Tagged Under:

Fix It: Snare Drum Rolls Teaching Tips

Try these expert tips on fixing common errors students make when performing snare drum rolls.

Close your eyes for a moment and imagine a time when you were conducting on the podium and cued a much anticipated, exposed and important snare drum roll. What did it sound like?

Perhaps it was smooth, expressive and confident — maybe the result of assigning your best snare drummer to the part. Or perhaps it was choppy, crushed or uneven, leaving your student deflated or even unaware of what a good roll should sound like.

The goal of this article is simple: To help your students become more confident playing buzz/multiple bounce/concert rolls on snare drum. While this goal might sound simple, it certainly is not easy because mastering the snare drum roll is a lifelong quest for even the most seasoned professionals.

One of the things that makes the snare drum and snare drummers special is the capacity and responsibility to lead. Whether laying down a powerful backbeat on drum set, executing a delicate passage in orchestra or cleaning a showstopping feature in drumline, the snare drum acts as the “nucleus” of percussion — the center from which everything else derives.

One of the things that makes the snare drum and snare drummers special is the capacity and responsibility to lead. Whether laying down a powerful backbeat on drum set, executing a delicate passage in orchestra or cleaning a showstopping feature in drumline, the snare drum acts as the “nucleus” of percussion — the center from which everything else derives.

So much of what our students learn from snare drum study — technique, tone, touch, control, speed, rudiments and reading skills — can be applied to other percussion instruments. This is called “transfer value.” For example, matched grip snare drum technique and hand motion, with slight modifications, can be applied to two-mallet keyboard, multi-percussion, drum set, timpani, steelpan, marching tenors and bass drum, concert bass drum, suspended cymbal, temple blocks, castanets, congas, djembe, cajon and others.

Download this Yamaha Drums and Percussion Care Checklist for Students now!

As we know, rolls are a percussionist’s way of sustaining sound on snare drum. In my experience, students struggle with playing good rolls because of four common problems. As you work with your students to address these problems, their confidence will grow and their rolls will improve, even before the sticks touch the drumhead.

| READ: Enhance Snare Drum Performance with Instrument Selection, Preparation and Tuning |

Fix It: Unclear Concept of Sound

The first problem students encounter is that they simply don’t know what a good roll is supposed to sound like. They don’t have a concept of sound in their minds and ears. I learned this concept from Gary Cook, my professor at the University of Arizona. He gave cymbal clinics and emphasized that to play cymbals well and execute a good crash, you first had to know what a good crash sounded like. You had to have a concept of sound in your mind. He encouraged us to listen to recordings of great orchestral cymbal players, attend live concerts and record ourselves in the practice room. Over time, we developed our “ear chops” and awareness for what a quality cymbal crash sounded and felt like. We had an ideal standard and a goal to strive for.

The same process can be applied to rolls. Encourage your students to listen to recordings, watch videos, record themselves and attend concerts by professional symphony orchestras, wind ensembles, concert bands, percussion ensembles and percussion soloists. Encourage them to take private lessons and watch and listen to their teacher demonstrate and model an excellent snare drum roll.

One resource I use and recommend for developing a concept of sound on snare drum is Rob Knopper’s Delécluse: Douze Études for Snare Drum. In 2014, Knopper, a percussionist for New York’s Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, recorded all 12 of the Delécluse Études for the orchestra’s 50th anniversary and interviewed Delécluse before he passed away in 2015. Although these etudes are advanced, they provide wonderful input for listening and developing a concept of sound.

By listening to a variety of orchestral/concert snare drummers, both past and present, your students will become more confident knowing what a great snare drum roll sounds like, leading directly to a higher standard and expectation of what they are working toward.

| READ: Pick the Right Drumsticks and Mallets |

Fix It: Unnecessary Tension

Another issue that is common among young players, especially when they roll, is unnecessary tension. Tension can appear in the hands, wrists, arms and shoulders, or even the back, neck and face. Tension in these areas grow without trust in one’s technique. Too much tension when playing rolls will lead to a choppy, crushed and uneven sound.

One of the best mindsets I have come across for staying relaxed and alleviating tension is “letting the sticks do the work.” To use our cymbal analogy again, this is the mindset I use to teach crash cymbals by letting the cymbals do the work. Young cymbal players tend to overplay, opting for an excessive, forceful or aggressive approach.

Another analogy I use is the “bird grip,” borrowed from legendary jazz drummer, Jim Chapin, who was a student of Gus Moeller, creator of the Moeller Technique. The technique develops relaxed movement, flow and efficiency when drumming. In the instructional video, “Speed, Power, Control, Endurance,” Chapin says of the grip, “Think about holding a fledgling bird in your hand, a bird that would escape if it flies or moves around too much, but you don’t want to hurt it.”

To improve your students’ confidence as well as the quality of their rolls, start by introducing them to these two concepts — letting the sticks do the work and the bird grip. Then, give them a fundamental buzz exercise like Four or Eight on a Hand.

In the video, “4 Steps to Build a Smooth Buzz Roll,” Knopper says, “Step one is to work on the individual buzzes [and] start focusing into the quality of the buzzes.”

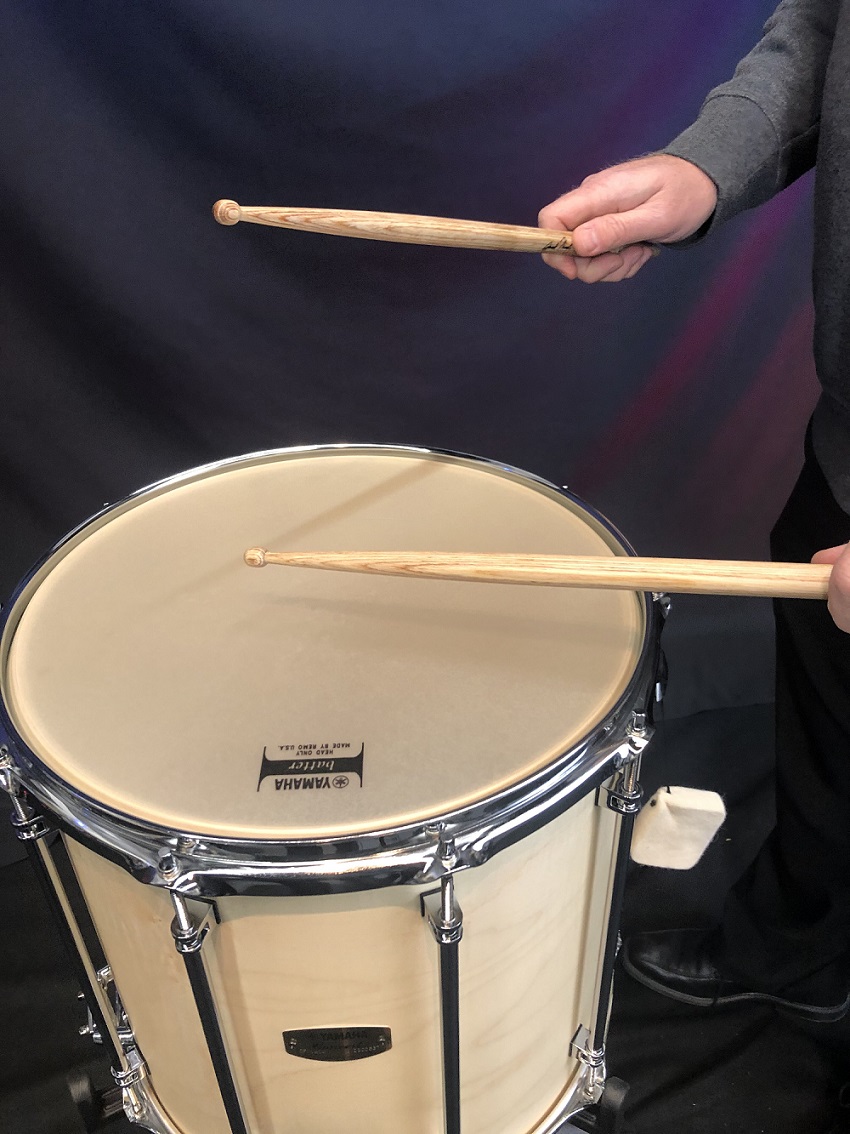

For young players, start with one hand at a time by dropping the stick on the head, allowing it to bounce multiple times. Use the arm to provide weight behind the dropping motion, rather than using the wrist (more about arm in “Unused Arms” below). Keep the dynamic level at a mezzo forte or softer for now. With a comfortable and secure fulcrum, experiment with your grip using a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being the most relaxed.

Remember to let the sticks do the work and try to get as many bounces as possible from each hand. As you practice, be aware of density (how many bounces) and shape (volume consistency of bounces) with each stroke.

Going back to the video, Knopper says, “Step two is to make sure your right hand buzzes and your left hand buzzes sound the same.”

He goes on to say that “step three is the transition from right to left and left to right. You want it to be seamless so you can’t tell when one buzz stops and the other starts. …Work on right to left and repeat it, and work on left to right and repeat it.”

Step four is “building it back into the roll,” Knopper says.

After practicing single-handed buzzes, start alternating and overlapping two buzzes (RL), three buzzes (RLR), four buzzes (RLRL), etc. until a smooth slow roll is achieved.

| READ: Anatomy of a Snare Drum |

Fix It: Unused Arms

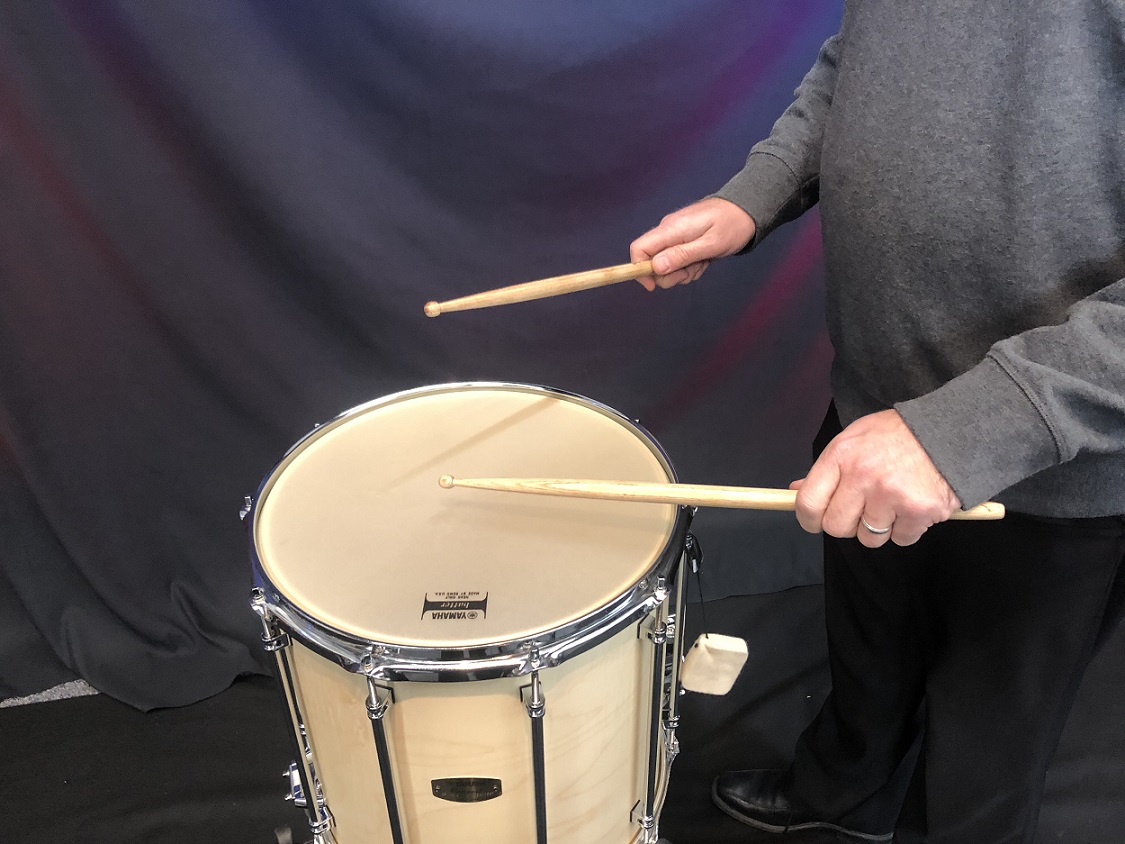

Another issue young players run into when playing rolls is using their wrists instead of their arms. Without question, this idea is counterintuitive, as the majority of snare drum technique involves the wrist as the primary “lever.” By moving the sticks up and down with the wrists, they become perpendicular to the drumhead, allowing them to rebound when playing full/legato/rebound/free/piston strokes. In contrast, using the arm as the primary lever keeps the sticks flatter, lower and more parallel to the drumhead, allowing them to strike the head at an angle more conducive to multiple bounces. Because the arms are a larger muscle group than the wrists, their additional weight will improve stamina, power and endurance, especially for loud and fast rolls. According to St. Louis Symphony Orchestra principal percussionist Will James in his book, “The Modern Concert Snare Drum Roll.”

Using the arm to create the roll stroke is probably the hardest aspect of the concert roll to understand because for years we have been taught that the wrist controls the snare drum stroke. This is absolutely true for individual, single strokes! However, when multiple strokes are desired, the wrist becomes much less effective and efficient. Many players suffer from tendinitis and sore wrists and hands. A large part of their pain can be traced back to abuse of their wrists by trying to execute a snare drum roll using the wrists as the catalyst…The stroke to create a single stroke and the stroke to create a multiple bounce stroke are entirely different because the energy needed to create a multiple bounce stroke is significantly greater.

The best analogy I have found for using the arms when rolling is called “The Chicken Wing Technique” by Ted Atkatz, former principal percussionist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. The idea behind the Chicken Wing is to use your arms, elbows and even shoulders in a way that mimics a chicken flapping its wings. This arm motion becomes the primary lever and allows the player to relax and avoid tension and fatigue resulting from playing primarily with the wrist.

In his book, “The Regimen,” Shaun Tilburg, principal percussionist of the Phoenix Symphony Orchestra, writes, “Rely heavily on your arm for the stroke, minimizing any wrist break. This will facilitate consistency as well as tension free speed.” This technique has served me well playing rolls at all dynamics and tempos and has become my default approach.

Fix It: Undefined Roll Bases

The final problem that can affect a young player’s confidence playing rolls is not having a grasp of roll bases. Roll bases are also known as “skeleton rhythms” and refer to the underlying rhythm or “skeleton” within a roll. The skeleton is similar to a check pattern, where a basic rhythm is played first before anything else like flams, diddles or, in this case, buzzes are added.

For rolls to begin and end in time and sound smooth, expressive and confident, students must decide on a roll base. A good question to ask is, “What roll base will sound best given the tempo and dynamics of the music?” The two most common roll bases are 16th note and triplet bases. One of the two will usually work, depending on the tempo and dynamics called for. However, odd roll bases such as 5s and 7s are also good options, especially for more advanced players in order to “balance the hands” and remove any strong-hand dominant pulses in the roll.

In his book, “Dr. Throwdown’s Rudimental Remedies,” John Wooton, professor of percussion at the University of Southern Mississippi, writes, “Try to end on the opposite hand that you start with when playing orchestral rolls. This gives the illusion of no pulsation because it is hard for the listener to detect the odd number.”

In general, the softer you play, the slower your roll base and the more bounces you need per hand. The louder you play, the faster your roll base and the fewer bounces you need per hand. Check out some examples from the video “Shaun Tilburg’s Regimen: Fundamental Roll Techniques.”

One of the most effective strategies I have found to develop my skills as a percussionist is to practice slowly. In fact, a quote I share with all my students is: “Slow practice equals fast progress. Fast practice equals slow progress. No practice equals no progress.” Snare drum rolls especially benefit from and respond to slow practice because it’s easy to “hide” buzz quality and length when rolling fast.

The Best Roll Exercise

Hands down, the best roll exercise I have come across in my 25+ years of teaching percussion was published in the Percussive Arts Society digital publication Rhythm! Scene (which is now PAS’ official blog). The exercise, “The Silky Smooth Soft Roll” by Phillip O’Banion, director of percussion studies at Temple University, takes you through half note, quarter note, eighth note, triplet, 16th note and quintuple roll bases at a soft dynamic level.

To me, “Silky Smooth” is pure gold because it works and allows me to focus on my concept of sound, unnecessary tension, the Chicken Wing technique and roll bases separately as well as together.

Advice for Music Educators

Many years ago, I attended the National Conference on Percussion Pedagogy and heard a quote by Dr. Dennis Fisher from the University of North Texas that changed how I play and teach. He said “40% of the music is written down, 60% is not.”

When I share this quote with my students, I hold up a printed part and tell them, “This isn’t music. This is just a piece of paper with black notes on it. Music is what comes out of your instrument, and more importantly, what comes out of you as a player.”

I then ask them what 40% will earn them on a test or assignment and watch the dots connect. Uncovering and discovering more of the 60% — the music that is not written down — is their new job.

What is the 60%? Phrasing, dynamics, touch, expression, musicianship, interpretation and sound quality — all attributes that go beyond just playing the right notes and rhythms.

It is important to communicate to your students that it is okay to go beyond playing the notes in front of them, sometimes referred to as “playing the ink.” After all, learning the notes is the first step, not the last. While many young players might think they are “finished” when they learn the part on the page (the 40%), this is only the starting point.

The 40-60 mindset can be applied to any instrument, piece of music or technique, including snare drum rolls. By addressing an unclear concept of sound, unnecessary tension, unused arms and undefined roll bases, your students’ confidence will begin to soar, but only with practice.

“Prove to your hands that you’re serious,” I tell them. “If you want to improve, you have to practice consistently. Aim for 6 days a week, with one day off to rest, recharge and recover, like an athlete.”

To inspire your students, ask them to prove to their hands that they’re serious by earning the confidence that inevitably comes from commitment, sacrifice and preparation. And the next time you are conducting and cue a snare drum roll, trust their technique and aim for the 60%!

References

- Atkatz, Ted. “The Chicken Wing Technique.” Vic Firth Fundamentals 2. vicfirth.com. 2009.

- Buyer, Paul. “Drumline Gold.” Meredith Music Publications. 2020.

- James, Will. “The Modern Concert Snare Drum Roll.” Meredith Music Publications. 2014.

- Knopper, Rob. Delécluse: Douze Études for Snare Drum. 2014.

- Knopper, Rob. “4 Steps to Build a Buzz Roll.” robknopper.com. 2016.

- O’Banion, Phillip. “The Silky Smooth Soft Roll.” Rhythm! Scene. February 2018.

- Tilburg, Shaun. “The Regimen: Fundamental Roll Techniques.” vicfirth.com. 2017.

- Tilburg, Shawn. “The Regimen.” Self-published. 2015.

- Wooton, John. “Dr. Throwdown’s Rudimental Remedies.” Row-Loff Productions. 2010.