Improve Students’ Tone

Help strings and winds students break down the factors of sound production and incorporate them back into the music.

In music, tone is distinct and identifiable, and when played correctly and in harmony within an ensemble, it sets the overall mood and quality of a performance. However, mastering tone does not come easily. It requires hard work and a dedication to good musical habits, which come from a well-balanced “daily diet” of exercises, according to Jarrett Lipman, director of bands at Claudia Taylor Johnson High School in San Antonio.

Dr. Kirk Moss‘ high school ensembles received significant recognition for their beautiful tone. “One of the reasons I moved into higher education was to share how I was getting that sound with a broader population,” he says.

Through various steppingstones — including becoming a strings teacher — Moss is now chair of the Department of Music and Theatre at the University of Northwestern in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Both Lipman and Moss share tips on how wind and strings students can perfect their tone.

For Brass and Woodwinds

Breath Support: For good tone on wind instruments, Lipman tells his students to “breathe to play, not breathe to live.” Distinguishing “between a breath we might take walking around during the day versus the proper breath to play [an instrument]” can make a big difference in tone quality, says Lipman, who was on the brass staff for the Boston Crusaders Drum and Bugle Corps.

He recommends practicing breath support during sectionals because technique may vary depending on the instrument. For example, an oboe player wouldn’t need to “fill up” the same way as a tuba player, he says.

Embouchure and Posture: After breath support, students need to work on embouchure, tongue placement and posture. “We’re constantly monitoring their physical habits,” Lipman says.

He compares developing good musical habits to having a healthy, well-balanced diet. “We talk a lot with the winds players [about a] daily diet or daily drill,” he says. “For brass, you want whole-note scales [and] Remington exercises. For woodwinds, we try to do an interval exercise.”

To keep students practicing good tonguing and embouchure skills, Lipman recommends incorporating these exercises into the warmup music. “Nothing exists in a vacuum,” he says. “We always want our fundamentals exercises to directly apply to our music.”

For Strings

Focus on the Bow: According to Moss, the greatest factor affecting tone in a stringed instrument is how a player handles the bow. Bow use is one of the most important “variables of sound, whether we’re dealing with beginners or advanced artists,” he says.

Many facets of the bow work together to produce sound, and a change in any of those variables results in a change in tone. “The bow is a huge and often underestimated tool in the musician’s hand,” Moss says. “It makes more of a difference than the instrument or the strings themselves.”

Factors to consider include the placement of the bow relative to the bridge and fingerboard, the weight of the bow on the strings and the speed of the bow. “That can include the tilt of the stick, how the hair contacts the string and, finally, the direction — whether it’s a down bow or an up bow,” Moss says. “Those variables … dictate the tone that students are going to produce.”

Work on Both Hands: Moss explains that musicians often neglect their bow skills because “so many of the materials available for school programs [are] left-hand driven,” meaning that they focus on students’ finger skills with the fingerboard. That’s why Moss co-wrote several exercise books — including Sound Innovations for String Orchestra: Creative Warm-Ups and Sound Innovations for String Orchestra: Sound Development — that feature sections on bowing.

Strings students need to hone skills in both their right and left hands to gain a well-rounded string education. “It’s important to choose resources that teach the right hand beyond how to hold the bow,” Moss says. “Holding the bow is an important step, but it doesn’t end there.”

Moss recommends that educators work with students to develop finger flexibility in both hands. “It really comes down to treating the right hand [and the bow] as a separate instrument,” he says. “Once those right-hand fingers are flexible, [it] opens up all kinds of sound.”

For Everyone

Prioritize Daily Tone Practice: Regardless of what instrument you play, practice is necessary to master tone. Lipman recommends that educators break down their rehearsal time to allow for tone exercises. “If you have a 45-minute rehearsal, take 10 to 15 minutes [to] build their ensemble skills; [treat] it like a masterclass on tone quality,” he says.

This masterclass mindset is important, so students don’t treat the exercises like a warmup that they can later ignore. “A lot of times, when you do a B-flat scale to warm up, it becomes, ‘I played my B-flat scale to get to the music,'” Lipman says.

Listen to Great Music: According to Lipman, mastering tone comes down to the fundamental understanding of what good sound is and what the instrument is meant to sound like. “Listen to recordings, listen to symphony orchestras,” he says. “The hardest part is when you don’t know what you’re working toward. It’s important [that] you find something you really like and find [out] how they do it.”

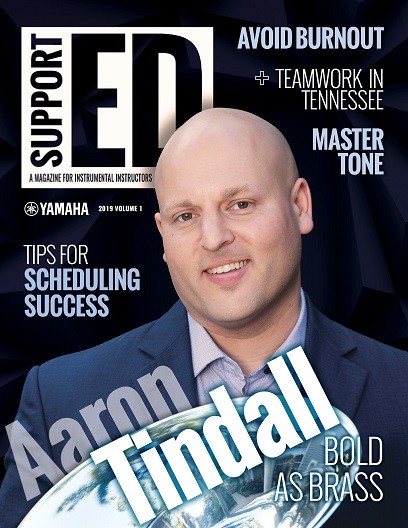

This article originally appeared in the 2019 V1 issue of Yamaha SupportED. To see more back issues, find out about Yamaha resources for music educators, or sign up to be notified when the next issue is available, click here.