A Guitarist’s Guide to Playing Bass

How to transfer your skills from the six-string to the four- (or five-) string.

Let’s face it: Most guitarists don’t give bass the respect it deserves.

“How hard can it be to play?” many of them say (or think). “After all, it’s got fewer strings than guitar, and you mostly just play single notes on it.”

I don’t subscribe to that notion at all. Besides, as a songwriter and composer, I love changing the bass notes in a chord to create interesting harmonic progressions … and those powerful notes sound even better when played on a bass.

In this posting, we’ll take a look at how the average guitarist can easily transfer their guitar-playing skills to bass.

The Bassics of Bass

Let’s start with some of the “bassics,” if you’ll pardon the pun. The open strings on a four-string bass are the same as on guitar (E, A, D, G), only tuned an octave lower. For that reason, all the scales and arpeggios you already know on your guitar can easily be played on the bass, because they have the same exact shapes, although the wider fretboard and fret spacing means you’ll have to spread your fingers a bit more. However, you won’t have to deal with that awkwardly tuned B-string major third interval skip, or the high E string! So in effect, all your shapes become a lot easier to play and memorize. And yes, you can even use your beloved major and minor pentatonic scales to create basslines. (See below for more about this.) In fact, lots of dedicated bass players love using those kinds of scales.

In addition to the fretboard being wider and the frets further apart, the scale length is longer, and the strings are much thicker. These differences may take a little getting used to, but with repetition and practice, the muscle memory of both your hands will adapt over time.

Although you can play double stops and even full chords on a bass, it’s rare: most of the time, you’ll be playing single notes only. That’s because the bass is mainly used to underpin and outline the chords being played on guitar or keyboard instruments.

Bass Amps, Cabinets and Modelers

Basses create frequencies well below that of guitar, so you should avoid playing it through your regular guitar amp, especially at higher volumes. You don’t want to blow the speaker cone! (You can, however, play bass through a P.A. system (using a D.I. (Direct Inject) box) or powered monitor wedges.

Instead, you should opt for a dedicated bass amp. High-quality bass amps, pedals and preamps are all available from Ampeg, a company well-known for bass-oriented products. If you record at home, you can also use your audio interface for direct connection into your DAW. Many guitar modelers, including the Line 6 Helix, HX Stomp or Pod Go also allow for direct connection and offer numerous preset bass patches.

Providing Harmonic and Rhythmic Support

The bass player is expected to support both the rhythmic and harmonic structures of the song. The best way to do the latter is to play chord tones underneath the actual chords. You can opt to play static chord tones (i.e., those that stay on one note) or walking basslines that use scales to create more movement. Quite often, bass players will create riffs that form the basis of the song, or will double guitar or keyboard riffs to add extra depth and power. The approach you take comes down to your own sense of musicality, creativity and skill … much like playing guitar.

If you have a strong understanding of chord/scale relationships and chord-tone arpeggios, you’ll appreciate why using chord tones creates the strongest basslines, the same way that chord-tone melodies and solos sound stronger and more resolute when played on guitar.

In terms of underpinning the rhythmic aspects, the key here is to lock in with the bass (“kick”) drum. Do this, and the groove will feel tight, dynamic and powerful. That doesn’t mean you necessarily have to add a note every time the drummer plays the kick, but you should always be locked into your own pocket on top of those pulses. You may even want to work out those parts with your drummer in advance.

Make a point of listening carefully to the overall rhythmic and harmonic feel that the other instruments are adhering to. I always think the best basslines are the ones that you feel, but don’t necessarily hear as a focal point in the song. Simpler lines are often more effective than complex ones because they better allow the other instruments room to breathe and move above them.

Bass Playing Techniques

The first thing you’ll notice when transitioning from guitar to bass is how much bigger the neck and fretboard are on a bass; the strings are further apart too.

Don’t worry, though. As mentioned earlier in this posting, with a little practice, you’ll start to adapt to the new physicalities. Try to keep your fingertips facing the strings and fretboard, and navigate the wider shapes by pivoting and rocking sideways on your thumb.

Depending on how well your bass is set up, you may also need more hand strength to depress the strings to the fret wires. My advice is to not overdo it at any one practice session. Build up hand strength over time, and never strain your fingers, wrist, arm or shoulders.

As with guitar, you should hold the neck of the bass at a forty-five-degree angle from the body. (You can see this kind of positioning in the video below.) This allows for the wrist to remain straighter. When seated, you’ll want to place the bass on the leg farthest from the headstock.

You can of course play the bass with a pick, same as guitar (in fact, certain types of music, such as hard rock or metal, may even benefit from this), but many bassists prefer to pluck the strings with their fingers and/or thumb. Playing with a pick results in a more defined tone, but using your fingers gives the notes the classic “thump” that most listeners associate with bass. Bassists typically use their index and middle fingers to alternately pluck the strings. Some players rest their thumb on a finger rest or pickup, or on the string below the one they’re playing to stabilize their plucking hand.

I am, of course, primarily a guitarist, but when playing bass, I generally eschew using a pick. Instead, I fingerpick the notes, assigning the thumb to the low E string, index finger to the A string, middle finger to the D string and ring finger to the G string. Traditional and professional bassists would probably be horrified by my technique, but I find that it’s easier for me to articulate scales and arpeggios this way.

I adopted this technique because the tendons on my picking hand couldn’t sustain the repetition on the larger strings. Again, don’t overdo your practice sessions when getting used to this larger, more physically demanding instrument.

Getting Started

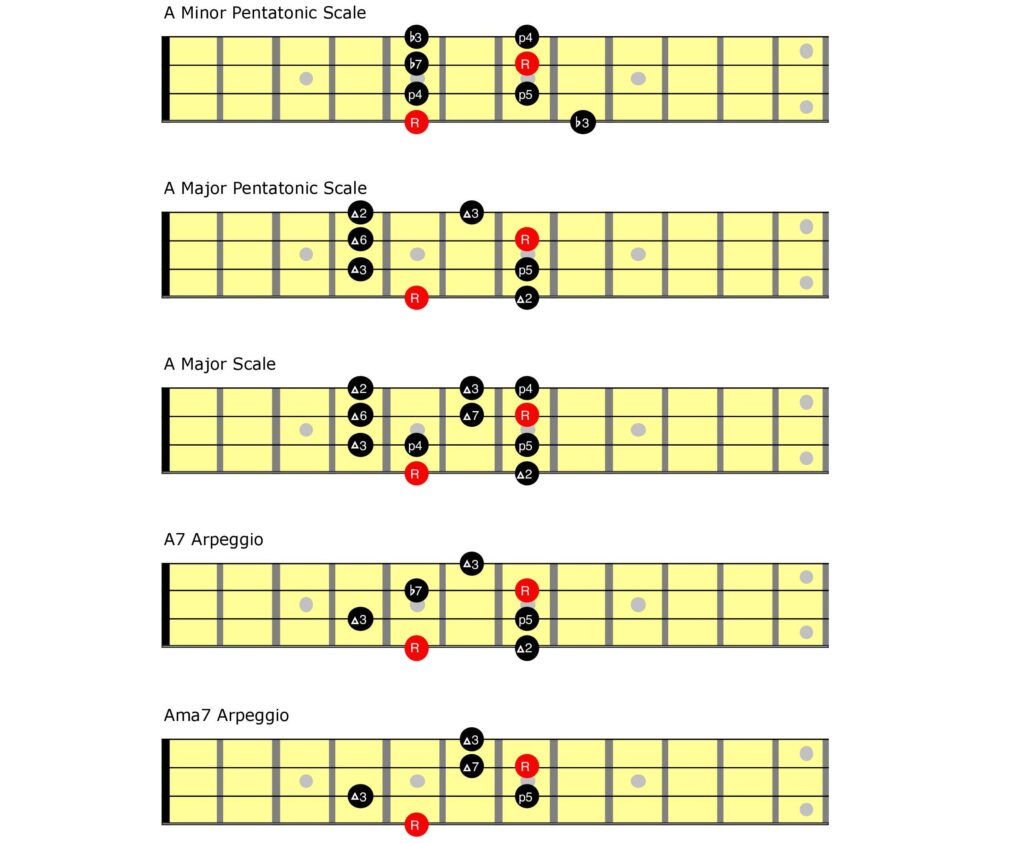

I think one of the best ways guitarists should begin adapting to bass is to simply play major and minor pentatonic lines. These will allow you to easily outline the tones in most chords. For example, the minor pentatonic scale is basically a minor 7th arpeggio with an added fourth, so minor chords are covered. The major pentatonic scale can be used to outline major and dominant chords since the five notes in that scale consist of a major triad plus the second and the sixth. The chart below shows how this works:

Of course, if you know major seventh and dominant seventh arpeggios too, you’ll be able to expand your lines further, but start by keeping it simple and try outlining a simple progression such as the one in the video below.

A Word About Slash Chords

You can, of course, also opt to use bass notes that aren’t found in a chord. In tablature or chord charts, these are indicated by chord names that have a slash mark. These are usually referred to as “slash” chords; the letter following the slash is the bass note. For example:

A/B = an A major triad with B (the second) in the bass

A/D = an A major triad with D (the fourth) in the bass

A/F# = an A major triad with F# (the sixth) in the bass

Changing the bass note of a chord can dramatically change how it sounds, and even its chord quality (that is, whether it’s major, minor, dominant, etc.). For example, A/B creates an B11 chord, A/D creates a Dma9 chord, and A/F# creates an F#mi7 chord.

The Video

This video demonstrates my technique for playing bass, and shows various ways you can use major and minor pentatonic scales to outline a chord progression as if they were chord-tone arpeggios. Here’s the chord progression used:

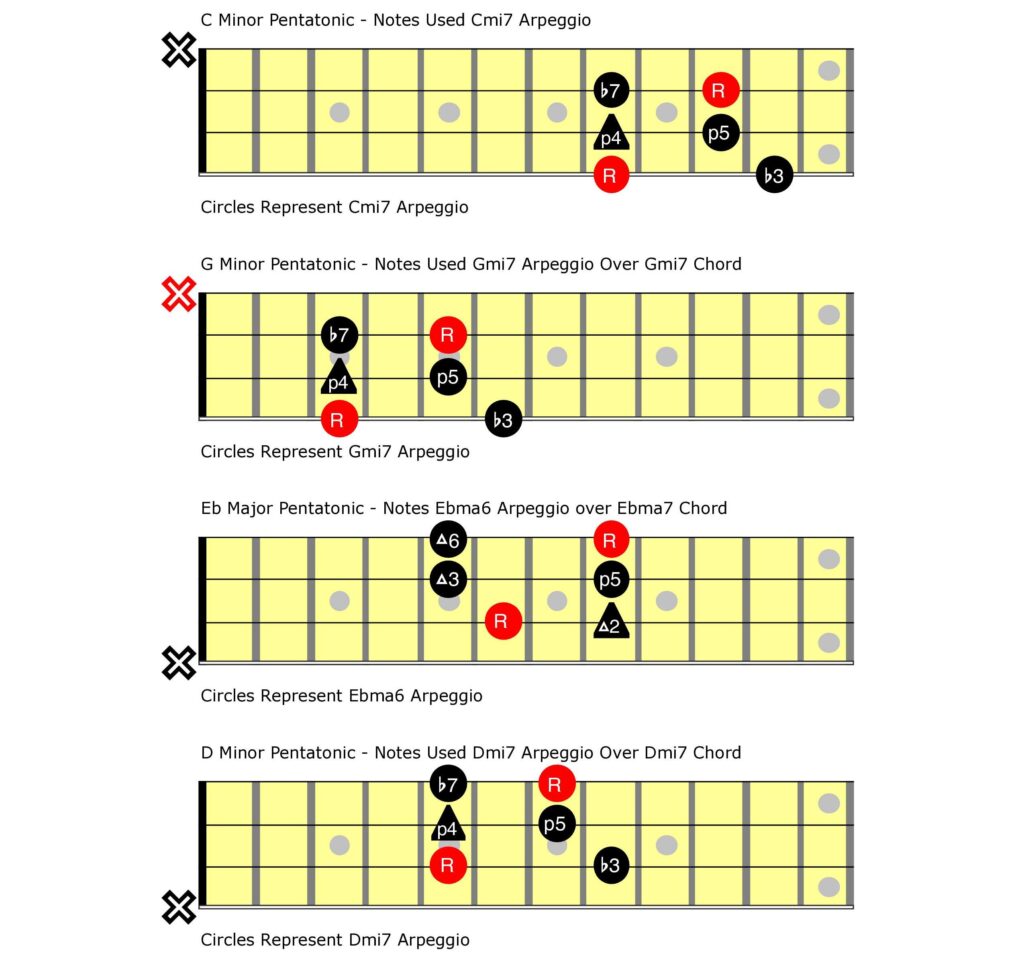

Cmi7 / Cmi7 / Gmi7 / Gmi7 / E♭ma7 / Dmi7 / Gmi7 / E♭ma7 / Dmi7

The fingerboard diagrams below show the scales and arpeggios I employed to underpin those chords. Try following along if you have a bass.

The Bass

Yamaha basses have long been used by many of the world’s finest session players and touring musicians. I’ve had a BB434 model in my studio for the past four years, and it plays like a dream, looks really cool on camera and always sits perfectly in the mix.

The six-bolt miter neck joint holds the neck of this bass closer and tighter to the body, acoustically fusing these two separate components into one. Compared to a conventional bolt-on joint, miter bolting offers a more efficient transfer of string vibration throughout the body. The end result is outstanding sustain and resonance that brings every note to life.

The resonant alder body pairs perfectly with the five-piece maple/mahogany neck and rosewood fingerboard. In addition, the BB434’s custom V5 Alnico magnet pickups are tuned to deliver a brighter sound that cuts through in live performance and requires minimal EQ when being recorded.

The Wrap-Up

It can take many months (or years!) to acquire even the basic skills when learning a new instrument. But because guitar scales, arpeggios and melodic sensibilities all translate well to bass, guitar players have the unique opportunity to transfer their existing knowledge to the bass for near-instant gratification and musical rewards.

With a little patience to make the necessary physical adjustments and acquire a full understanding of the musical applications of the instrument, you can enjoy a lifetime of pairing the low-end frequencies of the bass with your guitar.

Want to learn more about bass? Check out these postings by fellow Yamaha bloggers E. E. Bradman and Michael Gelfand.

PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR.

Click here for more information about Yamaha basses.