Going for the Rare Notes

You don’t have to be a chop-buster to be a heartbreaker.

I was just 14 when I discovered what I would end up doing for the rest of my life. And ever since catching my first break, I’ve been in demand as a session player. To me, that qualifies as being blessed.

I’ve literally been playing bass for a living almost every day for more than four decades. I can’t count all the studios I’ve been in, or the live concerts I’ve played. I’ve never stopped to think about what it is that makes people call me for gigs, but maybe it’s my focus on constantly keeping the highest standards for myself. It’s not just about setting standards for playing, either — it’s personal, spiritual, physical, mental and musical, and that includes walking into a studio with an upbeat attitude and good energy.

When I was growing up, there were so many great examples of bassists setting the bar high: Jaco Pastorius, Stanley Clarke, James Jamerson, Paul McCartney, Verdine White, Rocco Prestia, Ron Carter, Ray Brown, Anthony Jackson and so many others. I was in awe of how talented they all were, and I wanted to be in their club. Through their playing, they taught me to make every note count, to play something memorable. That was my focus, because doing it meant that maybe one day I might be worthy of being thought of by others in that same company.

Wes Montgomery is still one of my favorite artists of all time because of his choice notes, and the ease with which he played them. He just got to me right from the beginning. His note choices and his use of space — everything about what he did was consummate, and that’s what defines an artist to me.

It definitely affected how I play. My philosophy is more about which notes than numbers of notes. And I like to go for the rare notes. Harmonically, my approach is to figure out the most obvious, simplest, lowest common denominator note, and then I move on to figuring out what substitutions I can come up with. Maybe it’s the third, or the fifth, but whatever choice you make shades the music and gives it a complexion. Once I know the root and chord, I figure out what notes are available to me that will make someone go “ooh.”

It’s all about listening. Rhythmically, I stay conscious of what’s going on with the drums. Lots of drummers I’ve played with say, “When I put that kick drum down, there you are.” That’s because I’m listening.

I have the benefit of having had a musical education and background, but even with all of that, I’m still trying to let the music play me. It’s more of a spiritual approach than an academic one, though I ultimately draw on both. I listen, and then try to let the music tell me what it wants to hear. So it’s from the head, but much more from the heart.

With my background, I can technically play just about anything, but I usually choose instincts and spirit over virtuosity: things that move me emotionally. You don’t have to be a chop-buster to be a heartbreaker. There are some musicians who can’t read a note of music, but when you hear them play, you can tell it’s them. You hear their personality.

A good way for me to keep perspective is to think back to my early days, when I was fortunate enough to get my start with Barry White, playing on all his records back in the late ’70s. His way of putting a hit together meant giving everyone their part, and in those sessions, he had two bassists. He gave me what seemed like a simple part where I waited and played a sliding note; he gave the other player a part that required him to wait, and then play a snap. With him, all you did while recording was listen closely and play that one part, but what you ended up with was an amazingly structured bass foundation.

Those were the sessions where I met guitarists Ray Parker Jr., Melvin Ragin (aka Wah-Wah Watson) and Lee Ritenour, as well as drummers Ed Green and Gene Page, who arranged those records. They were the top guys, and when they heard me, they referred me to other gigs. Then, in the early ’80s, I got introduced to pianists Patrice Rushen and Bobby Lyle by flutist/saxophonist Hubert Laws, and they started going out and recommending me for jazz gigs.

Soon after that, I met Phil Collins and Eric Clapton, which opened up the rock-and-roll side of my playing. I also played on Anita Baker’s records, whose music wasn’t just four-chord pop hits — it was sophisticated and song-based, and that gave me a chance to be heard in the R&B world.

Every day I’m thankful for the path that music has led me down, and the blessed life it’s given me. I used to dream about playing with all kinds of great musicians, and it happened, and it just keeps happening. It’s all been too much fun!

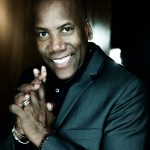

Photographs by Kharen Hill.

For more information, go to nathaneast.com.

Click here to learn more about the Yamaha BBNE2 Nathan East Signature Bass.