Celebrating Diversity

The contributions of black composers and performers to American music.

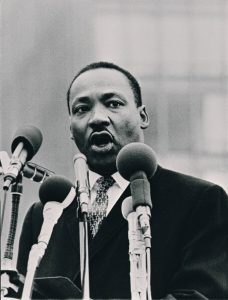

“Everybody has the Blues. Everybody longs for meaning. Everybody needs to love and be loved. Everybody needs to clap hands and be happy. Everybody longs for faith. In music … there is a stepping stone towards all of these.”

Those are the words of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at the Berlin Jazz Festival in 1964. As we celebrate King’s many accomplishments (including the Nobel Peace Prize he won that year), it’s a good time to reflect on the contributions of black composers and performers to American music.

Black composers and performers thrive on the creative DNA of the survivors of the transatlantic slave trade who brought with them the drum patterns and polyrhythms that influence and inspire all modalities of black music. Our story begins with the blues, a genre that began in the cotton fields of the Deep South throughout the late 19th century as musicians channeled African spirituals, chants, work songs and hymns into narratives that spoke to their condition. A pivotal figure was the composer and cornet player William Christopher “W.C.” Handy, considered “father of the blues.” Handy toured the Midwest and the South extensively, popularizing the style and exposing audiences to his particular brand of the 12-bar blues.

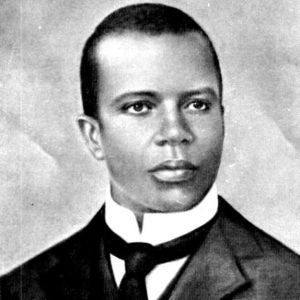

In the latter part of the century, a piano-driven medium called Ragtime began to take shape, as exemplified by the popular tune “The Entertainer,” written by composer and pianist Scott Joplin in 1902 — a song that found a new life on the soundtrack for the award-winning film The Sting in 1973. Another piano man of the era, Jelly Roll Morton, straddled ragtime and jazz, gaining prominence through recordings he made with his group Morton’s Red Hot Peppers.

The next major superstar in black music was vocalist and trumpeter Louis Armstrong, who first rose to prominence in the 1920s. “If you love jazz, you have to love him,” said trumpeter and bandleader Wynton Marsalis on Armstrong’s importance. Louis Daniel “Satchmo” Armstrong is considered one of the greatest jazz soloists ever. Some critics have made the observation that he played “beyond the notes,” creating intricate layers of feeling and nuance. What is inarguable is that he influenced every jazz musician who came after him. This was particularly evident with saxophonist Coleman Hawkins. While the pair played in Fletcher Henderson’s big band in 1924, Hawkins took note of Armstrong’s patience during solos, his use of silence for dramatic effect, and his unique phrasing, and later used those techniques to later develop his own recognizable sound.

And then there is Duke Ellington. The iconic trumpeter and jazz architect Miles Davis is credited with saying, “At least one day out of the year all musicians should just put their instruments down, and give thanks to Duke Ellington.” That’s not an overstatement. Edward Kennedy Ellington was one of the most consequential composers and bandleaders of the 20th century. He wrote thousands of songs and was a deft pianist, but his true instrument was his orchestra — an ever-changing cast of star musicians he led for over 50 years, often financing their expenses out of his own pocket. Among his enormous catalog, some of the Ellington Orchestra’s most well-known hits include “In A Sentimental Mood,” “I Got it Bad And That Ain’t Good” and their signature tune, “Take The A Train,” written by arranger Billy Stayhorn. But Ellington’s contributions to music and culture don’t end there. From 1965 to 1973 he wrote three lengthy compositions that fused elements of jazz, classical, choral music, spirituals, gospel, blues and dance — “sacred concerts” that were presented to audiences in churches and cathedrals across the globe.

As the big band era, dominated by figures like Ellington and Count Basie, began to fade in the mid-1940s, a group of younger and aggressive players began to put their imprint on jazz. The trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie was at the forefront of the Bop era, not only for his compositions and improvisational skills, but his willingness to mentor other musicians, including Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Clifford Brown, Lee Morgan and Arturo Sandoval. The era was also shaped by the contributions of drummer Kenny Clarke, guitarist Charlie Christian, saxophonist Charlie “Bird” Parker, and pianist Thelonious Monk.

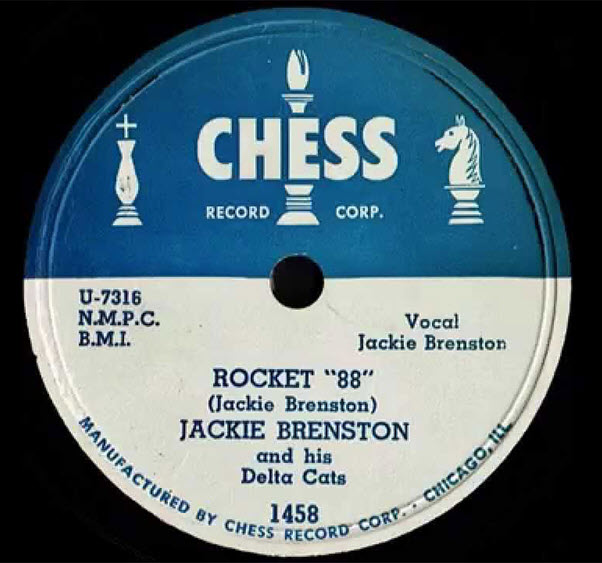

Images of Elvis Presley or Bill Haley and the Comets may come to mind when thinking about early rock’n’roll, but most music historians point to “Rocket 88” — ostensibly by “Jackie Brenston and his Delta Cats” but in reality sung by Ike Turner (later of Ike and Tina Turner fame) — as the first rock record. Its up-tempo danceable pace set the framework for similar works by the likes of Chuck Berry, who gave the world unforgettable tunes like “Johnny B. Goode” and “Maybellene,” and Little Richard, whose high-tenor vocals and high-energy stage antics wowed crowds with “Tutti Frutti and “Good Golly Miss Molly.”

The 1960s saw the rise of Motown — the Detroit-based record label founded by Berry Gordy with the explicit aim of popularizing black music to the nation as a whole. For more than a decade, the company nurtured a roster of songwriting, producing and vocal talent that was staggering. Motown exported its unique brand of R&B through artists like the Supremes, the Temptations, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, Smokey Robinson and, later, The Jackson 5, singing hit after hit by the songwriting team of Holland-Dozier-Holland and other composers.

In the late 1960s, innovative guitarist Jimi Hendrix came to prominence. Hendrix had served apprenticeships with both the Isley Brothers and Little Richard, but those were mere footnotes for a musician who expanded the possibilities of his instrument through the use of effects and feedback. He was also a master showman who could play guitar with his teeth and behind his back … and famously set fire to his instrument at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967. Hendrix’s life was cut short tragically at an early age but his experimentation with funk and blues set the path for later artists like George Clinton, Prince and Living Colour.

Rap and hip-hop are two genres dominated by black artists. Ever since the seminal 1979 hit “Rapper’s Delight” by The Sugarhill Gang, practitioners have steadily moved beyond simple party rhymes to addressing serious social and political issues. Some of rap’s most influential storytellers include Public Enemy, A Tribe Called Quest, NWA, Eminem, Mos Def, The Notorious BIG, Tupac Shakur and Snoop Dogg. In 2017, Jay-Z (Shawn Carter) was inducted into the Songwriter’s Hall of Fame and LL Cool J (James Todd Smith) received a Kennedy Center Honor; just last year, the rapper Kendrick Lamar won the Pulitzer Prize in music. This marked the first time the award went to a non-classical or jazz musician — an amazing achievement for a genre that was once derided by critics.

Sometimes performances by black artists are less about the art they make and more about the symbolism behind them. In 1939, opera singer Marian Anderson was dragged into a fight about segregation between a group called the Daughters of the American Revolution and then-first lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Anderson was invited to sing in Washington by Howard University, and the only venue large enough to accommodate the crowds was Constitution Hall — a venue that had instituted a whites-only policy. Roosevelt, a DAR member, was furious and canceled her membership. When the group refused to change their policy, the concert was instead held on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, with a desegregated crowd of 75,000 in attendance.

And this brings us to another defining moment at the Lincoln Memorial. The gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, who was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1997, played a pivotal role in Dr. King’s historic speech at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. Often called “The Queen of Gospel,” she moved the massive crowd (over 300,000 strong!) with her renditions of “I Been ’Buked and I Been Scorned” and “How I Got Over.”

However, Jackson’s role at this event far outweighed the power of her vocals. Drew Hansen, author of “The Dream: Martin Luther King Jr., and the Speech That Inspired a Nation,” wrote in a 2013 New York Times article that King initially thought he wouldn’t have time to use the “I have a dream” imagery in his remarks. As he neared the end of the speech, King implored the crowd to return to their communities (“Go back to Georgia; go back to Louisiana; go back to the slums and ghettos of our Northern cities”) with the hope that America’s racial conflicts would be resolved. It was at this point that Mahalia Jackson, seated nearby, shouted, “Tell them about the dream, Martin.” What followed became some of the most famous lines in American oratory.

Perhaps the greatest contribution of black composers and performers has been their ability to bring our nation together. Sometimes in song, sometimes in protest, sometimes on the dance floor … but always to heal our wounds and celebrate our love.