Tagged Under:

When Freshmen Come in Behind

Instead of complaining about students being behind, adjust your expectations, refocus and teach the kids who are in front of you.

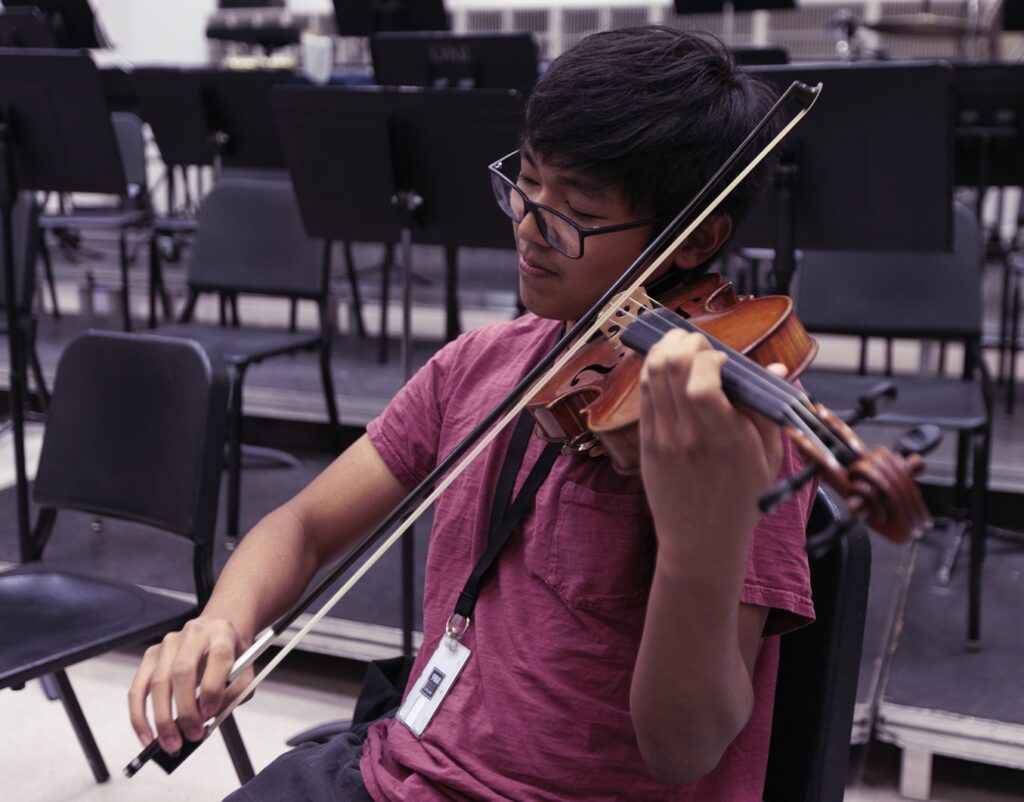

It’s August. You hand out a Grade 3 concert band piece to sight-read, and by measure four, you realize something’s off. Some of your students are counting like it’s their first day in band — wait, scratch that. They’re not actually counting. They’re ignoring the key signature like it personally offended them. Hold on — some actually don’t know what a key signature is.

Some students are holding their instruments like they’ve never even seen them before. You start to panic and ask yourself, What happened at the middle school?!

By the end of the week, you know some of the answers — the feeder music teacher was laid off, the long-term sub showed YouTube videos, half the instruments were broken, schedules were shuffled until October. The damage is real, and now it’s yours to fix. So now it’s time to ask for help.

This Isn’t Your Failure Even If It Feels Like It

When your high school ensemble sounds rough at the start of the year, it’s tempting to take it personally. I still do this even after 20 years of teaching. I live by a motto of “an ensemble is a direct reflection of its director,” but this isn’t quite true especially in August or September.

Freshmen who couldn’t play a concert B♭ scale or name the lines on the staff — these were kids who tried. They just didn’t get the reps. It wasn’t because their middle school teacher didn’t care. It was because that teacher left in February and the school ran out of subs.

One year, I had a saxophone player who literally didn’t know how to use the octave key. Not like, they forgot to press it — they didn’t know it existed! Another had never played with a tuner. When I asked about tuning procedure, she looked confused and said, “Oh, we just kind of started playing.”

We all want to fix it, make it better, prove that what we’re doing works. Instead of playing the blame game or wishing for something better, just diagnose what actually happened. Adjust and don’t absorb every gap like it’s your fault. Your job is to teach the students who are in front of you.

Sometimes the issue isn’t musical. I’ve had students come in with big gaps, but they also were dealing with huge personal stuff — housing instability, chronic absences, burnout. A student who missed 40% of last year is not going to have solid rhythm reading. That doesn’t mean you failed them. That means something much bigger failed them. But they’re still showing up. So, now we teach.

The System Is Bigger Than You, So Stop Carrying It Alone

There’s a difference between being a team player and trying to carry the entirety of music education on your back. Often, music teachers try to solve everything: scheduling errors, feeder program issues, attendance issues in the school. We think we’re being dedicated, but we’re just exhausting ourselves and not being particularly effective at solving these problems.

The lesson: Just because you can doesn’t mean you should.

One year, I decided to visit all nine of my feeder schools by mid-September. That meant hauling instruments, rearranging my prep periods, skipping lunch and getting home late — all for 12-minute mini-rehearsals with groups of students I couldn’t officially teach. I wanted to show support.

You can’t fix a feeder teacher quitting. You can’t make a program adjust their standards to fit yours. However, you can create a tighter recruitment process and check in regularly with the ones who stay. You can’t fix the counseling office’s scheduling software, but you can start emailing about enrollment in January instead of May. Starting earlier and getting your message to the kids before they are inundated with all other communication can be very effective.

Start mapping out the system around you — the one your kids go through before they land in your room — and then look for the one or two points of influence you actually have. That’s where you put your energy. Everything else? Name it. Write it down. Then let it go. (And yes, “letting it go” sometimes means complaining about it in the office while typing up your recruitment plan. This doesn’t mean you don’t care — this simply means you are caring where you are most effective.)

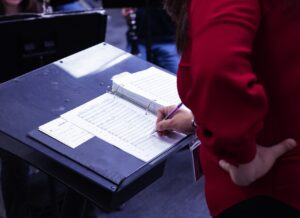

Document Everything and Adjust Expectations

If a kid shows up without a working trumpet for three months, that matters. If 20 students from one feeder didn’t get music classes in middle school, that matters. These aren’t excuses — they’re data. And although we are artists that are often brilliant at describing our feelings and emotions, data points are what really make change happen.

Consider a short running log on your computer. Just bullet points like:

- 6 students placed in choir by mistake, fixed in Week 2

- Feeder A: No 7th grade band last year

- 2 students switched to new instruments without teacher input

- 3 clarinets with cracked joints, replaced Week 4

It takes five minutes a week, and it’s been incredibly helpful when I get observed or when I need to advocate for additional support — which usually means money, but it sometimes means scheduling.

One time, I pushed for new mouthpieces — and actually received them! — just by showing that nearly a third of my brass players were using accessories that didn’t fit them or function. Without my notes, it would’ve just been me “complaining.” The log gave it context and urgency. (It also helped when I told the administration that a rival school had these mouthpieces and we didn’t.)

More importantly, it helps me tune expectations. If I walk into a year knowing that 40% of my kids lost a full year of instruction, I don’t plan like they’ve had a perfect handoff from middle school. I plan for who the kids are and what music education they actually received. That might mean spending a week on a single line of an exercise. Or swapping a concert piece because it turns out only two kids can play in 6/8. I don’t love doing it, but I’d rather underprogram and overperform than the opposite.

This isn’t “lowering the bar.” It’s focusing on growth.

Letting Go Isn’t Giving Up — It’s How You Make It to May

Somewhere along the way, a lot of us learned that “good teachers” hold everything together no matter what. This isn’t true because you can’t be the sole fixer of an imperfect system — you’ll break yourself first.

Letting go of that responsibility doesn’t mean you’re giving up. It means you’re teaching within the system, not in spite of it.

There’s a kind of clarity that comes from stopping the blame spiral — and I don’t mean to simply stop blaming others. I mean blaming yourself for the off-pitch horns, the flatlined recruitment, the burnout. For everything you can’t control but still feel responsible for.

You’re allowed to be frustrated and feel like this shouldn’t be your problem — because honestly, it shouldn’t. But when you actually let go of the guilt, you can use your energy to help the kids in your room.

You’ll sometimes catch yourself — “If I just worked harder!” will loop in your head. You could always come in earlier, stay later, smile more, be more stern, hand out more snacks, do less playing tests, maybe do more playing tests and improve your soldering skills so you can save a few bucks on brass repair bills. But after a month or two of working “harder,” you’ll need to take more days off just to recoup from the job. That’s a cycle you want to avoid.

Show up and teach well but guard your energy like your job depends on it — because it does.

One Last Thing

Every year, there’s a moment when you sit down and realize just how much your students didn’t get before they walked into your room. It’s heartbreaking. It’s not your fault, but it is your responsibility — just not in the way you think.

Ask for help. Address what you have the power to address and set clear goals and expectations for the real students in your room. If you need a minute to feel mad about it? Take it. Then pick up the baton and start where they are.