Tagged Under:

How to Transpose

Especially when working with singers, you’ll need this important skill.

As a keyboardist, you will likely be called upon to accompany a vocalist on occasion. However, there will probably be times when the song they choose will not fit their vocal range if played in the original key (i.e., the one used in the recording).

Perhaps some of the highest (or lowest) notes are just a bit out of their range, or maybe a female singer wants to perform a song originally written for by a male singer, or vice versa. If they are having trouble hitting higher notes, you’ll want to move the key down. If the song travels very near or even below the lower end of their range, you’ll want to move it up. Either way, to help them sound their best, you’ll need to change the key — a process called transposing.

On a digital keyboard or piano, transposition is easy: all you have to do is press a button (usually labeled “Transpose”). After you set the amount up or down by the desired number of semitones, you simply keep playing in the written key, and the instrument will do the rest for you. (This video covers the basics.) Just be sure to reset the transposition value back to 0 when you’re done playing the song!

On acoustic piano, however, the process is quite a bit more challenging. Here are some helpful tips on how to do it.

The Importance of Rehearsal

Often, you and/or the singer won’t know there’s a need to transpose until you do your first run-through of the song during rehearsal. (Yes, you absolutely should get together and rehearse before the performance!) During the run-through, listen for issues like notes out of the singer’s range, and whether the timbre (tonal quality) of their voice changes unpleasantly when they hit certain notes. Be sure to play the whole song, not just the beginning: often it’s in the middle of a tune that the melody changes more.

Bear in mind that when you support a vocalist, you shouldn’t be playing the song directly from the sheet music (if you have it on hand), as you don’t want to be playing the melody — that’s the singer’s job! So you are only concerned with the chords, and perhaps some signature melodic phrases that may occur in the intro, etc. (I am assuming that you know how to play chords and have some understanding of harmony. For a refresher, I’ve covered the subject in this blog and this one.)

If you are working with an experienced vocalist, they may already know what key they prefer to sing the song in. Even better, they might have a chord chart for you to use — it’s always good to ask in advance.

The “Brute Force” Method

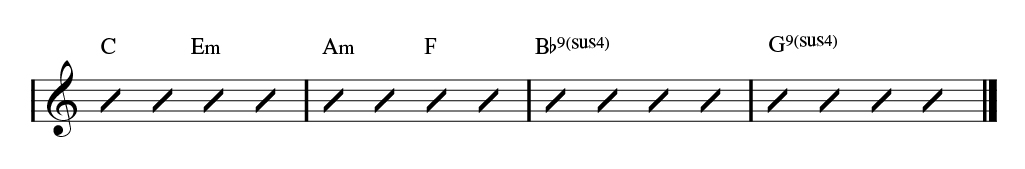

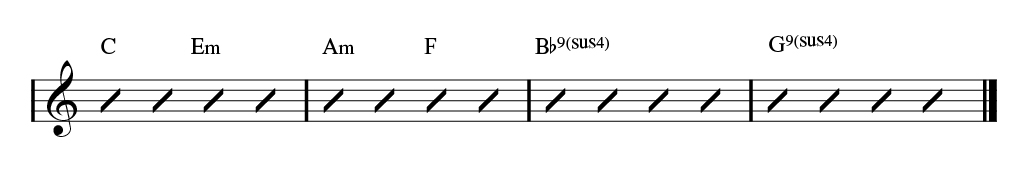

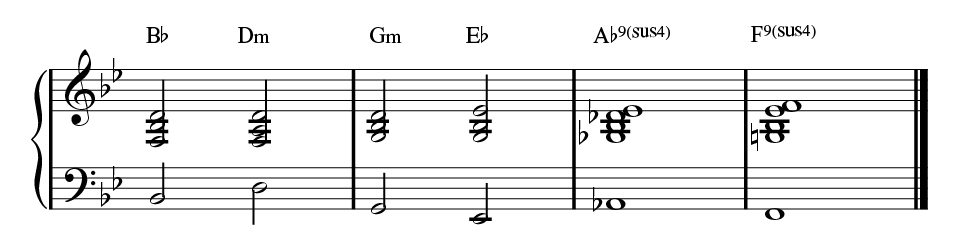

This is a good way to approach changing the key of a song when you have the sheet music or chord chart to work from. Here’s an example of what a chord chart of a simple pop tune chord progression might look like:

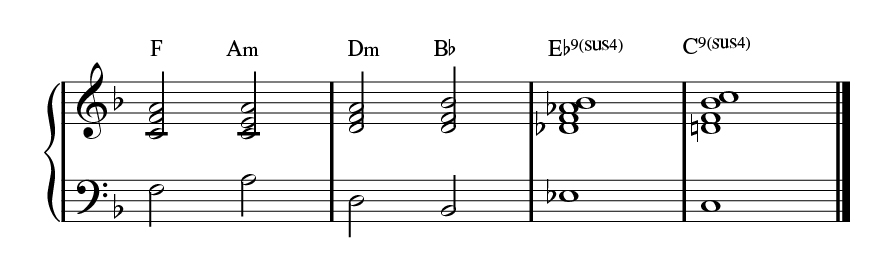

And here’s how I might opt to play those chords:

If the singer and I come to the realization that the key needs to change, the first decision is: How far off is it? If they can get through the piece okay but a few high notes are hard to hit, then you can transpose it down by a small amount. If the whole song feels uncomfortable, you’ll need to move it to a key further away. To do this, you need to be familiar with the concept of intervals between notes. These are expressed in terms like a half step, a whole step, a major third, a perfect fourth, etc. My two-part “Playing By Ear” blog will help you review the concept.

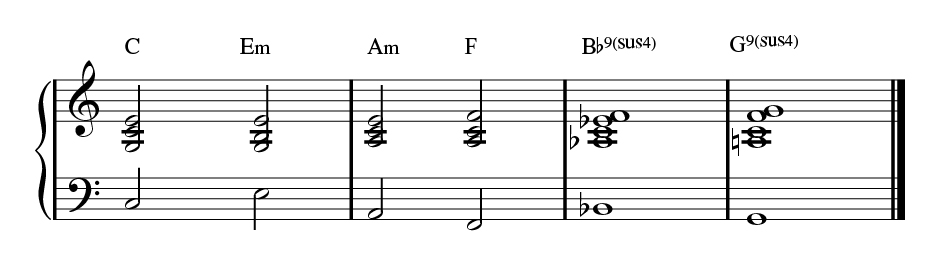

Let’s say you only need to lower the key of the song by a whole step (two half-steps). As you look at each chord on the chart, simply think of the note that is a whole step lower than what’s on the page. In the chart shown above, the first chord is a C major triad. So you need to think and play a B-flat major triad instead. The second chord is an E minor, so play D minor instead … and keep doing this all throughout the tune. If it’s hard for you to do this in your head, get a pencil and write in the replacement chords you need to use. Here’s that chord progression, modified to play a whole step lower:

And here’s how I might play these chords:

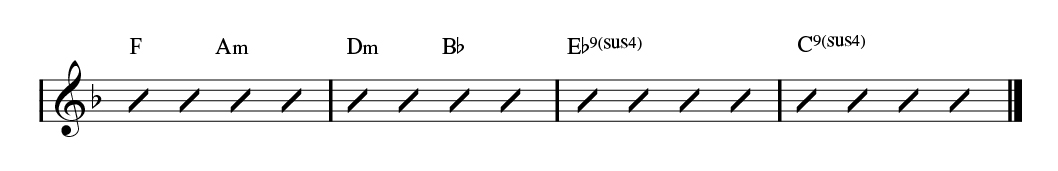

Let’s try the same concept, but now we’ll bring the tune up a perfect fourth, so instead of starting on C Major, we’ll start on F Major:

I’d likely voice the chords like this:

It may take you some time to get comfortable with doing transpositions this way, but it will become natural the more you practice it.

The Numbering Method

Most music is set in a given key, which means it is based on the notes of a scale, be it major or minor. At the start of the first line of the sheet music or chord chart, you’ll find a number of sharps or flats; these tell you which notes are to be played on the black keys instead of the white keys. This is called the key signature. If you already understand this concept, and you know your major and minor scales, you can use that knowledge to help transpose songs.

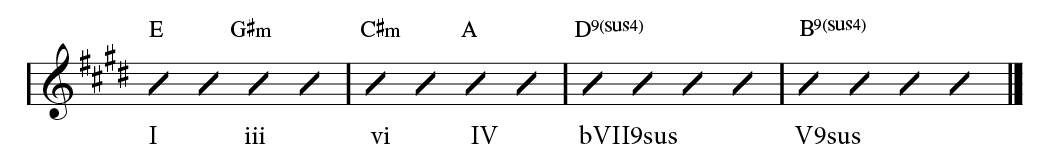

To show you how this works, let’s return to our original example, which is in the key of C major, with no sharps or flats:

(Yes, I know there is a B♭9sus4 chord in the third bar — I’ll deal with that in a moment.)

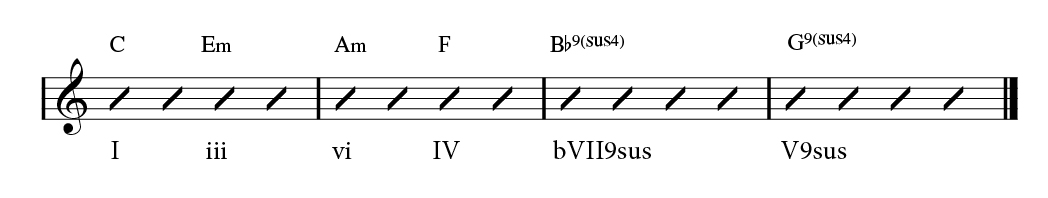

Roman numerals are commonly used to denote the relationship of a chord to the key center, with a “I” indicating the root chord, “V” indicating the chord built on the fifth step of the scale, etc. Uppercase numerals are used to designate major triad-based chords, while lowercase are used for minor or diminished-based chords.

Here’s how the chart above would be numbered:

The great thing about using numbers this way is that the chord progression becomes “universal” — it can be applied to any key. That’s why this is the most common way that musicians communicate with each other about tunes and chord progressions.

As you can see, the chords in the first two bars are from the key of C Major, but in bar three, the B-flat root tone occurs outside of the C Major scale. That’s no problem; instead of vii, it’s called a flat vii (♭VII), using the uppercase roman numeral with the 9sus characters to denote that it is a Dominant ninth chord that has a suspended fourth in place of the usual third. In this fashion, any chord can be described relative to the key center and assumed scale.

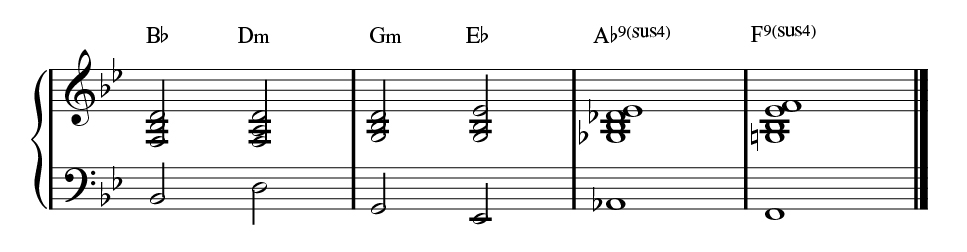

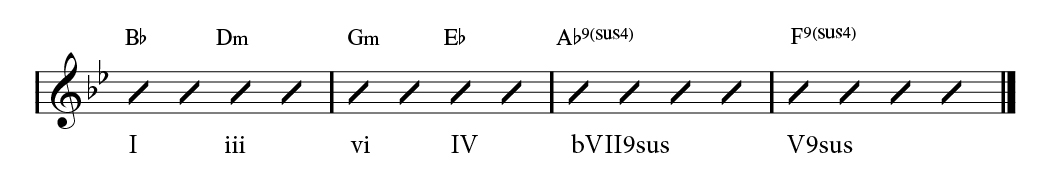

Best of all, when it comes time to transpose, all you have to do is think of the new key signature/scale, keeping the roman numerals intact. For example, if we wanted to lower this chord progression by a full tone, the chart would look like this:

Again, the chords might be played like this:

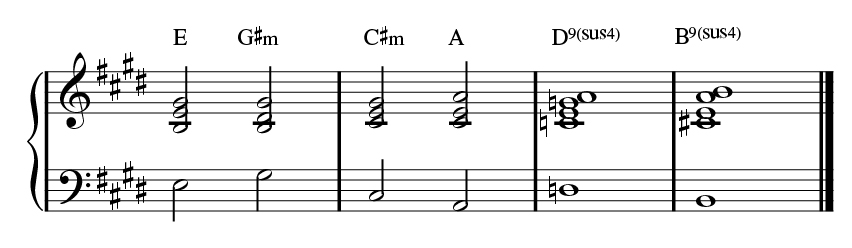

As another example, let’s say we need to raise the song to the key of E Major. Here are the transposed results and the possible voicings:

Make it part of your practice routine to take songs you know and play them in other keys. Work on your knowledge of and comfort level with intervals, as these will allow you transpose in your head quickly and easily. You can even sharpen your transposition skills when away from the keyboard — just look at some music and think through the chords in different keys.

All audio played on a Yamaha P-515.

Check out our other Well-Rounded Keyboardist postings.

Click here for more information about Yamaha keyboard instruments.