is.)

Don’t believe me? Check out the New York Times online tool that lets you literally dial in the point at which Laurel magically changes to Yanny. (There’s also a good explanation there about how this whole craze likely got started.)

This is a great example of an auditory illusion. Another famous one is the Shepard Tone, named after cognitive scientist Roger Shepard. This is a sound consisting of a series of simple sine waves (pure tones with no overtones) an octave apart but with the bass pitch moving upward or downward. It creates the illusion of a tone that continually ascends or descends in pitch, yet ultimately seems to get no higher or lower — an endless scale that in some people induces queasiness or even headaches. If you’re as much of an auditory nerd as composer Hans Zimmer (who famously used Shepard Tones to great effect in the film Dunkirk to create the sense of ever-increasing intensity across intertwined storylines) and you feel like playing around with this on your own, you can find a way cool interactive online ST generator here.

Neuroscience has proven that our auditory (and visual) perception is affected by a wide range of factors. We may think we perceive the world around us as it really is, but our brain is actually a massively complex filter, and every brain is wired slightly differently.

In other words, hearing occurs in the ear, but listening occurs between the ears. Take that into consideration the next time a parent or a friend gives you a hard time about the music you are passionate about … or the next time you feel like disparaging the tunes that they love.