Marching through Time

A brief look at the history of marching bands.

Marching bands are ingrained in our culture. You see them regularly at football games, school and college events, parades, military ceremonies and in organized competitions against each other. But how did they originate? In this article, we’ll take a closer look.

Two Varieties

Today in the United States, marching bands fall into two broad categories. One, referred to simply as “marching bands,” is what you’re likely to find at high schools, colleges, the military and in the competitive Bands of America program, which culminates annually in the BOA Grand National, Regional and Super Regional Championships.

The other is the drum and bugle corps (aka “drum corps”). Since 1972, this has mainly manifested itself in an organization called Drum Corps International (DCI), which has an extensive roster of corps nationwide and similarly holds annual championships every year.

Ancient Origins

The juxtaposition of musical instruments and the military goes back to ancient times. Armies used percussion and woodwind instruments as signaling devices that could cut through the din of a battlefield and transmit basic commands to soldiers.

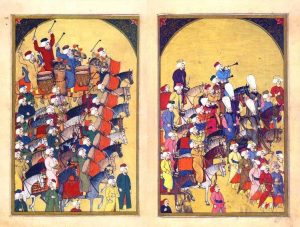

The earliest military marching bands that historians have documented were from the Ottoman Empire in the 13th century. The Ottomans conquered vast swaths of territory in Northern Africa, the Middle East and southern Europe and brought their marching band tradition with them.

In the centuries that followed, the concept of military marching bands spread into northern Europe and eventually made its way to the new world.

Revolutionary Ensembles

In the 1700s, military marching bands appeared in Revolutionary-era America in the form of fife and drum corps. Fifes are high-pitched wind instruments whose piercing tones are audible at a great distance. The drummers in these corps used rope-tension drums, which were large compared to contemporary marching drums.

Fife and drum corps usually consisted of just a handful of musicians — often teenagers too young to fight — and provided not only battlefield communication, but music for drills and for when soldiers were on the march.

By the time of the American Civil War, fife and drum corps added the bugle as an additional melodic instrument. In addition, the rope-tension drums of that era were smaller, making them easier to march with at faster tempos. In those days, tempos ranged between 92 and 110 bpm.

Paging Mr. Sousa

Thanks in large part to famed composer and conductor John Phillip Sousa, marching band music expanded in terms of repertoire and instrumentation towards the end of the 1800s. Sousa wrote many iconic marches, including “Semper Fidelis,” the Marine Corps’ official song. He’s also credited with inventing the Sousaphone, a variant of the tuba, but with a wider bell, and a body shape that’s easier to march with.

Sousa conducted such ensembles as the Marine Band, the President’s Own Band — which played at presidential inaugurations and other state occasions — and later his civilian marching band, the Sousa Band. During Sousa’s era, marching tempos got faster. A good example is his iconic composition, “Stars and Stripes Forever,” which features a 120 bpm tempo.

Into the 20th Century

Around a hundred years ago, competitive drum corps were born in the form of programs sponsored by the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars® (VFW). The first such corps, called the Senior Corps, was open to any age so that World War I veterans could participate. Later, in the 1930s, Junior Corps were formed, which had a maximum age of 21. “From after World War I until the mid to late 1960s, drum corps didn’t change very much,” says Dennis DeLucia, the color commentator for DCI broadcasts and one of the first musicians elected to the DCI Hall of Fame.

Loosening Up

By around the late 1960s, many who were arranging the music and designing the shows for drum and bugle corps were starting to become frustrated by the restrictions of key, instrumentation and tempo in the drum corps world. “Under the rules of the American Legion and VFW, you could only play what you could carry,” explains DeLucia. “Mallet percussion instruments were banned prior to the formation of DCI.”

But things were beginning to change. “Starting in 1974,” says DeLucia, “DCI allowed you to use one marching xylophone and one set of marching bells. In 1978, they allowed a marching marimba and a marching vibraphone.”

In the early ’80s, DCI made a rule change that ushered in the era of pit percussion. This allowed corps to supplement their marching instrumentation with a group of stationary musicians, called the “front ensemble.” Initially, the so-called “pit” was limited to large percussion instruments that couldn’t be carried while marching, but amplification was legalized in 2004, opening the gates to instruments that needed to be miked to be loud enough, such as marimbas. Electric guitars, electric and upright basses, and other “rhythm section” instruments were also approved at that time, followed in 2009 by electronic instruments such as synthesizers.

Enter Yamaha

Yamaha became a force in the marching band market in the United States in the 1980s. One of the reasons was the company’s “air-seal system” for drum construction. It offered superior consistency for making drum shells perfectly round — important for the drums to be easy to tune and to keep their tuning. For school band directors, those were critical attributes.

Another milestone occurred in the late 1980s, when bands and drum corps started to adopt a new type of snare drum head made of Kevlar or other types of laminated fabric — an innovation that also allowed the snares to be tuned much higher. However, these heads put more stress on the drums themselves, causing issues with breakage. In response, Yamaha was one of the leaders in developing a new drum design that could handle the higher-tension heads.

The company also made a considerable effort to find out what marching musicians needed out of their gear and developing products to match those needs — an initiative that continues to this very day. “They would bring some of their leading marching artists to the factory for two or three days at a time and literally work on shell depths for the tenor drums,” DeLucia says. “Does a 6″ tenor shell work better than a 6 1/2″ shell? What’s the best head configuration? All of those kinds of things were developed with useful input from the best marching instructors and players.”

In 1992, Yamaha became the first drum manufacturer to release drums in a variety of colors. Now, bands and corps had the option to purchase drums that matched the color of their uniforms. With the increased importance of the show aspects of marching music, particularly during competitive events, the ability to color-coordinate the instruments with uniforms was, and is, extremely important.

Want to learn more? Check out these related blog postings:

History of Drum Corps and Yamaha

Madison Scouts and Yamaha — Marching Together Since 1985

Preparing for a Drum Corps International Audition

Nine Things To Know Before Buying a Drumline

Click here for more information about Yamaha marching instruments.