Tagged Under:

Playing By Ear, Part 1

How to learn songs by listening to them.

There are plenty of musicians who don’t read music. Instead, they are able to quickly pick up songs by listening to them. The Beatles are a good example. They showed each other their new tunes by simply playing them repeatedly, and it seems to have worked out pretty well for them!

There are also several well-known jazz musicians who only played by ear, including pianist Erroll Garner and guitarist Wes Montgomery, to name just two. Mind you, I’m not trying to make a case for not learning to read music — I think it’s an essential skill for all musicians. But I also feel that learning to play by ear is an equally important, if not more important aspect of musicianship to develop, regardless of how well you can read.

The good news is that playing by ear is a skill that can be learned, with an analytical approach and a lot of practice. In this two-part series, I’ll show you how.

Mastering the Melody

Start by listening to the song over and over until it becomes familiar to you. As you do so, try to sing along with the melody. It doesn’t matter how well you sing; this is a great first step before you even touch your keyboard. After you get comfortable with the song, focus on just the first note. After listening to it a few times, stop playback at exactly that moment so that the sound of that note “hangs” in the air. Now try singing it. When you feel you’re correctly singing that first note, try to find it on your keyboard. There are only 12 different notes in Western music, so it shouldn’t be too hard! If you’re having difficulty finding that first note on your keyboard, try to analyze why. Is the note you’re singing higher, or lower than the note you’re playing? Does it seem close, or far away? Thinking about what you’re hearing is a much better approach than just randomly poking away at notes.

Once you’ve found the opening note, you are on your way to picking out the rest of the first melodic phrase. The overall approach is similar — again, singing the part can be helpful — but try to hear the melody line in these terms: Does the melody move up, or down, and when does that change? Does it move through notes that are close to one another, or does it seem to jump further afield? These two aspects (direction and distance) will help guide you throughout the process. Once you’ve figured out the direction in which it moves, you can look for which note it moves to. This is achieved through a technique commonly known as ear training (actually, it’s training your brain, but we won’t quibble over semantics).

Ear training is all about learning to recognize melodic intervals — that is, the distance between two notes. One of the best ways to accomplish this is to use familiar songs to associate with each of these distances/intervals. This will help you to quickly hear (and therefore find) the notes in a melodic phrase.

In music theory, intervals are described by the number of half-steps (i.e., semitones) each note is from the preceding note. Here’s a list of some of the most common musical associations used, along with audio clips to demonstrate how they sound:

– Because it’s the smallest interval possible on the piano, the first is the half step/minor 2nd. The iconic cue in the movie “Jaws” that signalled that a shark was nearby works well to demonstrate this:

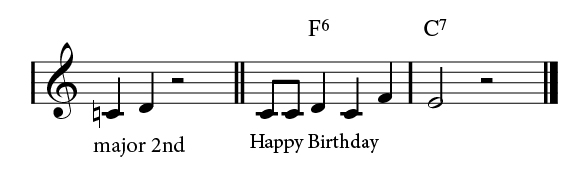

– The whole step/major 2nd (2 semitones away) has many possible references: “Happy Birthday” is probably the most well-known:

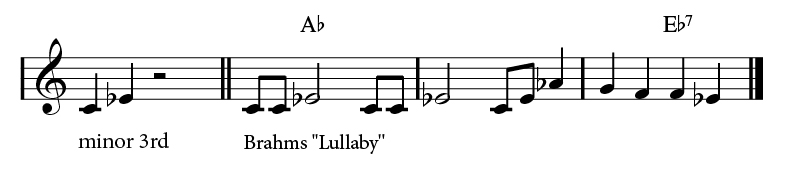

– The minor 3rd is 3 semi-tones away and is famous as being the lead-in to a lullaby:

– The major 3rd is four semi-tones away, and should be very familiar as part of the sound of a major triad:

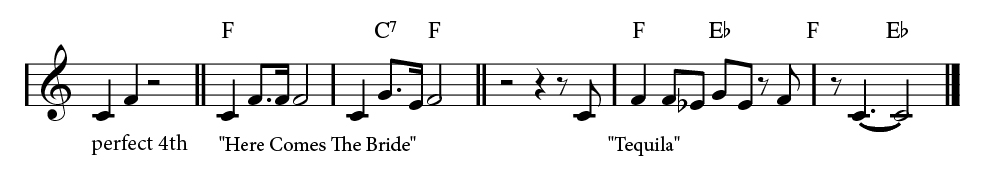

– The interval called a perfect 4th is five semitones away and will be instantly familiar to anyone who’s ever attended a wedding:

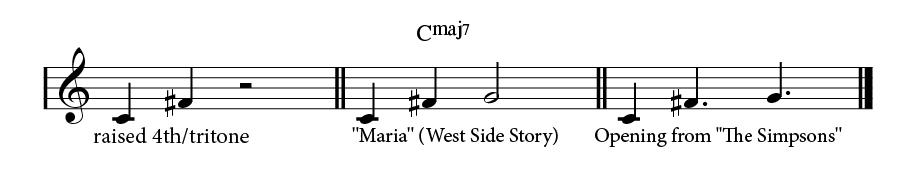

– The next larger interval is the raised 4th (also called a tritone), which is 6 semitones away:

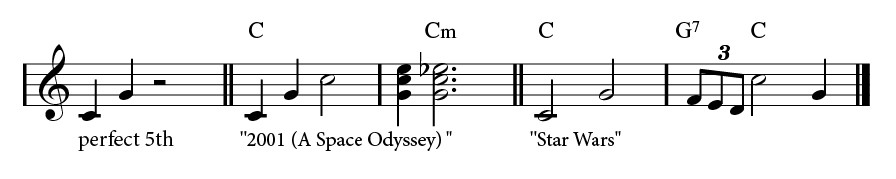

– You’ll find a perfect 5th located 7 semitones away—an interval that will be recognizable to fans of sci-fi movies everywhere:

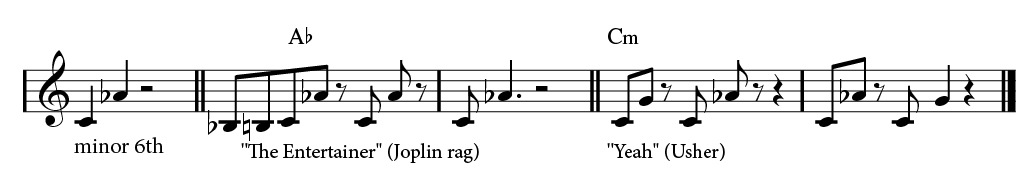

– The minor 6th is 8 semitones away:

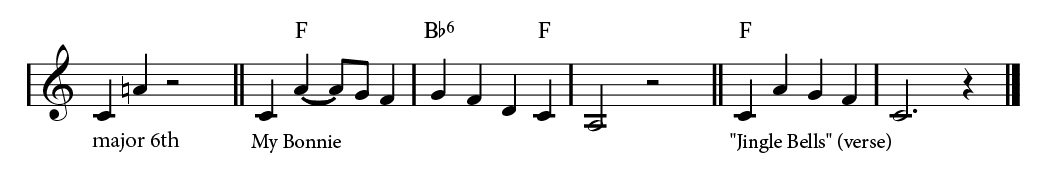

– … and the major 6th is 9 semitones away and is used in two iconic melodies:

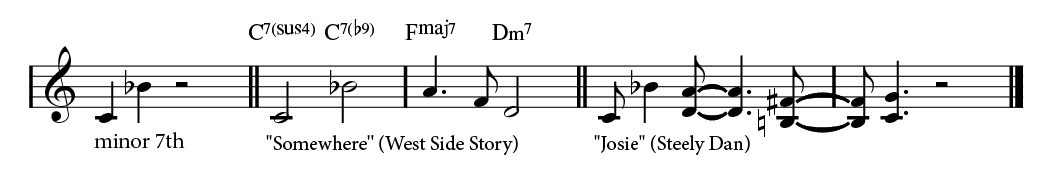

– Next up is the minor 7th, which is 10 semitones away:

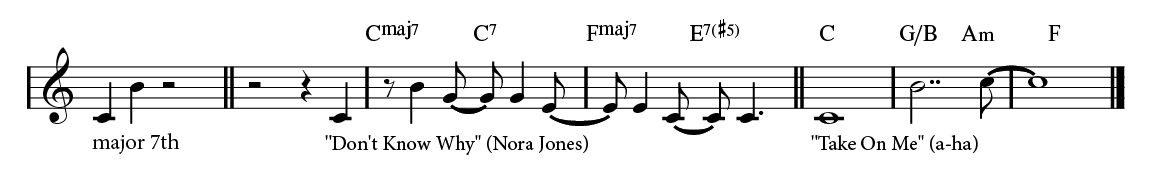

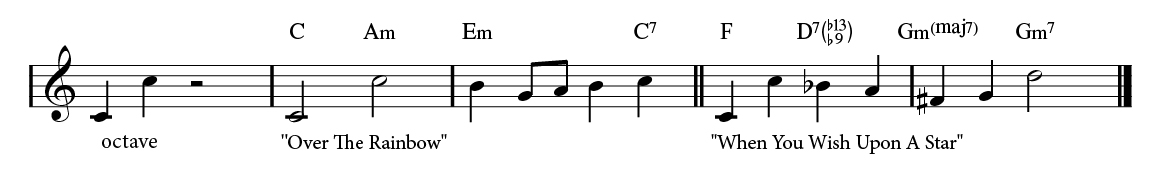

– The major seventh is 11 semitones away:

– And the last interval you need to train your ear/brain to recognize is the octave, which goes from one note to the next instance of that same note, 12 semitones away:

Whew! And we’re not done: You should also study these intervals moving downward as well as upward. Same principle — find a song to associate with each movement to get it in your ear and brain. If the above references don’t work for you, find your own (click here for some YouTube suggestions). It doesn’t matter what the actual song reference is — what’s important is that it is familiar to you and helps you to quickly recognize these interval jumps.

You can even turn ear training into a two-person game: One person plays a note on the keyboard, announces what it is, and then plays a second note; the other person guesses what the interval and second note is. There are also many online ear training exercises that can help you work on your pitch and interval recognition.

In Part 2, we’ll talk about using technology to learn both the notes and the chords to a song.

All audio played on a Yamaha P-515.

Check out our other Well-Rounded Keyboardist postings.

Click here for more information about Yamaha keyboard instruments.