Berklee College of Music Teams Up with Steinberg

Film scoring students at this prestigious school are now using Cubase as their DAW software.

Berklee College of Music in Boston is one of the leading institutions for contemporary music education in the U.S. In addition to turning out highly proficient musicians and composers, it designs its curriculum to give its graduates the best shot at getting work in the competitive music industry. To that end, the school recently decided to begin using Steinberg Cubase as the digital audio workstation (DAW) software in its Film Scoring program.

Making the Decision

A change like this doesn’t happen overnight. It required a lot of advance discussion and planning, and began with the purchase of Cubase licenses for key members of the faculty who are involved with teaching film scoring. That allowed them to get familiar with the software before the fall semester, at which point incoming film scoring students all received their own copies of Cubase.

Following the Industry

So what made Berklee decide to make the switch? One reason is the feature set offered by Cubase, particularly in the MIDI editing area — something that’s of critical importance when it comes to composing for film. “It’s a great piece of software, a really powerful tool,” says Sean McMahon, who recently became chairperson of Berklee’s Film Scoring Department. “Cubase does a great job of getting out of the way and allowing a composer to be creative.”

But the primary impetus was the belief of the administration and faculty that Cubase represents the future in the very competitive area of film scoring. “We like to be a microcosm of the industry and model it closely [so we can] prepare our students for the reality of what they’re going to face,” McMahon explains.

Berklee took advantage of its alumni network, including those working as film composers, to take the temperature of the market. “We’ve done surveys of alumni,” McMahon says, “and the faculty are all practitioners. They’re industry professionals, so they’re plugged in as well.”

The Pathway In

The need to be fluent in the software that’s most popular with working pros is particularly crucial in the film composing world. “We think being compatible with your peers is really important,” McMahon explains.

In addition, the path to success in this field often involves starting as a composer’s assistant. Through internships and entry-level jobs, budding film scorers learn the ins and outs of the business and make invaluable contacts.

“It’s important that we prepare our students for these types of jobs,” McMahon says. “At first, composers don’t need assistants for their musical chops or compositional skills; they need them for their technical skills. So, if you want to get a job with a composer who’s a Cubase user and you [yourself] don’t use Cubase, odds are you’re just not going to get it.”

MIDI Orchestration Power

Most film composers initially write and arrange their scores in their studios, creating parts using sampled MIDI orchestral instruments. Much later in the process, these parts are replicated and replaced by real orchestral musicians. But during the initial writing phase — and when the composer is working with the director to refine the score — the instruments typically remain virtual.

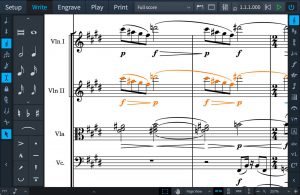

As a result, the ability to manipulate MIDI orchestrations is critical, and Cubase’s toolset for this is extremely powerful. McMahon provides an example: “It’s fascinating what you can do with articulations — something Cubase calls “Expression Mapping.” Let’s say you had a Violin 1 (first violin) line. If you were writing it on paper, you could indicate pizzicato, staccato, legato. There are all kinds of bowings and articulations you could use.”

“In the past,” he continues, “to manage the plethora of different articulations for a single track within a DAW, composers would need to use [tools that] were awkward and could be confusing in the orchestration process. But with Cubase’s Expression Mapping, the composer can instantaneously change articulations at the note level instead of writing them in as MIDI note data. That’s pretty sophisticated and has many benefits.”

Open the Dorico?

McMahon is also intrigued by the integration of Cubase and Steinberg’s Dorico music notation software. He sees this as being particularly helpful for converting MIDI scores into playable parts. “I’m an orchestrator by profession,” he points out. “Composers give me MIDI files, and I convert them into a coherent, comprehensible musical score for musicians, for human beings.”

It’s a complicated task, what with the different transpositions required for various orchestral instruments. But McMahon thinks Dorico has great potential for speeding up the process, and is currently considering it for possible future use within the film scoring curriculum.

But that’s for a later date. Right now, the emphasis is getting film scoring students up to speed on Cubase … and according to Bruce Bennett, Berklee’s Senior Director of Technology Services, there’s even a chance that Cubase’s role at Berklee could increase beyond the Film Scoring Department in the years ahead. “It’s such a good toolset for creativity — orchestral or otherwise — that it may organically grow with our students elsewhere at the institution,” he says. Stay tuned here for future developments!

Photograph by Cheryl Fleming.

Click here for more information about Steinberg Cubase.

Click here for more information about Steinberg Dorico.

Click here for more information about the Berklee College of Music.