The Sounds of Silence

When it comes to music, less can be more.

In a recent posting I touched on the wit and wisdom of jazz pianist Thelonious Monk, citing his profound and poetic definition of the word genius (“the one most like himself”).

This time around I’d like to take a closer look at another all-too-true Monk aphorism: “What you don’t play can be more important than what you do play.” A decade after Monk uttered these immortal words, Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen restated the theme when he reportedly instructed the group’s backing musicians to pay more attention to the space between the notes than the notes themselves.

Of course, for centuries beforehand, classical composers were, to great effect, employing the stark contrast between lots of notes and few (or none) of them. Some scholars say that it was Ludwig Von Beethoven who pioneered the method. His Eighth Symphony, for example, has been described as “compression and containment … the art of interruption and sudden spillover. Cadences stop, start and stop again; they play games with our sense of order.” From LVB’s masterpieces to the finale of Sibelius’ Symphony No. 5, with its huge closing chords and even huger gaps of silence, to Barber’s Adagio for Strings, with its long gasp of nothingness that presages the orchestra’s timid re-entry, the message is clear: Less can be more. (A concept taken to its absolute extreme with John Cage’s 4’33”, which consists of four minutes and 33 seconds of … absolutely nothing.)

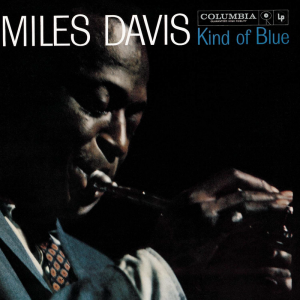

Probably the musician who best characterized this approach was the enigmatic jazz trumpeter Miles Davis, who early in his career developed an improvisational style that was based on the way Picasso used a canvas, where the focus was not on the objects themselves, but the space between them. As best-selling author (and fellow Yamaha blogger) Dr. Daniel J. Levitin has written, “Miles … described the most important part of his solos as the empty space between notes, the “air” that he placed between one note and the next. Knowing precisely when to hit the next note, and allowing the listener time to anticipate it, is a hallmark of Davis’ genius.” Nowhere is this more apparent than in Miles’ breakthrough 1959 album Kind of Blue, where his methodically disciplined phrasings are interspersed with long silences that are sometimes as long as the phrases themselves. Yet his solos on that album are nothing short of riveting, particularly in the way they contrast with the busier passages played by John Coltrane and Julian “Cannonball” Adderly — fellow jazz legends who acted as sidemen on this seminal recording, along with pianist/composer Bill Evans. Even if you don’t consider yourself a fan of jazz, you owe it to yourself to give this gorgeous, deeply meditative album a listen.

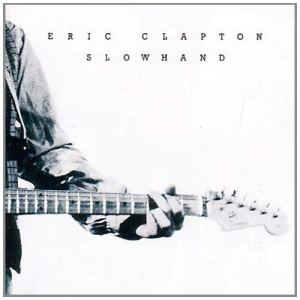

In the rock world, most soloists are, of course, guitar players, and they generally pride themselves on their ability to cram as many notes as possible into each moment. (As the old joke goes, “What’s the difference between a shredding guitarist and an Uzi? An Uzi can only repeat itself 10,000 times a second.”) One exception to that rule is Eric Clapton, who in his younger days was nicknamed “Slowhand” for the way he eschewed rapid-fire solos in favor of a more languid — but no less effective — approach. (Yes, he may have temporarily abandoned this tactic during his stint with ’60s supergroup Cream, but one could argue that his lead lines were often less dense than the bass underpinnings being woven by Jack Bruce.) For examples of how restraint can work better than bombast, check out Clapton’s lead work on his hit single “Wonderful Tonight” or his (uncredited) solo on The Beatles’ “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.”

But it isn’t just in terms of soloing that silence is key. It can be a powerful tool in musical arrangement, too. As an example, check out “All Right Now,” a 1970 hit for the English rock group Free. The way the verses jump out at you is not only due to the stripped-down instrumentation accompanying Paul Rodger’s vocal (just drums and one solitary guitar — not even bass) but because of the long gaps between the guitar chords, populated with just a hint of percussion. When the choruses and solos kick in with fuller instrumentation (including bass), the contrast is an attention-grabber.

Speaking of bass, the best four- and five-string players know the importance of leaving space for the vocals and melodic instruments. Session bassist Chuck Rainey is perhaps the perfect example, renowned for a spare approach that supports but never detracts from the central melodic content. No coincidence, then, that Rainey appeared frequently on Steely Dan recordings, having clearly won the approval of the aforesaid Donald Fagen.

Mozart was once asked what the greatest effect in music was, and his reply was, “No music.” Pithy, yes, but something worth keeping in mind the next time you begin crafting a song or musical arrangement … or the moment you step into the spotlight to take a solo.