Moonlanding: The Soundtrack to an Era

Look up into the skies and dream whatever you want to dream.

On his 1967 album Axis: Bold As Love, Jimi Hendrix wondered what would happen “if 6 turned out to be 9.” The mystical implications of those digits (both are multiples of the magic number 3) would not have been lost on Hendrix, but he was also pondering the upside-down quality of that time and envisioning what might happen by the year that would, at least symbolically, end the era that had already become known as “The Sixties.”

By the time 1969 arrived, it was pretty evident that whatever utopian hopes the Sixties generated were unlikely to be realized. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy had been assassinated within two months of each other in 1968. The Democratic National Convention in August of that year had turned into a pitched battle between the Chicago police and antiwar protesters. Richard Nixon had been elected president in November of 1968 and was inaugurated the following January. He had run on a “law and order” platform that served as the template for many of the culture clashes that still rage today. The conservative Silent Majority were pitted against young counterculture insurgents who viewed themselves, in the words of the Jefferson Airplane, as “outlaws in the eyes of America.”

I was one of those kids. Growing up in Greenwich Village within walking distance of the Bitter End, the Café Au Go Go, the Fillmore East and a dozen great record stores, I was obsessed with rock & roll. I listened to it (and read about it) constantly. By the summer of ’69, I had seen the Rolling Stones, the Who, the Jefferson Airplane, Traffic, Jimi Hendrix, the Doors, B.B. King, Joni Mitchell and too many other artists to count. I was ravenous for it; music gave my life meaning. I was also draft age, unfortunately. I turned 18 less than a month before Apollo 11 blasted off into space, with the Vietnam War going full force. I was about to attend college but sensed that those deferments would soon end. It was a heady time, with more transporting music than I ever could have dreamed of, but there was a tense underpinning to it all.

During his campaign, Nixon promised that he had a “secret plan” to end the hostilities. That plan turned out to be so secret as to be nonexistent. The war dragged on, with more than five hundred thousand American troops facing enemy fire in a country smaller than California, suffering tens of thousands of deaths and casualties. Yet ironically the music our soldiers were listening to were the songs of the very artists — Hendrix, the Doors, Marvin Gaye, Creedence Clearwater Revival, the Temptations — who were creating a soundtrack of rebellion and escape. Whenever anyone mentions the great divisions of our own times, I think back to those days fifty years ago. For better or worse, the parallels are chilling.

Still, a few points of unity stirred back then and the ideal of space travel was one of them. It wasn’t entirely untainted, alas. By 1969, any major project the US government undertook became suspect for its potential military or surveillance applications. Nonetheless, the sheer vastness of space, not to mention our shared status as human beings on a planet floating in a mysterious universe, made it possible for anyone to look up into the skies and see what they wanted to see, dream what they wanted to dream. They are called “the heavens” for good reason. Whatever your politics, whichever side you were on, you had reason to want to go there.

Once President John F. Kennedy declared in 1961 that America would land a man on the moon before the end of the decade, space themes began weaving their way into popular culture — TV in particular. “Star Trek” debuted in 1966 and rested on the premise that space was the “final frontier,” vowing to take viewers “where no man has gone before.” In “I Dream of Jeannie,” space travel joined with romance as an astronaut stranded on a remote island discovered a lovely genie in a bottle. “The Jetsons” imagined a space-age future just as “The Flintstones” captured how the glossy future just around the corner made our lumbering, sub-lunar world seem like the Stone Age.

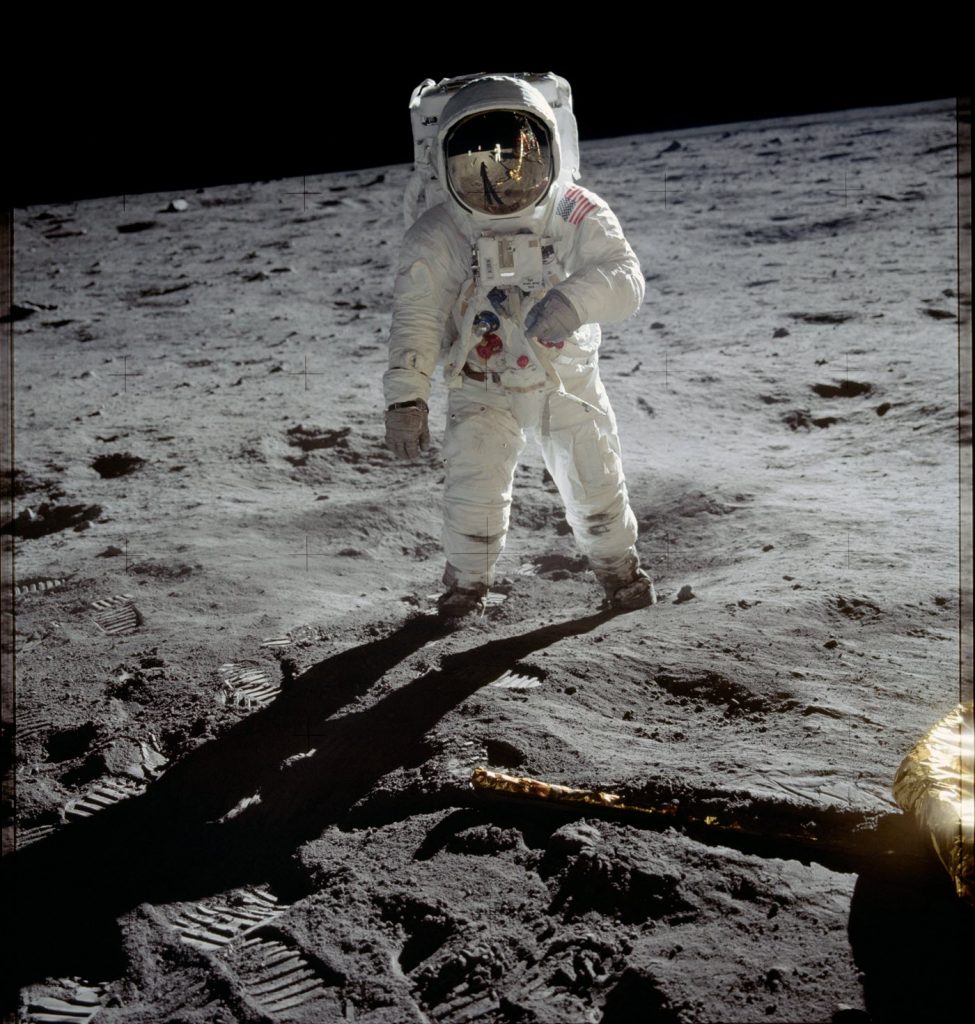

As always, music was at the center of everything. All those shows had theme songs that seemed ubiquitous, and the moon retained the power it has always held as a symbol of romance. Indeed, Frank Sinatra’s exuberant version of Bart Howard’s “Fly Me to the Moon” became the first song played on the moon when astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin gave it a spin on a portable tape player after the Apollo 11 landing. Yet popular culture, characteristically, found ways to capture some of the fears — and some of the cultural ambivalence — that countered the triumphs of the Apollo missions. Even an elegant pop ballad like Jonathan King’s “Everyone’s Gone to the Moon,” a Top 20 hit in 1965 (and another song listened to by the Apollo 11 crew during their flight), treated the moon as a source of alienation. And David Bowie’s “Space Oddity,” released the week before the Apollo 11 launch, imagined a technological breakdown resulting in Major Tom’s being forever lost in space. That song was inspired by Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, which made brilliant use of classical pieces like “The Blue Danube” and Also Sprach Zarathustra, but also envisioned a future in which the very technology that made space travel possible would put human life at risk.

Of course, the actual moonlanding itself couldn’t have been more inspiring. I watched it with my mother in our family’s apartment and even as a teenager the implications of it loomed large for me. It seemed much more than a purely American achievement of “one small step for man”; indeed, it was truly “one giant leap for mankind.” It suggested that there was nothing our shared human vision couldn’t engage and accomplish. The question arises at every moment of social convulsion: “Can’t we all just get along?” In July of 1969, the resounding answer was yes.

But whatever was happening on the moon, the realities of life on Earth could only be held at bay so long. Just weeks after the moonlanding, the Tate-LaBianca murders in Los Angeles chilled the heart of a community that had been one of the hotbeds of Sixties musical and cinematic creativity. In contrast, less than two weeks after that, the Woodstock Festival offered a prospect of peace and love. By the end of the year, however, the mayhem and murder at the Rolling Stones’ concert at the Altamont Speedway in California eviscerated the hippie dream.

Events moved at a strange pace in the Sixties, simultaneously fast and slow. So much happened in such close proximity, but, as George Harrison once described to me about that era, “you could say any year from 1965 up to the Seventies, it was like … those years seemed to be a thousand years long. Time just got elongated. Sometimes I felt like I was a thousand years old.” So that first moonlanding was both a monumental event in human history and just another milestone that got immediately swept up in the head-spinning tumult of the times.

Space travel soon receded as an American priority, but as the psychedelic music that accompanied the dawn of the space age suggested, profound journeys don’t always head outwards. Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, for example, charted for more than 2 1/2 years following its initial release in 1973, and continued to chart on a regular basis until 1988. To this day, it remains an essential experience for any young person exploring the wonders of classic rock — and the search for personal identity.

When I think about space travel myself, I often conjure up the extraordinary “Blue Marble” photograph of the Earth taken by the crew of Apollo 17 (the final Apollo flight) on their way to the moon in 1972. There is our planet, our shared home, so beautiful and exhilarating to see. The true meaning of all we had accomplished came clear to me when I saw that image. From outer space, we could achieve a previously impossible perspective on our own world, an appreciation for the life we know that would lend real meaning to even our farthest flung explorations. “If you know what life is worth / You will look for yours on Earth,” Bob Marley sang in 1973. The heavens, then, might prove a good deal closer than we could have believed.